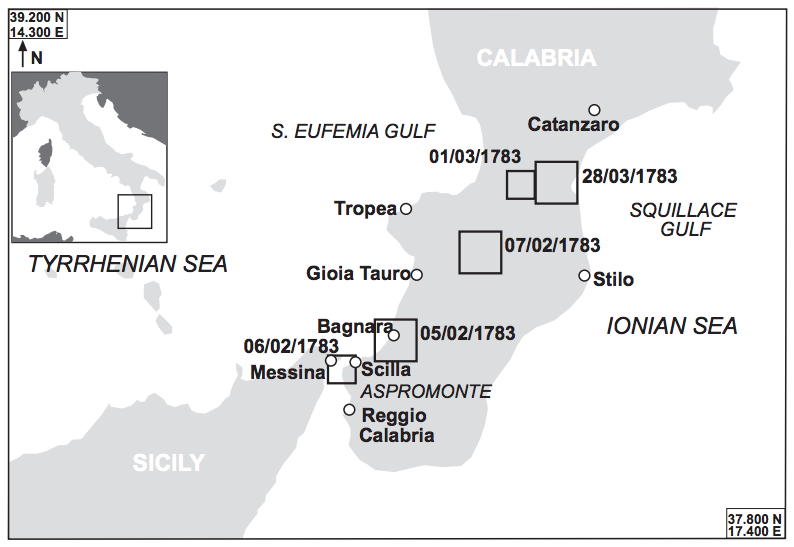

A map of Sicily and Calabria showing the locations of the five main earthquakes of the seismic sequence that shook the region in February and March of 1783.

A map of Sicily and Calabria showing the locations of the five main earthquakes of the seismic sequence that shook the region in February and March of 1783.

Map by L. Graziani , A. Maramai , and S. Tinti.

Originally published in: Graziani, L., A. Maramai, and S. Tinti. “A Revision of the 1783–1784 Calabrian (Southern Italy) Tsunamis.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Science, Copernicus Publication on behalf of the European Geosciences Union 6, no. 6 (2006):1053–1060.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

In an unsual seismic event sequence between 5 February and 28 March 1783, five strong earthquakes shook Calabria and Sicily and were followed by hundreds of aftershocks in the following years. The earthquakes caused ten tsunamis. One earthquake increased the stress on other parts of the fault system and triggered the subsequent earthquakes (Coulomb stress transfer).

The earthquakes caused widespread destruction and killed an estimated 35,000 people. The first and strongest quake of the sequence was the 5 February 1783 earthquake at noon, its epicenter was near Oppido Mamertina. For historical earthquakes not measured by modern seismometers, geologists rely on historical descriptions such as damage reports to estimate their intesity in accordance with the modified Mercalli intensity scale. The strongest possible level is XII, reached by the Chilean 1960 Valdivia earthquake, the strongest ever recorded. The earthquake on 5 February 1783 reached XI on the Mercalli scale, this inferred from the extreme destruction of almost all built structures, and the triggering of landslides and rockslides. This earthquake was an extremely destructive force. These descriptions and the distribution of high earthquake intensities correlate with a Richter magnitude of around 7.0. Frightened by this earthquake, many people spent the night outside; in Scilla many residents slept on the beach. The second large earthquake occurred shortly after midnight on 6 February. A rockslide near Scilla caused a tsunami which killed 1,500 of those people seeking refuge on the beach. Another strong earthquake occurred on 7 February at 1:10 p.m. It was followed by another, on 1 March at 1:40 a.m. The fifth and last large earthquake occurred on 28 March at 6:55 p.m. In June, the King of Naples established the cassa sacra, a governmental body to administer expropriated Church estates to aid reconstruction.

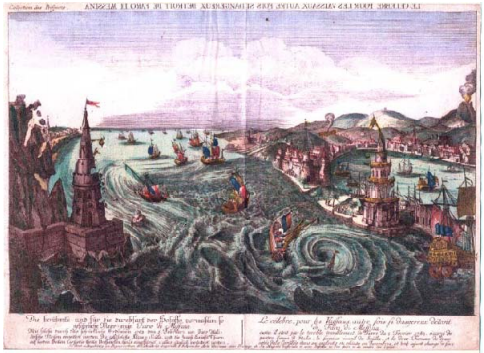

This hand-colored copper engraving portrays the Strait of Messina from the north at the moment the earthquake struck. To the left it depicts the coast of Calabria, to the right the harbor of Messina, and to the far right an erupting Mount Etna (although it did not actually erupt in 1783). Buildings are being damaged, fires spread, and a tsunami (visualized as whirlpools) troubles the ships in the Strait.

