In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King, Jr. declared: “No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.” The image of power that he chose comes from the natural world of rivers, the mighty streams whose unstoppable force guarantees that justice will ultimately prevail over inequality. The civil rights leader and Baptist minister was referring to the Bible passage in which the prophet Amos calls for a conversion of his people (Amos 5:24). Our current ecological crises may not necessitate such a religious interpretation, but they do require a massive shift in mentality and outlook on the natural world. One of the elements that is undergoing reconsideration in environmental discourse is water, especially rivers and flowing streams.

Banks of the Rhine river flooded in Cologne in 2021.

Banks of the Rhine river flooded in Cologne in 2021.

Photo by Raimond Spekking, 2021. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The ancient image of rivers as powerful entities is not immediately obvious to modern humans: Most urban inhabitants see a river as a passive backdrop to their activities, not a mighty creature with a life of its own. However, recent flash floods in many parts of the world (including in Germany in 2021) have reminded many of the power of rivers and the importance of fluvial ecosystems (fig. 1). Current ecological crises call for a serious reconsideration of our relationship to rivers. Several countries (Ecuador, Columbia, New Zealand, and India) have responded to this challenge by granting rivers the legal status of persons. As Catherine Iorns shows, legislation was grounded in native traditions that regard rivers as living creatures. Similar concepts appear in many ancient cultures that regard rivers as nonhuman beings. The ancient conceptions of rivers as more-than-human agents can serve as an illuminating way to stimulate the current debate on rivers and fluvial environments. This paper shows that ancient rivers were often depicted struggling with human heroes, reflecting the human desire for mastery over the environment.

A river was not always perceived as an inanimate mass of water or a static backdrop to human actions. As Emma Aston has argued, rivers were conceptualized in surprising and diverse ways, most often in the shape of nonhuman animals and human-animal hybrids, blurring the conceptual boundary between nature and culture (a distinction that received its definitive form only in the modern period). Greek and Roman river gods often had the attributes of bulls, snakes, and horses, along with supernatural qualities.

The most salient example appears in Homer’s Iliad, Book 21. The Trojan river Scamander (or Xanthus, meaning “yellow,” reflecting the colour of sandy water; today called Karamenderes River) has both human agency and divine power. The powerful stream, conceived as a bull, fights the Greek hero Achilles and almost kills him. The episode occurs after the raging hero Achilles, angry because of the death of his friend Patroclus, kills so many Trojans that their bodies clog up the river Scamander and its waters run red with blood. In order to prevent more killing and the pollution of its waters, Scamander responds with a threat to Achilles: He will cover the hero’s body deep down under its waves with sand and rubble. The raging current of the river rises and drives against Achilles so that he can barely stand. The greatest of Greek heroes at Troy then “sprang from the whirlpool, and darted fleeing swiftly over the plain, gripped by fear” (Iliad 21.246-8, my translation). Achilles repeatedly struggles to escape the clutch of Scamander’s rolling waves and is only saved by the divine intervention of Athena and Poseidon. Thus, in Homer’s vision, the divine river is more powerful than any human hero. The angry Achilles, who put so many Trojans to flight, runs away from the wrath of a divine river.

