Daguerreotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856.

Daguerreotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856.

Photograph by Benjamin D. Maxham, 1856.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 28 April 2022. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Henry David Thoreau wanted to be a writer, and he loved the woods. In 1845, he moved to the shores of Walden Pond, about a mile from Concord, Massachusetts. There, with a borrowed axe and the help of friends, he built a small house, where he lived for two years. It was an “experiment,” he wrote. Walden, the famous book that described it, was his account of the results.

The book has played an outsized role in the history of environmental thought and politics, and the place where the experiment unfolded has become a site of pilgrimage for Thoreau’s fans. As Lawrence Buell describes in The Environmental Imagination, “Concord, Massachusetts is America’s most sacred literary place.” And as the local historian Leslie Perrin Wilson notes in The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism, pilgrims to Walden Pond “invest it with the capacity to spark their own spirituality, insight, and creative energy, as it did Thoreau’s.” The site where Thoreau went to live and write continues to attract visitors who take inspiration from his vision of life integrated with nature.

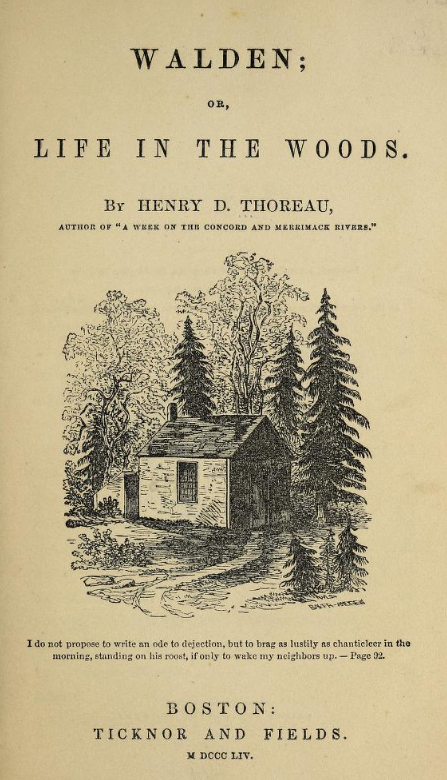

Wood engraving, title page taken from the first edition of Walden, 1854.

Wood engraving, title page taken from the first edition of Walden, 1854.

Engraving by Baker-Andrew after a sketch by Sophia Thoreau (1819–1876), 1854.

Accessed via the Archive.org, 28 April 2022. .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

But the stories we tell about Walden Woods are often incomplete as scholars in the environmental humanities have argued. Emily O’Gorman and Andrea Gaynor’s article “More-Than-Human Histories” suggests that approaches often described as multispecies or more-than-human can enrich ongoing studies in environmental history. Such approaches—developed by scholars like Donna Haraway, Jane Bennett, and Anna Tsing among many others—can rectify intransigent binaries between nature and culture in environmental history. Such scholars have worked to describe alternative ontologies and epistemologies—which is to say, views of what is and how we know it—that are premised on human embeddedness in relational networks.

Thoreau’s Walden Woods may seem an unlikely candidate for this kind of treatment.

Walden Woods of 1845 appears in the popular imagination as a kind of “wilderness,” and Thoreau’s writings contribute to this image through their emphasis on solitude. When William Cronon argued, in 1995, that there was “trouble with wilderness,” he began the article wondering whether Thoreau’s description of “wildness” as the “preservation of the world” was a good idea. The article expressed good reasons to doubt the concept. Wilderness in America, Cronon wrote, was the inheritance of European religion, a value held by city-folk who wanted to escape, a romantic longing for the frontier, and “the last bastion of rugged individualism.” Wilderness was a concept that had not preserved the worlds of North America’s first nations: In fact, it had facilitated their dispossession. Before America’s national parks could be “uninhabited,” their inhabitants had to be “rounded up and moved onto reservations.” All of this suggested that wilderness as a framing device for environmentalism and the dualism between nature and culture that it represented was a mistake. Cronon redeemed Thoreau in the end, distinguishing Thoreau’s “wildness” from the settler imagination of “wilderness,” but others have, understandably, not been so optimistic. Thoreau has been rendered in many of our imaginations as the paragon of a disconnected individualism, the opposite of the relational vision that multispecies studies has aimed to cultivate.

