(A)synchronicities

Wetlands hold time unevenly. Here, tidal cycles, ecological rhythms, and human schedules intersect—but rarely align. Moments slip past one another: Seasonal patterns clash with policy timelines, and ancestral knowledge contends with the disruptions of climate change and development. These are landscapes of layered time, where histories persist beneath the surface even as futures are abruptly redrawn. The rhythms of water, soil, and species move at a different pace than human attempts to regulate or control them, producing a constant tension between what is remembered, what is unfolding, and what cannot be anticipated. In these spaces, time is not singular but fractured—held in suspension, pulled in multiple directions, and increasingly marked by temporalities out of sync.

In Morecambe Bay, the tension between natural forces and human interventions is acutely felt. The landscape, constantly reshaped by erosion, accumulation, and shifting tides, has become a place of uncertainty for fishermen like Steve Brown of Fleetwood. These forces are not abstract to him—they are daily realities that literally alter the ground beneath his feet. “The sands move all the time—sometimes you don’t know what’s going to be there from one day to the next,” he says. Once-reliable coastlines have become unpredictable, a shift intensified by engineered changes such as modified tidal channels and river straightening. These interventions have disrupted traditional fishing grounds, making areas that were once rich in mussels, cockles, or shrimp vanish or reappear with little warning. The Queen’s Channel and the North Run, altered to manage tidal flow, have unintentionally redirected sediment and reshaped vital shrimping zones. As a result, Steve’s fishing methods, especially in the River Wyre, have evolved; what was once a practice grounded in memory now demands constant adaptation and relearning, reflecting a deep awareness of the landscape’s ongoing transformation.

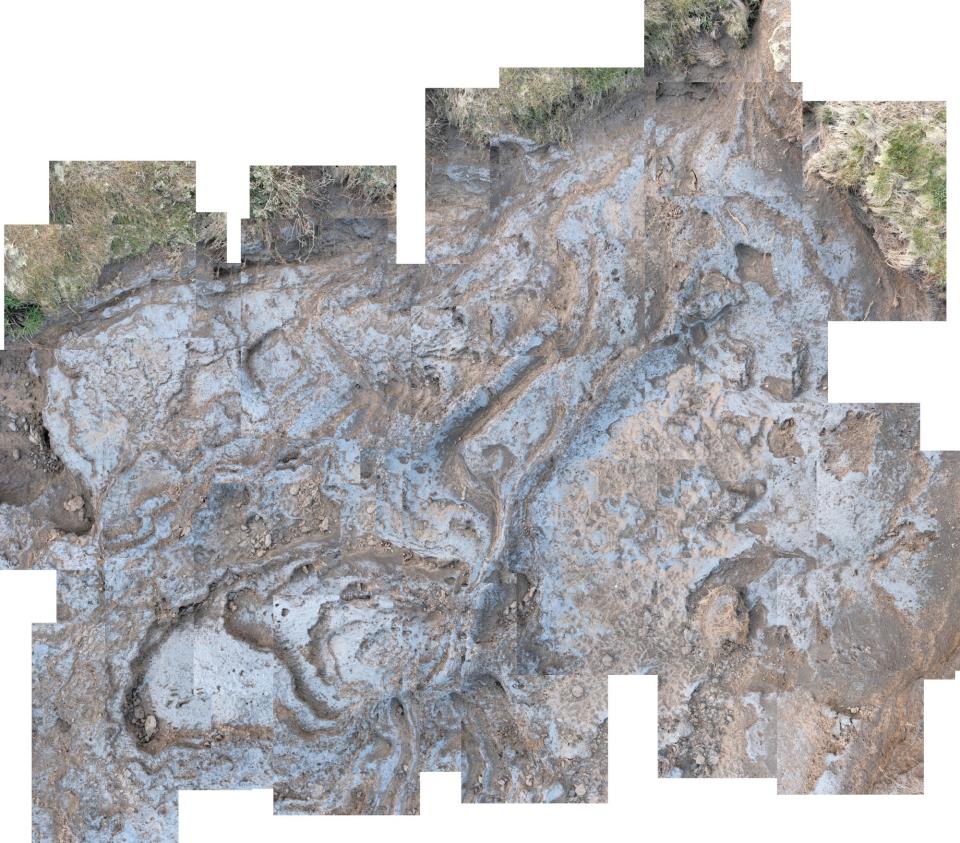

Figure 20: “Imperfect Earth Study” (the movement of the body/camera across the ground at the edge of an eroding salt marsh). Collage by Debbie Yare, April 2022.

Figure 20: “Imperfect Earth Study” (the movement of the body/camera across the ground at the edge of an eroding salt marsh). Collage by Debbie Yare, April 2022.

© 2022 Debbie Yare. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Margaret and Trevor Owen, longtime fisherfolk from Overton, have seen how human interventions have increasingly disrupted the natural rhythms of Morecambe Bay. Margaret, who grew up attuned to the Bay’s tidal cycles, remembers how flood protection barrages, designed to shield Morecambe Bay from storms, unintentionally suffocated mussel beds with mud, forcing the couple to travel farther for fishing grounds. What was once a familiar environment became unsettled, its delicate balance upset by a regulatory logic that overlooked the Bay’s natural cycles. “They said it would take more than 10 years before the barrage altered anything,” Margaret recalls, “but it altered things in six months.” These changes not only affected the local ecology but also led to a deeper cultural loss, like the disappearance of Sandylands Pool, a beloved place where generations of children grew up playing. The loss of such spaces highlights the disjointedness between human timelines and the Bay’s cyclical time, reflecting an ongoing clash between ecological continuity and the pressures of managing coastal catastrophes.

