It was a hot day in the middle of July in the year 1551. The king of Kathmandu, Narendra Malla, had reigned for twenty years. The monsoon deluge, vital for Kathmandu Valley’s rice economy, had not come. It was time to appeal to higher powers. A manuscript of an ancient scripture called the Great Cloud (Mahāmeghasūtra) was sent for by the king. The sacred text of the Great Cloud was read aloud by a Buddhist priest from Kathmandu. Its spells would appease the serpents who controlled the celestial waters, the nāgas. The notes made by the manuscript’s owners on its final leaf tell us when and why this ritual took place, and what happened next: the rains came.

Kathmandu Valley’s rice fields in midsummer.

Kathmandu Valley’s rice fields in midsummer.

Photograph by jeeheon, 7 August 2007.

Accessed via Flickr on 2 June 2022. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

While modern climate sciences have paid little attention to rainmaking rituals, records of rainmaking performances offer useful data on climate history. The church and city archives of Europe have long been mined for information on the weather of the past. In the Kathmandu Valley, as well, there are references to rainmaking in manuscripts going back several centuries. Rainmaking was practised from time to time up to the end of the Malla dynasty in 1768. It is still part of the ritual repertoire of the Buddhists of Kathmandu’s indigenous Newar community. However, records of rainmaking performances remain hard to access, in many cases, and the study of Newar historical documents has been moving slowly.

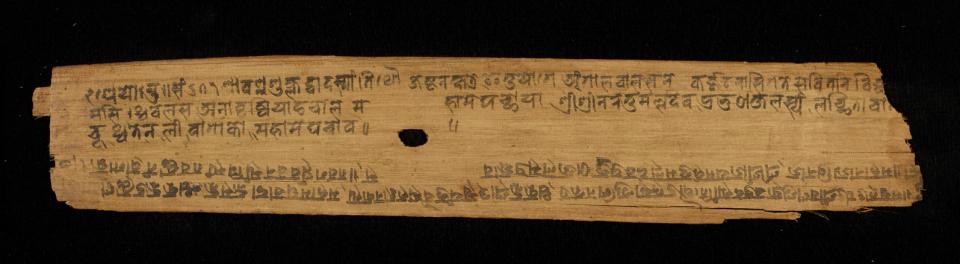

Mahāmeghasūtra, Cambridge University Library MS Or.135.

Mahāmeghasūtra, Cambridge University Library MS Or.135.

Unknown creator, n.d.

Courtesy of Cambridge University Library.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Three more rainmaking efforts are chronicled at the end of the manuscript that records the 1551 ritual. In the summer of 1556, the scripture of the Great Cloud was brought out to be read in response to another drought. Then, a decade later, a new king, Mahendra Malla, was on the throne and the ritual was performed again. This time it was carried out on the sacred hill of Swayambhu. And this time, as in 1551, rain fell.

The choice of Swayambhu as the site for Mahendra Malla’s rainmaking ritual is significant. In the Newar Buddhist worldview, there are deep connections between Kathmandu Valley’s land and water features, the annual monsoon, and the worship of life-giving forces. Long before the Malla period, a drought is believed to have been ended at Swayambhu by a Buddhist master who had travelled from India. He is remembered as “The Pacifier,” Śāntikara, and as the founder of the hill’s famous stupa. His rainmaking efforts were said to have been assisted by the then king of Nepal, Guṇakāmadeva. Their story is narrated in the mythopoetic Buddhist histories of Kathmandu Valley, the Svayambhūpurāṇas, which emerged in the Malla era.

Carved doors portraying Śāntikara (left) and king Guṇakāmadeva (right). Early twentieth century.

Carved doors portraying Śāntikara (left) and king Guṇakāmadeva (right). Early twentieth century.