This hand-colored copper engraving portrays the Strait of Messina from the north at the moment the earthquake struck. To the left it depicts the coast of Calabria, to the right the harbor of Messina, and to the far right an erupting Mount Etna (although it did not actually erupt in 1783). Buildings are being damaged, fires spread, and a tsunami (visualized as whirlpools) troubles the ships in the Strait.

Unknown artist, n.d.

Courtesy of Jan T. Kozak (Kozák Collection, University of Berkeley).

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Strait of Messina as seen from the Santuario della Madonna di Montalto Church in Messina in 2016. Across the Strait one can see the coast of Calabria; to the right, the harbor of Messina; and, on the horizon to the left, the tower of Faro.

The Strait of Messina as seen from the Santuario della Madonna di Montalto Church in Messina in 2016. Across the Strait one can see the coast of Calabria; to the right, the harbor of Messina; and, on the horizon to the left, the tower of Faro.

Photograph by Katrin Kleemann, June 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This seismic crisis interested many naturalists and scholars such as William Hamilton, British Ambassador in Naples at the time, who wrote about it. Notes about the Calabrian earthquakes can be found in several private weather diaries across Europe. Italy was a celebrated stop on well-heeled Europeans’ grand tour at the time; thus news from the country would have sparked great interest among educated readers.

The earthquakes caused severe damage and destruction in Messina in the foreground and Reggio Calabria in the background, killing and injuring thousands of residents.

The earthquakes caused severe damage and destruction in Messina in the foreground and Reggio Calabria in the background, killing and injuring thousands of residents.

Unknown artist, Vue de la Ville de Regio dil Messinae et ces alentour detruite par le terrible tremblement de Terre arrivée le Cinq Fevrier de l’annee 1783, c. 1790.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 28 May 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

While hundreds of aftershocks still occurred in Calabria and Sicily, another phenomenon was on the horizon. In mid-June 1783, most of Europe and other parts of the northern hemisphere were covered in a sulfuric-smelling dry fog. This “fog” originated from the Icelandic Laki fissure, which erupted from June 1783 to February 1784 and released large amounts of sulfur dioxide and other gases. The world outside of Iceland did not know about this eruption and contemporaries developed several theories as to the origin of this unusual weather. The most popular explanation in the summer of 1783 was the idea that the Italian earthquakes had opened the earth and released sulfuric odor from its depths. The fog was visible some time after the Italian earthquakes actually occurred, but for Europeans outside Italy it coincided with the arrival of the news of the earthquakes.

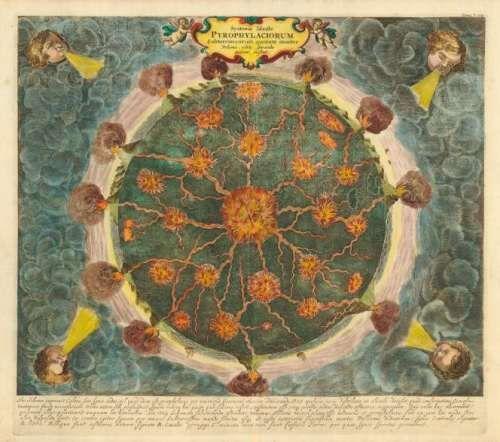

“Subterraneus Pyrophylaciorum”: Fire canals connecting all volcanoes on the planet, depicted in Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus, 1668.

“Subterraneus Pyrophylaciorum”: Fire canals connecting all volcanoes on the planet, depicted in Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus Subterraneus, 1668.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 28 May 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Some contemporaries believed they lived in the time of a “subsurface revolution”: earthquakes in Italy; a newly emerged burning island off the coast of Iceland; reports of at least three volcanic eruptions within Germany (that later proved to be false); earthquakes in western France and Geneva on 6 July, in Maastricht and Aachen on 8 August, and in northern France on 9 December 1783; and reports of Hekla erupting in September.

Where did this idea of a revolution subterraneus come from? There was an idea that all volcanoes, called fire (-spitting) mountains at the time, were connected through fire channels inside the earth. Chemical reactions—between gas or metals and water for instance—in subterraneous passages and caverns were believed to cause earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. In the eighteenth century, Nicholas Lémery, Comte de Buffon, and Immanuel Kant promoted these ideas.

