In 1967, Lynn White famously located the roots of the ecological crisis in Western Christianity. Interestingly, White argued that since the roots are religious, the remedy must also be religious. He suggested an alternate Christian worldview based on an idea inspired by the thirteenth-century Catholic mystic, Francis of Assisi—that all creatures are equal. Almost fifty years later, the first pope from the global South chose the name Francis, inspired by the same mystic. Pope Francis has been acclaimed as the most powerful ally of the environmental justice movement, thanks to his 2015 encyclical Laudato si’.

Jan Siberechts, Heilige Franciscus van Assisi predikt voor de dieren [Saint Francis preaching to the animals], 1666. Oil on canvas, 235.7 x 312.7 cm.

Jan Siberechts, Heilige Franciscus van Assisi predikt voor de dieren [Saint Francis preaching to the animals], 1666. Oil on canvas, 235.7 x 312.7 cm.

Painting by Jan Siberechts, 1666.

Held by Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 23 May 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The strand of “religious environmentalism” advocated by Pope Francis is not surprising: he belongs to a Catholic order (the Jesuits) whose founder was a nature lover himself—Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556). In his Spiritual Exercises, considered the foundational document for Jesuit spiritual training, Ignatius asks the Jesuit trainee to consider how God dwells in creatures, elements, plants, animals, and human beings. This tradition of contemplating how God dwells in all earthly beings has informed the global Jesuit mission, including in India.

In 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm highlighted the growing conflict between environmental conservation and economic development in the “developing” world. In 1975, the Jesuits renewed their global mission to be “the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement. For reconciliation with God demands the reconciliation of people with one another” (Society of Jesus 1975). This renewed mission, along with the Jesuits’ eco-centric spirituality took the shape of ‘socio-environmental justice’ in the Jesuits’ missionary practice in South India.

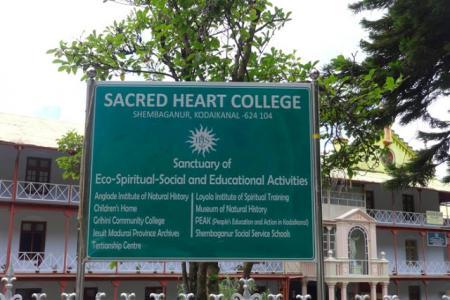

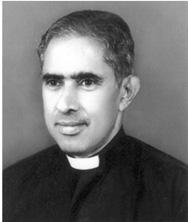

The Palni Hills are located in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu. In 1895, the French Jesuits established the Sacred Heart College at Shembaganur, situated amidst the Palni Hills, to train Jesuit novices. Influenced by the scientifically minded European Jesuits, the novices were also trained in the natural sciences. One young novice, K. M. Matthew (1930–2004), acquired his doctorate in plant taxonomy of the Palni hills, even before he was ordained a priest in 1965. In 1967, Father Matthew established the Rapinat Herbarium, a center specializing in systematic botany and conservation research. Over the next few decades, Matthew pioneered environmental research and conservation efforts across the Palni Hills.

Fr. K. M. Matthew (1930–2004).

Fr. K. M. Matthew (1930–2004).

Courtesy of the Rapinat Herbarium. Click here to view source.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) released the first Report on the State of India’s Environment in 1982, which argued that environmental conservation must go hand in hand with economic development. CSE’s report followed the 1980 publication of World Conservation Strategy (WCS), the first major international report to prioritize conservation as a public policy issue. Meanwhile, the Palni Hills gained popularity as a tourist destination in the 1980s, with disastrous effects on its ecology. Concerned citizens, keen to restore the pristine habitats of the Hills, founded the Palni Hills Conservation Council (PHCC) in 1985, with Matthew as its Founder-Vice President. He also established the Anglade Institute of Natural History in 1984 to expand the conservation efforts in the hills. Supported by the Government of India, Matthew launched a residential training program in environmental conservation and sustainable development. The program drew from the CSE and WCS reports, but he adapted it to the needs of the local people and regional ecology. Even after Matthew’s demise in 2004, the program continues to be in vogue and has since been adapted to different audiences—students, teachers, government officials, village leaders, and women—and trained almost a million people till date.

Scholars have often hesitated to link the literature on religion and ecology to the literature on environmental conservation because religion is often identified with enviro-skepticism. It is true that many climate change deniers are influenced by Christian worldviews. But to insist on a radical, secular worldview is refusing to engage with vast religiously inclined populations. Encouragingly, institutions like the Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale seek to understand both the problems and the promises of religion in responding to environmental crises. As Handley (2016) suggests, acknowledging religious motivations can help shape environmentalism within the religious worldviews that operate in a majority of the global population. For example, Kent (2013) has explored how the sacred groves of Tamil Nadu do not just embed the beliefs of the local people but also articulate the pragmatic needs for socio-environmental justice. Likewise, the social history of the kulam (water tanks in Hindu temples) in Tamil Nadu indicate the environmental role fulfilled by a place of worship—protection of groundwater resources.

Fr. Matthew’s redefinition of the Jesuit mission as one that reconciles humanity with creation is noteworthy for the advocacy of environmental justice. His pioneering efforts in preserving the ecological diversity of the Palni Hills offers an example of religious environmentalism. Significantly, the Jesuits also note that human rights include “rights such as development, peace and a healthy environment” and recommend alternative development models which “integrate cultural, environmental, and social justice values in their functioning” (Czerny 1999). The cause of environmental justice stands to gain from eco-theological ideas espoused by religious communities like the Jesuits. As White argued, these religious ideas can help in identifying a multi-pronged remedy for our current ecological crisis.

How to cite

Vedanayagam, Joseph Satish. “Engaging Religion in the Fight for Environmental Justice: Jesuits and Conservation in the Palni Hills of South India.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2019), no. 24. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8768.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Joseph Satish

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Czerny, Michael, ed. “‘We Live in a Broken World’—Reflections on Ecology.” Social Apostolate Secretariat at the General Curia of the Society of Jesus. Promotio Iustitiae 70 (1999).

- Handley, George B. “Laudato Si’ and the Postsecularism of the Environmental Humanities.” Environmental Humanities 8, no. 2 (2016): 277–84.

- Ignacimuthu, Savarimuthu. “The Contributions of South Asian Jesuits to Environmental Work.” Journal of Jesuit Studies 3, no. 4 (2016): 619–44.

- Kent, Eliza F. Sacred Groves and Local Gods: Religion and Environmentalism in South India. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Matthew, K. M. “Environmental Awareness and Ecodevelopment in India: A Training Programme for Students.” Environmental Conservation 13, no. 4 (1986): 351.

- Society of Jesus. “Our Mission Today: Service of Faith and the Promotion of Justice.” General Congregation 32, decree 4, 1975.

- White, Lynn. “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.” Science 155, no. 3767 (1967): 1203–7.