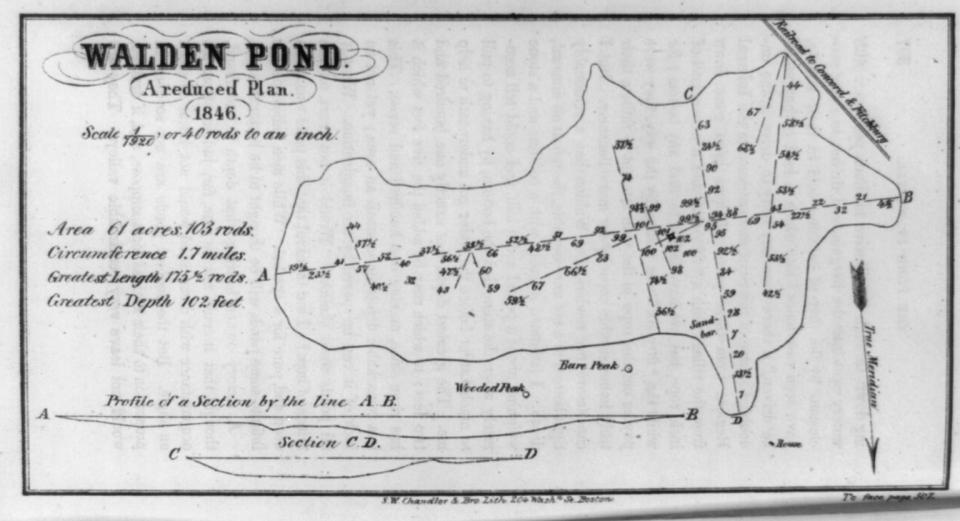

Lithograph plan of Walden Pond, 1846.

Lithograph plan of Walden Pond, 1846.

Lithograph by S.W. Chandler & Bro., 1846.

Accessed via the Library of Congress on 28 April 2022. Click here to view source.

But what happens when we look at Walden Woods of 1845 with a multispecies frame of mind?

There is another way to tell the history of Walden Woods. When we read about Thoreau’s experiment with multispecies approaches in mind, and an appreciation for his indebtedness to religious, ascetic practice, we can discover a whole community occupying the woods alongside him, plants and creatures and workers and former inhabitants (some of them who had once been enslaved people) who were all there, with Thoreau, occupying the woods. When read in this light, Thoreau’s own writings describe Walden Woods as a vividly populated community, its own kind of monastery. Thoreau writes poignantly in his Journal, for example, about a day in 1845 when he was chatting with a new friend, a French woodchopper named Alek Therien, who worked in the woods. Together, they encounter a bird and share a caring mutual curiosity about one another’s languages: “What do you call them?” they ask one another, trading the French and English words for chickadee.

Just then one flew up from the snow and perched on the wood I was holding in my arms and pecked it and looked me familiarly in the face. Chica-a-dee–dee-dee-dee-dee,—while others were whistling phebe,—phe-bee,—in the woods behind the house.

Thoreau’s writings record for us the voice of the chickadee who lived with him in the woods, and yet, too often, we have emptied the woods of their inhabitants. When Thoreau lived there, “Regularly at half past seven, in one part of the summer, after the evening train had gone by, the whippoorwills chanted their vespers for half an hour, sitting on a stump by my door” (Walden). In this way, we might see the book itself as cocreated within multispecies relationships, arising out of a conversation among the chickadees and the whippoorwills and the workers, among other members of the Walden Woods society that I describe in my recent book, Thoreau’s Religion.

Photograph of Walden Pond, 1900–1910.

Photograph of Walden Pond, 1900–1910.

Unknown photographer, 1900–1910. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Pointing out Thoreau’s multispecies relationships can also help us to reimagine his religiosity. A turn to religion has been under way in the study of Transcendentalism since the mid-1990s, but in-depth studies of Thoreau’s religion are rare. Alan Hodder’s Thoreau’s Ecstatic Witness is one of the best. But Hodder sometimes succumbs to a common habit in the study of mysticism, which is to represent the spiritual practitioner as a kind of solitary spiritual genius. (Hodder: “Religion was for him essentially a private concern.”) When we acknowledge the multispecies community that Thoreau joined in the woods, we gain a truer, more relational picture of the religion he practiced there. This, in turn, shows us that Thoreau’s religion was more closely allied to his politics than readers usually recognize.

Thoreau’s perhaps unexpected amenability to recent trends in multispecies studies is no accident. Thoreau himself wrote about the fact that we are “a part and parcel of nature.” And major figures in the movement, such as Jane Bennett, have written under the influence of their study of his writings. All of this suggests that O’Gorman and Gaynor are right—environmental histories through a multispecies lens can reinvigorate our understanding even of some of the most familiar evidence. Thoreau’s Walden Woods of 1845 were as full of the sacred as the pilgrims who visit them now hope they will be.

How to cite

Balthrop-Lewis, Alda. “Multispecies Walden Woods: Reevaluating Thoreau’s Religion.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2022), no. 7. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9406.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Alda Balthrop-Lewis

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Bennett, Jane. Thoreau’s Nature: Ethics, Politics, and the Wild. Revised edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

- Buell, Lawrence. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996.

- Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–28. doi:10.2307/3985059

- Finley, James S., ed. Henry David Thoreau in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Hodder, Alan. Thoreau’s Ecstatic Witness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Myerson, Joel, Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, and Laura Dassow Walls, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- O’Gorman, Emily, and Andrea Gaynor. “More-Than-Human Histories.” Environmental History 25, no. 4 (October 2020): 711–735. doi:10.1093/envhis/emaa027.