In 1966, the French historian Albert Silbert published his doctoral thesis Le Portugal Meditérranéen à la fin de l’Ancien Régime, defended two years earlier at Sorbonne University. The result of two decades of research, his thesis carefully reconstructed the rural economy of the southern regions of Beira Baixa and Alentejo at the turn of the eighteenth to the nineteenth century. A disciple of the Annales school, Silbert described a complex socio-ecological mosaic of cultivated fields, moors (charnecas), common lands (baldios), woodlands (matas) and pastures. Le Portugal Meditérranéen became a landmark in the rural and economic history of Portugal, influencing generations of scholars. One aspect of this work, however, has been curiously overlooked: the role of fire as a crucial element of the rural landscape.

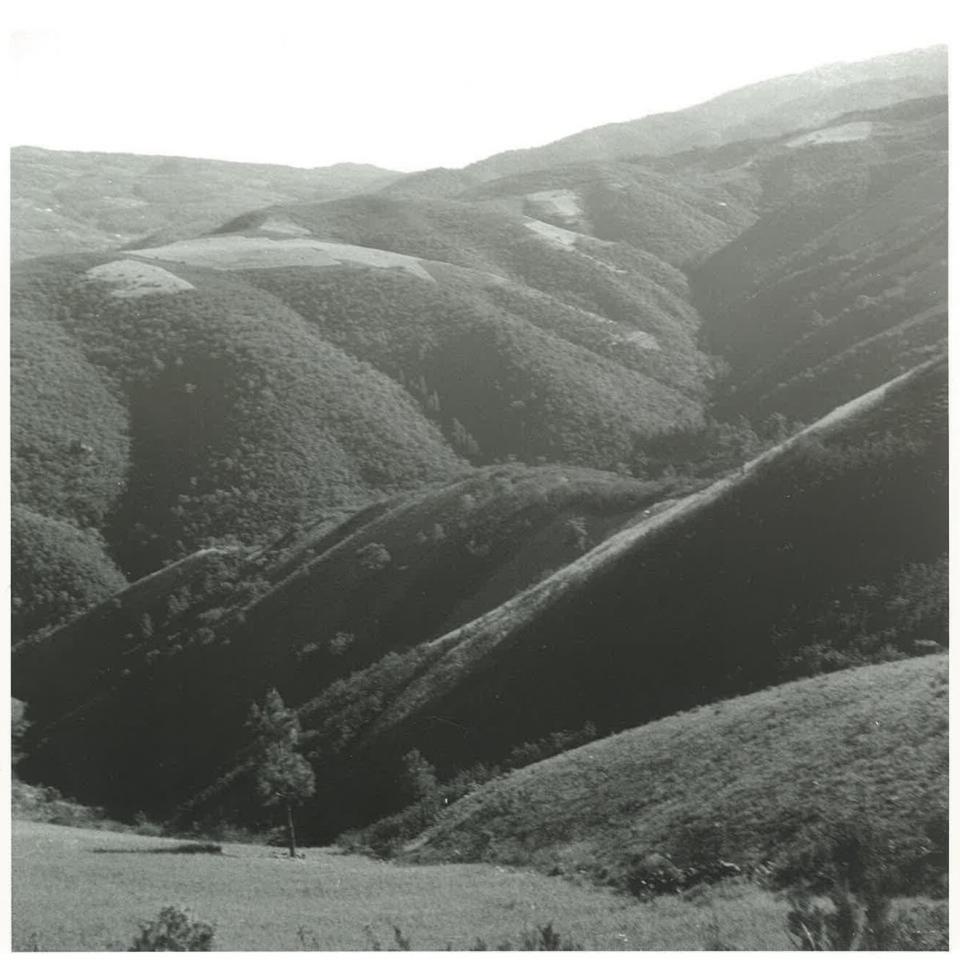

Serra de Monchique from the Sabóia road. Photo taken in April 1965 by António Maria Callapez. The white patches on the hills are rainfed fields, probably wheat, surrounded by scrub and scattered trees.

Serra de Monchique from the Sabóia road. Photo taken in April 1965 by António Maria Callapez. The white patches on the hills are rainfed fields, probably wheat, surrounded by scrub and scattered trees.

© 1965 António Maria Callapez. Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

At a time when major wildfires pose increasing ecological, economic, and social threats, looking back at this historical role of fire and its progressive exclusion from the rural landscape gives new context to contemporary challenges.

Sickle with a reinforced toe used for clearing. Kept by a former farmer in a small mountain village in Monchique, who described to the Burning Landscapes project the roça e queima practices still in use in the 1960s.

Sickle with a reinforced toe used for clearing. Kept by a former farmer in a small mountain village in Monchique, who described to the Burning Landscapes project the roça e queima practices still in use in the 1960s.

Photo by the Burning Landscapes Project Team.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The pervasiveness of fire in the rural economy studied by Silbert is hard to overstate. For eighteenth-century Portuguese peasants, fire was part of everyday life. It was used to make charcoal, renew pastures, and burn the vegetation to clear and fertilize the soil for the cultivation of cereals (rye, wheat, barley) in the vast charnecas and common lands. This type of swidden cultivation (roças and queimadas) was particularly important in mountain areas, but it was also present in the plains of Alentejo, where municipal authorities collected revenue from these burning landscapes. Generally, the vegetation was cut in the spring and left to dry until August, when it was set alight. With the onset of the first rains, cereals were planted. Reflecting on this cycle, Silbert observed that “from the north to the south of Alentejo, as from the east to the west, cultivation by burning, by roças, and queimadas, was a system … it was not sporadic or supplementary, but a mode of production that occupied a central place in agricultural life.” He went on to note similarities with the forms of swidden cultivation common in the tropics, going so far as to question whether the roças and queimadas had prepared the Portuguese for the landscapes they would encounter in their colonial empire.