The sheer number of unusual subsurface phenomena seemed overwhelming in 1783. The fear of earthquakes loomed large at the time; the earthquakes of 1783 occurred not long after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the 1756 Düren earthquake. The seismic sequence of Calabria and the Laki fissure eruption occurred during the Late Enlightenment and scientists as well as the educated public were eager to find reasonable explanations for what they witnessed. As the true cause of the unusual weather remained obscure, the subsurface revolution hypothesis addressed many of the unusual phenomena—most prominently the sulfuric smell.

During this period, there was no universal explanation for the earthquakes. The theory of plate tectonics was only accepted in the mid-1960s. Today, we know that the African plate is being subducted under the Eurasian plate. The Tyrrhenian Sea is the backarc basin with volcanism at the Eolian Islands and Etna (the magma is generated by the subducted plate), and normal faulting and uplift all across the Calabrian Arc. The geology of the Calabrian Arc is very complex and remains poorly understood today.

European Seismic Hazard Map: Seismically active areas are colored red, aseismic regions are light green. The locations of Sicily and Iceland become apparent in this map. The insert on the top right shows a map of earthquakes in Europe with a moment magnitude of greater than 3.5 between the years 1000 and 2007. The map was compiled for the SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue (SHEEC).

European Seismic Hazard Map: Seismically active areas are colored red, aseismic regions are light green. The locations of Sicily and Iceland become apparent in this map. The insert on the top right shows a map of earthquakes in Europe with a moment magnitude of greater than 3.5 between the years 1000 and 2007. The map was compiled for the SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue (SHEEC).

Poster/Map: Giardini D., Woessner J. , Danciu L. , Crowley H. , Cotton F. , Grünthal G. , Pinho R., Valensise L. and the SHARE consortium (2013) European Seismic Hazard Map for Peak Ground Acceleation, 10% Exceedance Probabilities in

50 years, doi: 10.2777/30345, ISBN‑13, 978‑92‑79‑25148‑1.

ESHM13 models and results: Woessner, J., Danciu L., D. Giardini and the SHARE consortium (2015), The 2013 European Seismic Hazard Model: key components and results, Bull. Earthq. Eng., doi:10.1007/s10518‑015‑9795‑1.

Data and illustration: Giardini D. et al., (2013), Seismic Hazard Harmonization in Europe (SHARE): Online Data

Resource, doi: 10.12686/SED‑00000001‑SHARE, 2013.

SHARE Project: Giardini, D., Woessner J. , Danciu L., (2014) Mapping Europe’s Seismic Hazard. EOS, 95(29): 261‑262.

Please note the Reference Seismic Hazard Map (Giardini et al , , doi: 10.2777/30345) is a product of the 2013

European Seismic Hazard Model (Woessner et al 2015) developed within the framework of SHARE project (Giardini et al

2014

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

How to cite

Kleemann, Katrin. “Living in the Time of a Subsurface Revolution: The 1783 Calabrian Earthquake Sequence.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2019), no. 30. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8767.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Katrin Kleemann

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Carcione, J. M., and J. T. Kozák. “The Messina-Reggio Earthquake of December 28, 1908.” Studia Geophysica et Geodaetica 52 (2008):661–672.

- Graziani, L., A. Maramai, and S. Tinti. “A Revision of the 1783–1784 Calabrian (Southern Italy) Tsunamis.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Science, Copernicus Publication on behalf of the European Geosciences Union 6, no. 6 (2006):1053–1060.

- Hamilton, William. An Account of the Earthquakes in Calabria, Sicily, &c. As Communicated to the Royal Society. Colchester: J. Fenno, 1783.

- Jacques, E., C. Monaco, P. Tapponnier, et al. “Faulting and Earthquake Triggering During the 1783 Calabria Seismic Sequence.” Geophysical Journal International 147 (2001): 499–516.

- Parrinello, Giacomo. Fault Lines: Earthquakes and Urbanism in Modern Italy. New York: Berghahn Books, 2015.

- Placanica, Augusto: Il filosofo e la catastrophe: Un terremoto del Settecento. Turin: Einaudi, 1985.

- Unknown author. Historische und geographische Beschreibung von Messina und Calabrien, und meteorologische Beobachtungen über das Erdbeben, welches diese Stadt und Landschaft den 5. Hornung 1783 verwüstet hat. Straßburg: Albrecht Friedrich Bartholomäi, 1783; particularly, p. 18ff.