Margaret’s experience highlights the misalignment between traditional fishing practices and the rigid regulations governing Morecambe Bay. As one of the few women licensed to fish with a haaf net, she faces challenges with the ongoing salmon fishing ban, which has lasted for over a decade. While fisherfolk are required to release salmon after catching them, distinguishing between salmon and sea trout in fast-moving waters is difficult and dangerous, especially at night. Margaret criticizes the absurdity of the regulation, pointing out the risks involved and the disconnect between the rules and local knowledge. The restrictions, she argues, are enforced without considering the lived experiences of fisherfolk, sidelining the Bay’s cyclical rhythms and traditional practices in favor of a bureaucratic framework that does not reflect local realities.

This temporal misalignment was never more devastating than in the 2004 cockling disaster, when 23 undocumented Chinese migrant workers drowned after being caught by the incoming tide while harvesting cockles. The tragedy was one not just of illegal labor and exploitation, but of temporal disjunction—people unfamiliar with the local rhythms of tide and terrain, working to an economic clock that disregarded environmental time. The cocklers were operating within a brutally compressed temporality of extraction and desperation, while the Bay moved on its own ancient, unforgiving schedule. The sea offered no warning in bureaucratic terms, only in its own language of rising water and shifting sands. The disaster stands as a grim parable of what happens when human urgency collides with deep tidal time—a misreading of the landscape that proved fatal.

Just as in Morecambe Bay, the Wadden Sea reveals the friction of temporal misalignment between human practices and the changing landscape. A vast network of tidal flats and wetlands, the Wadden Sea has been historically shaped by the rhythm of the tides. These tides create a world of shifting sands, emerging islands, and submerged landscapes that have always demanded a careful attunement to the natural world. Yet, as climate change accelerates and human interventions intensify—particularly the construction of dykes and barriers to protect the land from rising seas—the region is facing an increasingly fragmented temporal experience. Much like Morecambe Bay, the natural processes of erosion and sedimentation, which have long sustained the ecosystem, are now countered by human-made structures that force the landscape into a timeline dictated by the needs of modern society. This disjointed temporal experience produces risks—not only environmental ones like floods and storms, but also quieter risks of lost traditions, ignored knowledge, and ecological misalignment. Despite these challenges, there is resilience as people continue to adapt, reading the water and sky and passing down stories across generations. In these amphibious worlds, where erosion meets memory, flood meets regulation, and disaster meets ritual, time does not simply pass; it accumulates, erodes, and returns.

Figure 21: View from Hallig Oland towards the submerged causeway of the Halligbahn Dagebüll–Oland–Langeneß railway (Schleswig–Holstein Wadden Sea National Park, North Frisia), September 1984. Photograph by Rüdiger Stehn, Kiel, Deutschland.

Figure 21: View from Hallig Oland towards the submerged causeway of the Halligbahn Dagebüll–Oland–Langeneß railway (Schleswig–Holstein Wadden Sea National Park, North Frisia), September 1984. Photograph by Rüdiger Stehn, Kiel, Deutschland.

Photo by Rüdiger Stehn, 1984.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

Along the roadside the Baka People are in between different, often incongruous, times and temporalities. In the forest, seasonal times are marked by plant flowerings, water levels, and the movement of animals. In the forest there are five seasons: Yáká, Sokoyaka (gbíɛ̀mbɔ̀ngɔ̀), Sokoma, Èlàngà, Bi Ebongo (sɔ́kɔ́ mā). All these seasons had natural signals. For instance, one man explained that encountering certain animals coming to wetlands to drink would signal the emergence of Èlàngà, a short dry season between June and August. When cotton on baobab trees starts falling, the rainy season is coming. Living along the roadside, they lack the forests and wetlands lose their temporal resonance. Here the Baka mainly operate according to an agricultural calendar, with seasons for clearing, planting, and harvesting. Different time durations and temporal experiences. In the forest they were always busy. But living by agricultural time often includes times of planning and waiting (siti). For most, time moves slower along the road.

Figure 22: Woman in Assok, Dja-et-Lobo, South Region, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

Figure 22: Woman in Assok, Dja-et-Lobo, South Region, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

© 2025 Blake Ewing. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

We visited the village of Bemba II during Sokoyaka, a season running roughly between January and March. For the Baka here—who now farm a range of crops in the semicleared areas behind their village—when living in the forest, Sokoyaka was a season for hunting and fishing, harvesting honey and wild yams. It was also a time for certain coming-of-age religious initiations during which men had to kill special animals like elephants (yà), giant pangolins (kelepa), and gorillas (ebgobgo). But now—four to five days a week—Sokoyaka is a time for felling and burning trees, and for planting. Conservationists have altered the Baka’s attitude towards hunting protected species, we are told. But nonetheless, due to overhunting and poaching, subsistence hunting requires traveling greater distances, taking more time.

Their agroforestry enterprises also necessitate adapting to the times and temporalities of a broader capitalist world. With agricultural time comes selling time and negotiating time. With no previous experience of money and market economy, Indigenous times had a different sense of value. Payment for time is a new phenomenon, and Bantu farmers, who often hire the Baka as farm laborers, are known to exploit the Baka’s inexperience. The nearby paved highway is also a space of capitalist times on an even bigger scale. Trucks thunder past, day and night, carrying valuable timber—usually moabi or sapele—destined for the port city of Douala. Displaced from the forest, the Baka hear and watch its contents being hauled away, profits made elsewhere. Tree species integral to forest times become matters of delivery time, shipping time, lumbering time, and installation time.

Keywords: erosion, accumulation, acceleration

Link words: cycles, rhythms, structures, seasons, tradition, ruptures, future, adaptation, imaginaries