When Silbert first visited Portugal in the late 1940s, traces of this fire-centric rural economy were still widespread. But traditional burning landscapes were changing rapidly and fire was increasingly perceived as a threat. Restrictions had existed since the Middle Ages, particularly around royal forests and hunting grounds. From the 1700s onwards, however, enlightened agrarian reformers began to denounce roças and queimadas as destructive practices that contributed to the backwardness of Portuguese agriculture (Portugal 1791). After the consolidation of the modern liberal state in the 1830s, the confiscation and sale of ecclesial and other entailed properties and the privatization of common lands slowly undermined the socio-ecological mosaic that prevailed at the end of the eighteenth century. Meanwhile, the development of scientific forestry led to an increasing regime of control. In 1886, the newly created Serviços Florestais (Forestry Service) banned queimadas within 200 meters of state forests; this was extended to one kilometer in 1926.

These trends accelerated with the establishment of the Estado Novo (New State) dictatorship in the late 1920s. The flagship policies of the new regime included the transformation of the remaining “uncultivated” charnecas into a wheat monoculture and the conversion of the upland commons of the northern half of the country into state forests, as preconized by the Wheat Campaign of 1929 and the Afforestation Law of 1938. These “fascist modernist landscapes,” as Tiago Saraiva recently described them, were imagined as landscapes without fire. The movement to exclude fire was backed by a growing scientific consensus among foresters and agronomists, who inscribed it within a long-standing narrative of anthropogenic environmental destruction of the Mediterranean basin and a critical discourse that condemned swidden cultivation as a practice of “primitive people” (Guerreiro 1958).

Serra de Monchique in June 2022. Photo taken at Perna da Negra where the mega fire of 2018 started. Four years after the fire, vast new eucalyptus plantations can be seen.

Serra de Monchique in June 2022. Photo taken at Perna da Negra where the mega fire of 2018 started. Four years after the fire, vast new eucalyptus plantations can be seen.

Photo by the Burning Landscapes Project Team.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

By the mid 1960s, when Silbert published his thesis, state-sponsored efforts to turn Portugal into a “forest country” had extended southwards and into privately owned land, through the incentives provided by the Fundo de Fomento Florestal (Forest Development Fund). A standardized forest of fast-growing species like the Eucalyptus globulus became increasingly common, providing raw materials for the paper pulp industry. As a result, the publication of the most comprehensive historical analysis of the role of fire in the Portuguese rural economy coincided with its demise. Indeed, at the end of the decade, the regional commander of the Portuguese gendarmerie in the south of the country called for a ban on queimadas until the end of September, arguing that they caused numerous wildfires that “greatly affect the national economy and state assets.”

Today, the burning landscapes that were once prevalent across the country have been consigned to the past. Nonetheless, the attempts to exclude fire that accompanied state afforestation policies have largely backfired. Wildfires have become increasingly common and destructive, ravaging a territory made more combustible by a hazardous combination of rural flight, scrub encroachment, eucalyptus and pine monocultures, and climate change. In the summer months, once devoted to roças and queimadas, warnings about the ever-present risk of wildfires dominate the airwaves. In an ironic twist of fate, the traditional uses of fire depicted by Silbert are now presented by experts as a way out of this fiery conundrum.

How to cite

Ferreira, José, Miguel Carmo, Inês Gomes, Marta N. Silva. “Roças and queimadas: Changing Landscapes of Fire in Twentieth-Century Portugal.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2025), no. 9. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/9983.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2025 José Ferreira, Miguel Carmo, Inês Gomes, and Marta N. Silva.

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- “Captain José da Costa Pires to the Civil Governor of Faro.” Arquivo Distrital de Faro, Governo Civil do Distrito de Faro, E, B, 12, 3218, 6 September 1967.

- Guerreiro, Manuel Gomes. Problemas Florestais na Região Mediterrânea ao Sul de Portugal. Lisbon: Junta Nacional da Cortiça, 1958.

- Oliveira, Emanuel de, M. Conceição Colaço, Paulo M. Fernandes, and Ana Catarina Sequeira. “Remains of Traditional Fire Use in Portugal: A Historical Analysis.” Trees, Forests and People 14 (2023). doi:10.1016/j.tfp.2023.100458.

- Oliveira, Tiago M., Nuno Guiomar, F. Oliveira Baptista, José M. C. Pereira, and João Claro. “Is Portugal’s Forest Transition Going Up in Smoke?” Land use Policy 66 (2017): 214–26. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.04.046.

- Portugal, Alexandre António das Neves. “Apontamentos sobre as queimadas em quanto prejudiciaes à agricultura.” In Memórias Económicas da Academia Real das Ciências de Lisboa, vol. III, edited by José Luís Cardoso, 245–49. Lisbon: Banco de Portugal, 1991 [1791].

- Saraiva, Tiago. “Fascist Modernist Landscapes: Wheat, Dams, Forests, and the Making of the Portuguese New State.” Environmental History 21, no. 1 (2016): 54–75. doi:10.1093/envhis/emv116.

- Silbert, Albert. Le Portugal Méditerranéen à la Fin de l'Ancien Régime, XVIIIe – Début du XIX. Siècle: Contribution à l'Histoire Agraire Comparée. Paris: S.E.V.P.E.N., 1966.