Ruptures

Wetland landscapes hold within them layered timescapes: tidal pulses, seasonal migrations, rhythms of rain and drought, agricultural cycles, ancient settlements, and the creeping inevitability of industrial modernity. Yet rupture—the moment of profound breakage or collapse, where temporalities visible and dramatically clash—materializes most starkly where the human will to dominate meets the volatility of wetland ecologies.

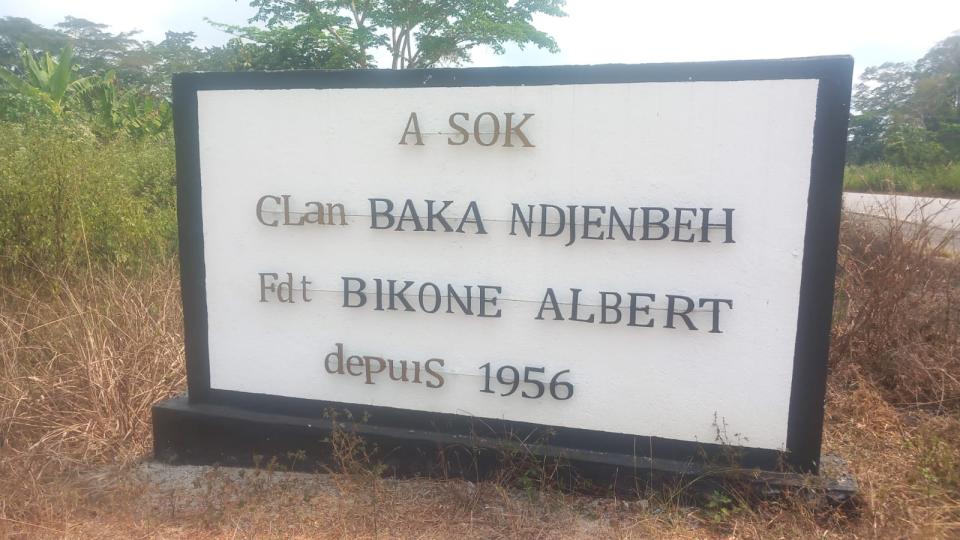

Figure 23: Clan Baka Ndjenbeh welcome sign, A-sok, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

Figure 23: Clan Baka Ndjenbeh welcome sign, A-sok, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

© 2025 Blake Ewing. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The first wave of expulsion of the Baka from their forest homes began the 1950s, shortly after the creation of the Dja Faunal Reserve. But not all resettlement was forced. Some groups were drawn to the roads and their sounds. There they met Bantu people who taught them how to plant. In return, the Baka helped them hunt and showed them how and when to collect honey. One of the villages we visited was founded with the help of an Italian missionary. Now the only remaining villages in the Reserve lie on the very outskirts, just over the Dja river on the north side. During our trip to the Mintom II area, on the south side, we never crossed the river into the reserve. There were no Baka to speak with on the other side.

Displacement is not just spatial; it is temporal. Rupture is a past and future broken apart from each other. But the roadside Baka villages feel very much in between a past and future. A roadside present in between a past living in the forest, and a commercialized and urbanizing world from which they remain estranged. In some sense, then, the rupture does not look like a clean break. After moving, or being moved, from what is now the Dja Reserve, the Baka’s access to a healthy forest that surrounded them has been diminishing over time. Roads, logging, mining, and overhunting are isolating the Baka further, raising calls for allowing them to spend more time in the Reserve to practice their traditional way of life, including hunting animals for subsistence and religious purposes. But for many residents there is no going back.

