View over the Bavarian National Park

View over the Bavarian National Park

Photograph by Herbert Pöhnl

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Bavarian Forest National Park, situated in South-Eastern Germany along the border with the Czech Republic, was established as the country’s first national park in October 1970. Extended in 1997 to its present size of 243km², the park comprises a densely forested low mountain range of an average height of 600–1456m. Together with the adjacent Bohemian Forest National Park (cz. Národní park Šumava, under national park status since 1991) in the Czech Republic, it preserves the largest area of continuous forest in Central Europe.

Remnant pockets of original forest meant that the area was considered particularly suitable for a nature reserve ever since the increase in conservationist sensibilities of the late nineteenth century. The imperial annexation of Czechoslovakia by the Nazi Regime in 1938 spawned concrete plans for the demarcation of an expansive “Bohemian Forest National Park” which were ultimately thwarted by the Second World War. However, propositions for a national park on the German side of the border resurfaced when the Iron Curtain isolated the eastern and the western half of the Bohemian Forest ecosystem.

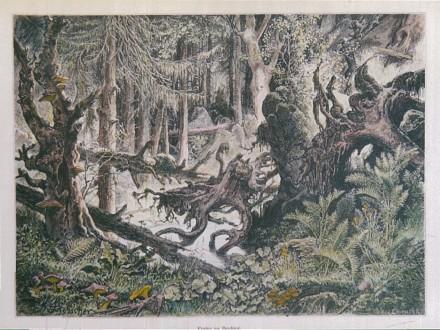

Historical illustration of the “primeval” Bavarian Forest

Historical illustration of the “primeval” Bavarian Forest

Historical illustration by Karel Liebscher [1874?]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In the middle of the 1960s, local and regional governmental initiatives to attract tourism to an underdeveloped rural backwater combined with German conservationists’ long quest for a substantial reserve. This time, the moral weight and media leverage of celebrity conservationist Bernhard Grzimek provided the campaign with vital momentum and public appeal. Convinced that a national park in the area was the last chance to give an increasingly urbanite society an encounter with the “original” nature of the German past, Grzimek originally envisioned the introduction of elk, bear, bison, and wolves into what was until then largely a sustainably managed forest. This proposal, derived from his experience with national parks in East Africa, sparked year-long controversies with the forestry service and parts of Germany’s conservation establishment. Ultimately, the proposed “original” fauna was relegated to gated compounds.

The predominant focus on tourism and regional development resulted in an initial lack of conservationist purpose in the park. A heavy windstorm in 1983 was to become the decisive watershed for the evolution of a consistent management philosophy. The park administration left some 90 hectares of the fallen timber to rot and opted to no longer interfere with natural processes in the core zone of the park. “Let nature be nature” became the new guiding principle, an approach that was severely challenged when the rotting wood became infested by bark beetle (Ips typographus) in the wake of further windfalls during the 1990s.

The beetle not only threatened cultivated forests outside the park border but also resulted in vast areas of dead trees with little aesthetic appeal for tourists and locals alike. In addition to preventive measures against the insect’s further spread, the Park Service responded to the outcry by improved public communication, conveying a different image of the beetle not as a pest but a vital keystone species for the natural cycles of coniferous forests.

New forest growing between the national park’s deadwood

New forest growing between the national park’s deadwood

2013 Herbert Pöhnl

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This practice of protecting processes has made the park a laboratory for new ecologically anchored meanings of wilderness in Central Europe, a site for educating people to embrace a dynamic understanding of their homeland nature, and the key reference for current controversies over the establishment of further forest national parks in Germany.

The last 20 years have also seen the park emerge into a laboratory of nature uniting nations. Exploiting the opportunities provided by pledges in a number of international treaties—such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Habitats Directive, and the Natura 2000 network—Czech and German park authorities have increased cooperation in park management and set up management guidelines for a joint wilderness area branded as the “wild heart of Europe.” These efforts at transboundary conservation vividly illustrate the degree to which the borders, peripheries, and dead zones of the Cold War have been transformed into exciting hotbeds for adapting conservation to the political and social needs of the 21st century.

How to cite

Gissibl, Bernhard. “A Laboratory for the Implementation of “Wilderness” in Central Europe—The Bavarian Forest National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2014), no. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5856.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2014 Bernhard Gissibl

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Chaney, Sandra. Nature of the Miracle Years: Conservation in West Germany, 1945–1975. New York; Oxford: Berghahn, 2008.

- Engels, Jens Ivo. Naturpolitik in der Bundesrepublik. Ideenwelt und politische verhaltensstile in Naturschutz und Umweltbewegung 1950–1980. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2006.

- Gissibl, Bernhard. "A Bavarian Serengeti: Space, Race and Time in the Entangled History of Nature Conservation in East Africa and Germany." In Civilizing Nature: National Parks in Global Historical Perspective, edited by Bernhard Gissibl, Sabine Höhler, Patrick Kupper, 102–19. Oxford, New York: Berghahn, 2012.

- Kangler, Gisela. "From the Bohemian Forests to the Bavarian Forest National Park—the Change of Meaning of a Wilderness in Europe," In Cultural Heritage and Landscapes in Europe [Landschaften: Kulturelles Erbe in Europa], edited by Christoph Bartels and Claudia Küpper-Eichas, 313–30. Bochum: Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, 2008.

- Křenová, Zdeňka Hans Kiener. "Europe’s Wild Heart—Still Beating? Experiences from a New Transboundary Wilderness Area in the Middle of the Old Continent." In European Journal of Environmental Sciences 2, 2 (2012): 115–24.

- Pöhnl, Herbert. Der halbwilde Wald. Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald: Geschichte und Geschichten. München: oekom 2012.