© 2010 Iain Sinclair. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Successful acts of rainmaking were remembered so that they could be emulated by future generations. A painting of the rainmaking ritual performed by Śāntikara and Guṇakāmadeva was produced in 1635 and is now kept at the Cleveland Museum of Art. It portrays the king dragging the last of the rainmaking serpents to the spot where Śāntikara is making rain. This scene is embedded in an elaborate map of the Valley’s waterways and their resident serpent deities, as described in the Svayambhūpurāṇas. The painting assures viewers that the natural order could be maintained as long as Nepal’s Hindu monarchy and its Buddhist community worked together. In 1658, however, King Pratāpa Malla took matters into his own hands, forcing his way into Śāntikara’s mausoleum to retrieve his precious rainmaking manuscript.

The lore of rainmaking at Swayambhu is now known outside Nepal through the work of scholars such as the late Mary Slusser and, more recently, Alexander von Rospatt. The next steps will be to establish the key rainmaking dates in the historical record, and then, perhaps, to combine them into long-term drought indexes for the Himalayas.

Tantric Buddhist officiants prepare to perform rituals outside Sikwamu monastery (Tarumūlamahāvihāra), Kathmandu.

Tantric Buddhist officiants prepare to perform rituals outside Sikwamu monastery (Tarumūlamahāvihāra), Kathmandu.

© 2007 Iain Sinclair. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The final postscript was added to the Great Cloud manuscript in 1628. This year, the reciter was Bābūdeva, a tantric Buddhist priest from Sikwamu monastery in the Kathmandu royal precinct. Bābūdeva acted at the request of King Lakṣmīnarasiṃha Malla and brought gems to offer at the ritual. The Great Cloud was then recited at another of Kathmandu’s hallowed Buddhist sites: the monastery of Thaṃ Bahī in present-day Thamel district. The sponsors of this recitation seem to have been keen to get a good outcome. The drought must have been severe that year.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the manuscript was acquired in Nepal by the Sanskritist Cecil Bendall (1856–1906). Today the manuscript is kept under shelfmark Or.135 at Cambridge University Library. Thanks to a digitization project at the Library, the Great Cloud manuscript can now be viewed online all over the world. However, the manuscript’s rainmaking records were not transcribed as part of this digitization project, and are being noticed here for the first time.

Before this manuscript left the hands of its custodians, in 1880, Bendall published a study of the Great Cloud based on another, older manuscript. The notes on rainmaking appended to this manuscript, Add.1689, have also gone unnoticed. These records go back to the start of the Malla era, to 1380. They are older than most of the tree ring data collected for studies of the region’s climate. There are more manuscripts of this kind waiting to be studied. For now it is clear that Nepalese documents on rainmaking can contribute to the “cultural turn” in our efforts to understand the relationship between climate and culture in Asia.

How to cite

Sinclair, Iain. “Making Rain under the Mallas.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2022), no. 9. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9417.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Iain Sinclair

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Bendall, Cecil. “Art. X.—The Megha-Sūtra.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 12, no. 2 (1880): 286–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00017512.

- Gaire, Narayan Prasad, Dinesh Raj Bhuju, and Madan Koirala. “Dendrochronological Studies in Nepal: Current Status and Future Prospects.” FUUAST Journal of Biology 3 (2013): 1–9.

- Sieglerschmidt, Jörn. “Complexion and Climate: An Attempt at an Outline of Weather Outlooks in Europe from the Beginnings until Today.” In Climate Change and Cultural Transition in Europe, edited by Claus Leggewie and Franz Mauelshagen, 23–59. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004356825_003.

- Slusser, Mary Shepherd. Nepal Mandala: A Cultural Study of the Kathmandu Valley. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982: 354–59.

- Vargas-O’Bryan, Ivette. “Falling Rain, Reigning Power in Reptilian Affairs: The Balancing of Religion and the Environment.” Religions of South Asia 7, no. 1–3 (2013): 110–25. https://doi.org/10.1558/rosa.v7i1-3.110.

- Von Rospatt, Alexander. “The Mural Paintings of the Svayambhūpurāṇa at the Shrine of Śāntipur, and their Origins with Pratāpa Malla.” In Himalayan Passages: Tibetan and Newar Studies in Honor of Hubert Decleer, edited by Benjamin Bogin and Andrew Quintman, 45–68. Boston: Wisdom, 2014.