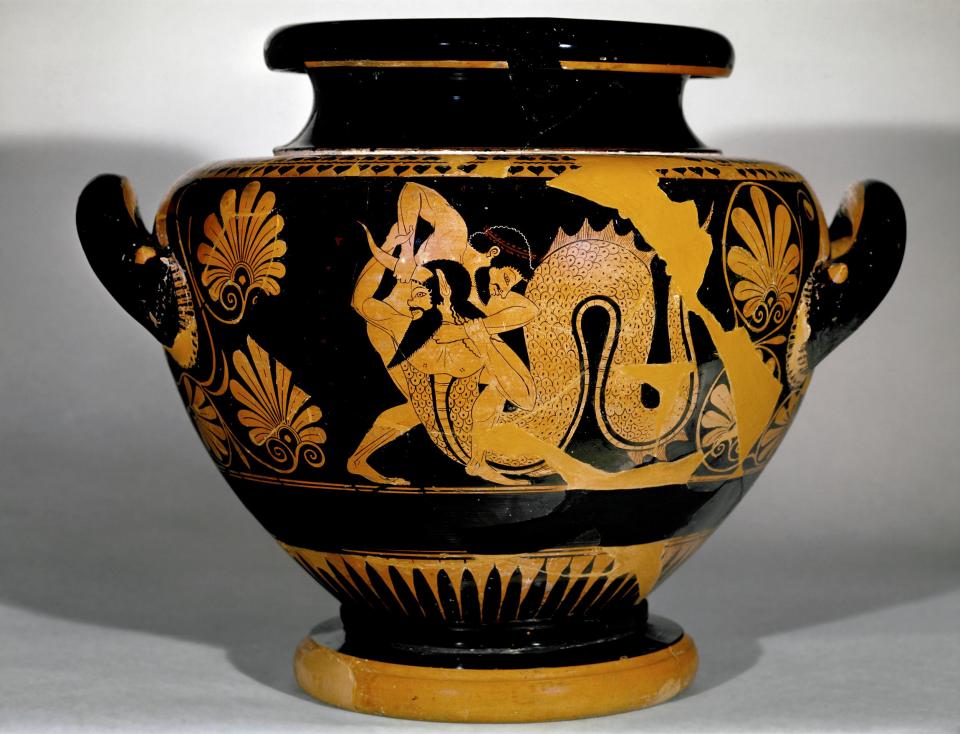

Heracles fighting Achelous.

Heracles fighting Achelous.

Made by Pamphaios (potter)

and Oltos (painter), around 530BC–500BC. Courtesy of the British Museum.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Greek mythology contains many other stories about heroes fighting river gods. In another example, the river Achelous was worshipped as a primordial force, much like the river Ocean, even after Heracles cut off one of his horns in a contest for Deianira, who then became Heracles’s wife (fig. 2). It is interesting to note that in some versions of the myth, the horn becomes a source of abundance (Latin cornu copiae), full of fruits and gifts. The struggle not only reflects the continual human desire for mastery over the environment but also demonstrates that the process of conquest is incomplete. No matter how strong the hero, he manages to break only one of the river god’s horns. Moreover, Achelous manages to restore his horn by trading it with Amalthea, the goat that nursed Zeus (Apollodorus’s Library 2.7.5). Thus, the river Achelous is a powerful divinity that bestows plenty but can always restore its destructive force, even after its defeat by Heracles, the son of Zeus.

To sum up, rivers were perceived as powerful divinities in ancient Greece, as we can see in the example of Homer’s Iliad and the myth of Heracles fighting the river Achelous. The two myths indicate a conception of rivers as living agents that humans contended with at their own peril. Their hybrid characteristics blur the boundaries between nature and culture, belying a false dichotomy between humans and the environment. The ancient portrayal of rivers as more-than-human beings is comparable to the conception of rivers as persons in some modern countries and can teach us respect for elements that still defy human control and perception.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

PRIMARY SOURCES

- Apollodorus. The Library. Translated by James George Frazer. 2 vols. London : W. Heinemann, 1921.

- Homer. Ilias. Edited by Martin L. West. Vol 1. Stuttgart and Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter, 1998.

How to cite

Vuković, Krešimir. “The Mighty Streams: Coping with Rivers in the Ancient World.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2022), no. 14. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9529.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Krešimir Vuković

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Aston, Emma. Mixanthrôpoi: Animal-Human Hybrid Deities in Greek Religion. Liège: Presses universitaires de Liège, 2011.

- Currie, Bruno. “Euthymos of Locri: A Case Study in Heroization in the Classical Period.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 122 (November 2002): 24–44. doi:10.2307/3246203.

- Holmes, Brooke. “Situating Scamander: ‘Natureculture’ in the Iliad.” Ramus 44, no. 1–2 (December 2015): 29–51. doi:10.1017/rmu.2015.2.

- Iorns, Catherine. “From Rights to Responsibilities Using Legal Personhood and Guardianship for Rivers.” In ResponsAbility: Law and Governance for Living Well with the Earth, edited by Betsan Martin, Linda Te Aho, and Maria Humphries-Kil, 216–239. London: Routledge, 2019. Victoria University of Wellington Legal Research Papers 11, no. 34 (2021): 1–25. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3270391.

- Schliephake, Christopher. The Environmental Humanities and the Ancient World: Questions and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.