On the Wadden Sea coastline, rupture can take the form of loss by extreme flooding, made worse by rising seas which are a consequence of anthropogenic climate change. The region bears scars of catastrophic floods like the 1219 storm surge (“First St. Marcellus flood”), which claimed 36,000 lives, and the 1362 “Second St. Marcellus Flood” or Grote Mandrenke (Low Saxon for “Great Drowning of Men”), which drowned 25,000 and wiped out entire communities, including the legendary town of Rungholt. These events, though historical, remain ingrained in collective memory and shape the local understanding of the environment as both cyclical and episodic. In recent decades, storm surges with sea-level rises of more than two meters have tripled, increasing the vulnerability of the region. Floods in 1981, 1990, and 1999 highlight the growing frequency of these events, while islands like Langli, though still existing, are increasingly vulnerable to the forces of erosion and shifting tides. Lands like Jordsand, once part of the mainland, have disappeared. Despite flood protection efforts, such as the 1981 dyke in Fanø, the increasing frequency of floods underscores the fragility of the land.

Figure 24: Stormflodshøjder (storm surge height marker) in Fanø, Denmark, showing the worst flood to date on 24 November 1981. Photograph by Enaiê Mairê Azambuja, March 2025.

Figure 24: Stormflodshøjder (storm surge height marker) in Fanø, Denmark, showing the worst flood to date on 24 November 1981. Photograph by Enaiê Mairê Azambuja, March 2025.

© 2025 Enaiê Mairê Azambuja. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In Morecambe Bay, the looming presence of Heysham nuclear power station marks a particularly charged rupture—both spatial and temporal. Constructed in the 1970s and licensed to operate until 2030, Heysham 1 and 2 rise as concrete sentinels above a mutable shore, asserting a vision of time that is linear, extractive, and stretches long into the future. Their monolithic forms exist in uneasy dialogue with the estuary’s tidal breathing—its cycles of erosion, deposition, migration, and retreat. Beyond the ecological tension lies an economic one: The decline of small-scale fishing in the bay, once a cornerstone of local identity, has forced many residents to seek employment at the power stations. As artist and researcher Debbie Yare remarks, “Everyone knows someone who works there.” This economic entanglement complicates any critique of the nuclear presence.

The stations offer stability where fishing has faltered, anchoring families amid broader precarity—but at a cost. The facilities impose a constant, invisible anxiety: Emergency evacuation zones blur the boundaries of home, while the question of decommissioning haunts the horizon of renewal. The challenge is not solely technical—how to dismantle without contaminating a fragile habitat—but symbolic. Nuclear infrastructure embeds the land into timelines of risk that stretch far beyond human memory, binding it to futures shaped by the inertia of past decisions. The vision for a postnuclear bay—one that centers on wind energy, community stewardship, and ecological repair—remains nascent, aspirational, and deeply tethered to the legacies of rupture.

Figure 25: “Mirror Man,” part of the “Settlement” installation by Rob Mulholland, Half Moon Bay, 2018. Photograph by Gordon Walker.

Figure 25: “Mirror Man,” part of the “Settlement” installation by Rob Mulholland, Half Moon Bay, 2018. Photograph by Gordon Walker.

© 2018 Gordon Walker. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Wetlands are not simply sites of ecological richness, but of temporal negotiation. In the responses to each of these ruptures lie flickers of possibility—glimpses of futures shaped not by extraction, but by adaptation and repair. In several villages close to the Dja Faunal Reserve, we hosted an exercise called the “futures triangle,” a method that helps communities explore how hopes for the future, the weight of past traditions, and present challenges interact to shape their path forward. Amid at times heated discussion, villages deliberated how to best navigate the “pull” of the future in relation to the “weight” of the past. With the help of NGOs like the Congo Basin Institute’s School of Indigenous and Local Knowledge (SILK) (an institutional partner to the Wetland Times project), villagers are making sure younger generations know the old ways.

But the strongest feeling was for adapting, especially making sure the young are educated and have opportunities. During the exercise, the Baka posed many rhetorical questions. Who would refuse a car ride to get to Djoum (a nearby town)? Who can stop a young person from having a mobile phone? The TV informs, even if it is bad for the eyes. What they can control, it was felt, is to try and “slow down” (ralentir) some harmful modern practices. As one participant put it, “on ne doit pas embrasser le modernisme aveuglément” (“We must not embrace modernity blindly”).

Keywords: displacement, loss, future, adaptation

Link words: cycles, histories, tradition, impermanence, memory

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter