Introduction

“Nature, the environment and sustainability,” Barbara Adam once wrote, “are not merely matters of space but fundamentally temporal realms, processes and concepts.” This is one of the starting points of the “Wetland Times” virtual exhibition: The material presented here reflects the results of two years of research into the temporal “realms, processes and concepts” present within three wetland spaces, Morecambe Bay (United Kingdom), the northern European Wadden Sea, and the Dja Faunal Reserve (Dja-et-Lobo, southern Cameroon). We frame specific, local wetland “timescapes”—to use another of Adam’s terms—against a backdrop of planetary change, looking at how local times sometimes align with and sometimes push up against those ideas of time (like “deep time” or the idea of the Anthropocene) which have come to dominate global thinking about the environment, biodiversity, and environmental change.

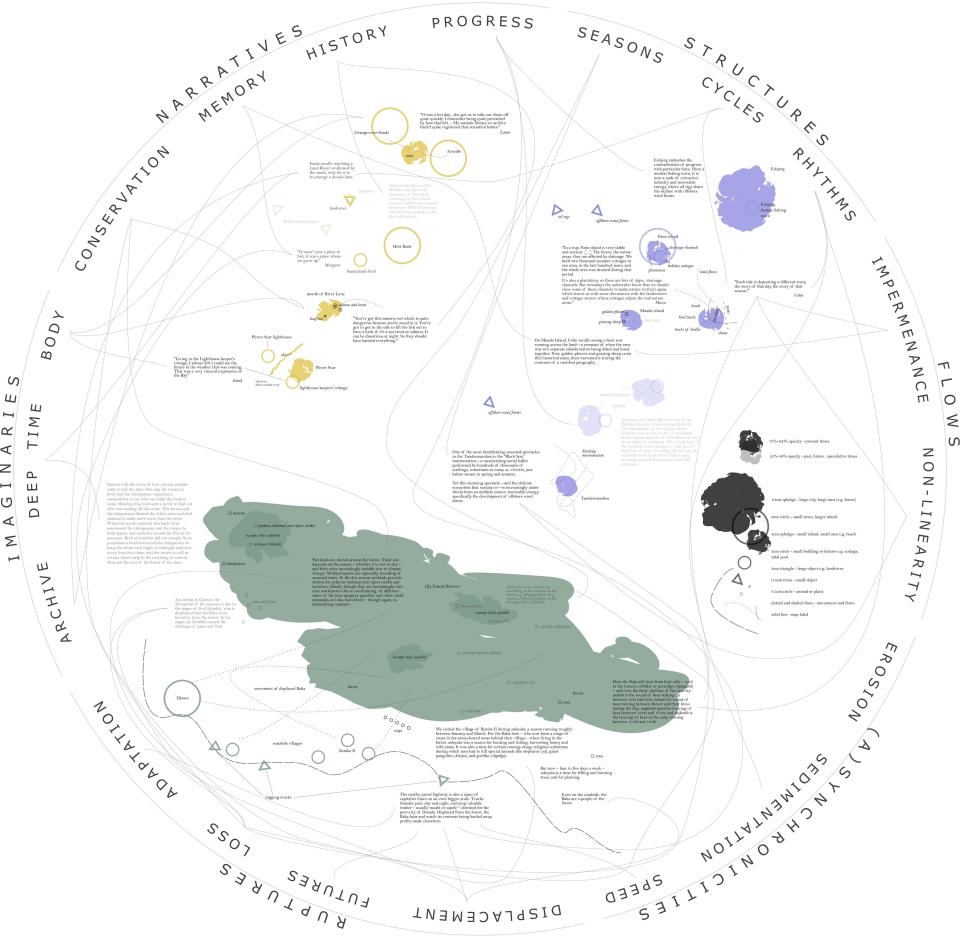

Figure 1: Mapping tool: This virtual wetland times mapping tool serves as an exhibition guide, showing the numerous time stories and voices from across our sites, chapters, and case studies. The data visualization methodology is adapted from the work of Levi Westerfeld and Anne Kelly Knowles by Nicola Thomas.

To read the full text on the graphic, please click on the image twice to open it in a new window and then zoom in.

Figure 1: Mapping tool: This virtual wetland times mapping tool serves as an exhibition guide, showing the numerous time stories and voices from across our sites, chapters, and case studies. The data visualization methodology is adapted from the work of Levi Westerfeld and Anne Kelly Knowles by Nicola Thomas.

To read the full text on the graphic, please click on the image twice to open it in a new window and then zoom in.

© 2025 Nicola Thomas. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

But what, in fact, is a wetland? The term itself emerged as a scientific and policy category in the mid-twentieth century, particularly through international frameworks like the Ramsar Convention, to describe a diverse range of ecologies—from lakes, rivers, and estuaries to marshes, peatlands, mangroves, and tidal flats. Yet this language, while useful in some contexts, risks flattening a much more complex ecological and cultural reality. Local names and classifications—whether fens, bogs, swamps, moors, or the many Indigenous and vernacular terms we encountered—often capture place-specific understandings that are lost when subsumed under the general label of “wetlands.” This question of terminology lies at the heart of our exhibition: The language we use to name and describe wet places shapes how we know, value, and relate to them. In many ways, “wetland” is not simply a category but a compromise, one that reflects tensions between global conservation discourses and the deeply rooted vocabularies of local and Indigenous communities.

In a similar way, we use related terms such as landscape, nature, environment, and ecosystem throughout the exhibition in a flexible and sometimes overlapping manner. While we remain attentive to their distinct histories and connotations, our interest lies less in strict definitions and more in how these terms are mobilized to express temporal relationships. Of these, landscape is particularly significant, as it foregrounds the entanglement of space, time, and lived experience. Concepts from wetland ecology, such as ecotone, describing transitional zones between ecological communities, and hydrosere, the succession of vegetation in wet environments, also remind us that wetlands are not fixed or bounded entities, but inherently dynamic. These scientific terms underscore the temporal and processual nature of wet places, offering valuable insights alongside cultural and experiential understandings.

Figure 2: The Dja River in Dja-et-Lobo, South Region, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

Figure 2: The Dja River in Dja-et-Lobo, South Region, Cameroon. Photograph by Blake Ewing, January 2025.

© 2025 Blake Ewing. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In gathering our data, we spoke to people living and working in each of the case-study sites: to artists and writers who have used creative approaches to think with and through these wetlands; to fisherfolk, hunters, and farmers who know them intimately as a source of food and income; and to conservation practitioners and environmental educators who are passionate about caring for them and communicating their value. We conducted interviews, went on exploratory walks, and asked them to share with us their images and stories.

One of the central tensions that emerged through this process, and that runs throughout the exhibition, is the paradox between the cyclical and rhythmic qualities of wetlands and the fragmented, fractured, and often-unpredictable temporalities they also embody. Wetlands are defined by flows, seasons, and recurrences; yet they are also shaped by rupture, by disjunction, by asynchronous timescapes where pasts, presents, and futures collide or resist alignment. We do not seek to resolve this paradox, but to hold it in view. It reflects the layered and sometimes contradictory temporalities that wetlands, and those who live with and think through them, continually navigate.

From this rich data, a series of overlapping temporal categories and concepts emerged, which here provide the six chapters of this exhibition: Imaginaries, Narratives, Structures, Flows, (A)synchronicities, and Ruptures. These speak to a range of time concepts, from the largest and deepest imaginaries which run (often unacknowledged) beneath temporal experience; through the narrative concepts we use, self-consciously or otherwise, to articulate and aesthetically shape our ideas of time; and the (generally cyclical and rhythmic) structuring frames into which we put time, or via which we understand it—our clocks, calendars, and seasons. The exhibition also explores ideas of temporal flow (duration, tempo, agency) in wetland landscapes; the moments of synchronization and asynchrony within these flows; and ends by examining significant experiences of temporal rupture against the backdrop of planetary change.

Within each chapter, exhibition visitors will find key time concepts listed and linked, in the form of keywords in bold and at the end of the text. These reflect crosscutting ideas that speak to themes across chapters, and they are the product of our interest in how the language(s) of time structures and shapes our thinking about it. Drawing on theories of conceptual history, we explore the contested nature of temporal concepts like progress, history, futurity; of structuring ideas like rhythm or season; and of the instrumentalized time language of conservation, adaptation, and climate change.

How we talk about time, and how we talk about wetland times, matters. Annie Proulx likens the wild array of wetlands around the world to “wallpaper samples, each with its own design and character”—and, we would add, its own time and its own time language(s). This is true in a literal sense: Our research also engaged with speakers of at least seven languages (English, French, Dutch, German, Danish, Frisian, Baka, and Fang). Although the language of this exhibition and its keywords is English, you will notice the presence of these, and other, languages throughout.

Sometimes, our wetland languages emphasize danger and vulnerability, shaping public perception through narratives of treacherous tides and shifting sands, as seen in the legacy of the 2004 Morecambe Bay cockling disaster, when 23 migrant workers tragically drowned due to rapidly rising tides while harvesting cockles. Such fear-driven discourse highlights the unpredictable and hazardous nature of these landscapes, reinforcing the idea that they are to be feared rather than understood. One of our research participants, speaking from Morecambe Bay, calls for a different understanding and language, one that moves beyond sensationalized portrayals and acknowledges the deeper knowledge and respect required to navigate these environments. She advocates for a more reciprocal relationship with wetlands, where language reflects their dynamic, living nature rather than reducing them to sites of peril and vulnerability.

At the same time, the rich vocabulary the Baka People use to describe seasonal and diurnal temporal markers is being eroded as a direct consequence of external political agendas that have displaced them from the forested wetlands they have long inhabited. These wetlands, far from being perceived as dangerous or marginal, are understood by the Baka as spaces of safety and continuity, offering refuge from the real hazards posed by life on the edges of a busy logging road. This contrast between state narratives of progress, which often equate land reclamation and wetland clearance with modernity and development, and the Baka’s lived experience of the wetlands as sites of familiarity, resilience, and belonging, reveals deeper tensions in how time and space are conceptualized. While dominant discourses frame wetlands as obstacles to social advancement—spaces to be drained, ordered, and brought into productivity—the Baka’s temporal vocabularies articulate a different orientation, rooted in ecological rhythms and ancestral connection. What is needed is not the imposition of a new language of progress, but recognition of the temporal knowledge embedded in existing ways of being and relating to place.

Time language shapes the politics and narratives of climate change and biodiversity loss. For one thing, we can understand the concept of the Anthropocene as a new temporal framework that disrupts traditional human progress narratives and foregrounds the urgency of understanding planetary change. Even more pressing, for those who work with wetland landscapes in various capacities, are debates over the temporal baselines of “natural” landscapes in conservation and rewilding efforts: What does it mean to “rewild” an ever-changing landscape? Which parts of human-occupied wetlands are “natural,” and how can attempts to preserve, protect, or conserve these also take account of ideas like history, tradition, and culture? These are some of the questions on which our exhibition aims to shed light.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter