Castlemaine (Central Victoria, Australia) is a small rural town, initially established in the mid-nineteenth century by white settlers attracted to one of the world’s most lucrative gold diggings. Today, my hometown is known for its artistic and sustainability-orientated initiatives—a living exemplar of the point made by DeVlieg (2011, 15) that “[a]rt that debates the challenges of climate change and sustainability is able to bring distant concepts to a local level and is therefore able to be more effective at empowering communities.”

From the late 1960s, our area has attracted successive waves of creative urban dwellers resettling agricultural and bush land with the intertwined aims of artistic practice and self-sufficiency and, more recently, communal sufficiency. Local writer Katherine Seppings (RBA 2016, 148) explains that initially “some squatted in bush land and constructed houses made from earth and stone; others recycled windows and doors from the miner’s ruins, resurrecting handmade bricks and old timbers carved and painted, from the tips, from abandoned hotels, houses, and stores, creating energy efficient building techniques and inventing environmentally sustainable ways of life.”

Since then simple and convivial degrowth (D’Alisa et al. 2014) styles of sustainability have proliferated, offering the arts as powerful forms of communication. For instance, in 2007, senior students of Castlemaine North Primary School in Victoria projected possible futures under climate change in a mural that would stand vibrant and poignant for a decade on a central street wall. This local–global mural was based on local knowledge, childrens’ points of view, and scientific forecasts of the IPCC (2006).

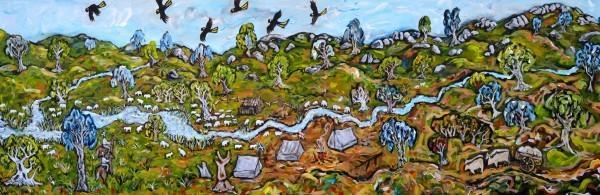

Castlemaine mural (2007–2017) by local children from Castlemaine North Primary School showing their view of climate change.

Castlemaine mural (2007–2017) by local children from Castlemaine North Primary School showing their view of climate change.

Photo by Shirley Lewis (“The Baglady”), Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia, 2015.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The thermometer—set like a vertical spear in the middle of the mural—signified our central challenge today. Current global temperatures resulting from past activities were painted on the left and, conversely, impacts on the future on the right. Negative impacts of global warming were painted at the top and a more hopeful, less damaged, future with diminishing carbon emissions at the bottom. Local artists, such as Ben Laycock, supported and guided classes that imagined, composed, and executed the mural.

At least 10 percent of Castlemaine residents are practicing artists, many of national, even international, repute. The two-week biennial Castlemaine State Festival of the arts is renowned. Thanks to activists such as Laycock, it’s offspring Castlemaine Fringe Festival operates year-round. Another homemade Lot 19 space with studios, galleries and printing press workshop is much more than an artists’ hub. Similarly, a plethora of sustainability activities occupy the decade-old Mount Alexander Sustainability Group with its local target for net zero emissions by 2025.

Diurnal and nocturnal life at the arts hub Lot 19.

Diurnal and nocturnal life at the arts hub Lot 19.

Photos by Mark Anstey, they can be found on the Lot 19 website.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Local activists work towards environmentally sustainable futures distinct from, yet embodying, traditional Aboriginal wisdom that holds that humanity lives with, off, by—even for—nature. Respect for “country” (Earth) is redolent in art produced locally, say by Eliza Tree, a white “Castlemaniac” (as we fondly call ourselves) and by sustainability activists regenerating the land with a biodiversity focus, in activities promoted by groups such as Connecting Country (MA region).

Eliza Tree: “Jaara Country to Gold Rush #2.”

Eliza Tree: “Jaara Country to Gold Rush #2.”

This artwork was produced and photographed by Eliza Tree.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Despite decimation of their numbers as a result of the white invasion (1830s), Aboriginal peoples—particularly the Liarga Balug clan of the Dja Dja Wurrung—have occupied this area for an estimated 50,000 years. Before the erosion of traditional lifestyles, patrilineal clans divided into cross-marrying Bunjil (Eaglehawk) and Waa (Crow) moieties. Culture and “country” held hands just as now we strive to stand on the two feet of creativity and sustainability. Those aspiring to low-impact living today revere the simple living of traditional Indigenous peoples who, here, subjected Box-Ironbark woodlands to environmentally sensitive “fire-stick farming” and satisfied most of their basic needs with some additional tools and materials sourced in exchange networks that in centuries past crisscrossed the continent.

Later, with the massive migrations of the mid-nineteenth century, the rich ecology of local woodlands was destroyed as broad-scale clearing for building, mining, manufacturing, agriculture, and transportation took place. Waterways were redirected and storage dams and large reservoirs created. Such transformations not only left simple coppice regrowth but also architectural and machinery remains—some protected for posterity and tourists within the impressive Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park (2002–). This denuded landscape and its residents have been subject to serious droughts, extensive flooding, bushfires, and violent storms—all such extremes becoming more intense and frequent with climate change, and demanding sensitive and complex social and environmental responses.

The work of regeneration through low impact living practices has drawn on “permaculture,” which is based on traditional and modern approaches to sustainable settlement, gardening, and farming as a resilient response to climate change. Permaculture’s co-founder David Holmgren lives in an adjacent municipality. Local collective sufficiency expresses itself in the food-oriented activities of Growing Abundance (GA) whose principles are “respect,” “replenish,” and “rejoice,” a weekly market replete with fresh organic produce, second-hand and homemade goods and services, as well as art and craft work, and monthly local farmers’ and artists’ markets. The volunteer GA Harvest Project saves surplus fruit, dividing it equally between harvesters, tree owners, and relevant local community organizations, including preserving it for school canteens—in other words, developing sustainable economies as well as regenerating landscape ecologies.

As illustrated in their mural, our children not only face the future with an awareness of the threats of global warming and destruction wrought by mining activities, but are armed with local knowledge and everyday skills to apply in confident and resilient ways so that they embrace the future with their arms and eyes wide open.

How to cite

Nelson, Anitra. “Castlemaine: Climate Change, Consciousness, and Art.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2017), no. 30. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8116 (link is external).

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2017 Anitra Nelson

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- D’Alisa, G., F. Demaria, and G. Kallis. Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Paradigm. London: Earthscan, 2014.

- DeVlieg, Mary Ann. “Arts, Culture and Sustainability: Visions for the Future.” In Arts. Environment. Sustainability. How Can Culture Make a Difference?, edited by Claire Wilson. Singapore: Asia-Europe Foundation, 2011.

- IPCC.Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Geneva: International Panel on Climate Change, 2006.

- RBA. Mount Alexander Shire Thematic Heritage Study: Thematic History Vol. 2. St Kilda: RBA Architects + Conservation Consultants, 2016.