Munich from Below

What Happens Underground?

Anything but Fresh

Why Are There So Many Breweries on the Banks of the Isar?

Beer Gardens Are Drinking Gardens

Food from the Deep

Mushrooms under Goetheplatz

The Queen’s Death Ensures Clean Water

An underground world lurks beneath the pavement, houses, and streets of Munich. Mysterious, dark, dirty—these are words commonly associated with what lies below ground. But there is so much more to subterranean Munich that we don’t know about! Out of sight and unknown to most locals, streams—which were channelized in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—flow underground.

Munich could not exist without its underground world—the city’s lifelines run under these crowded streets. Sewage is cleaned here and residents are supplied with drinking water. Munich is the German metropolis with the highest precipitation level (960 millimeters per year). When a heavy rainfall fills the sewers, water is collected in 13 enormous rainwater-retention and overflow basins. Underground Munich was also important for beer, which was once cooled with ice in storage cellars. Today it is cooled differently, but the underground space offers new opportunities for the future. Will we soon eat food that is grown underground? Munich’s underground is filled with secrets and potential: let’s bring light into the darkness!

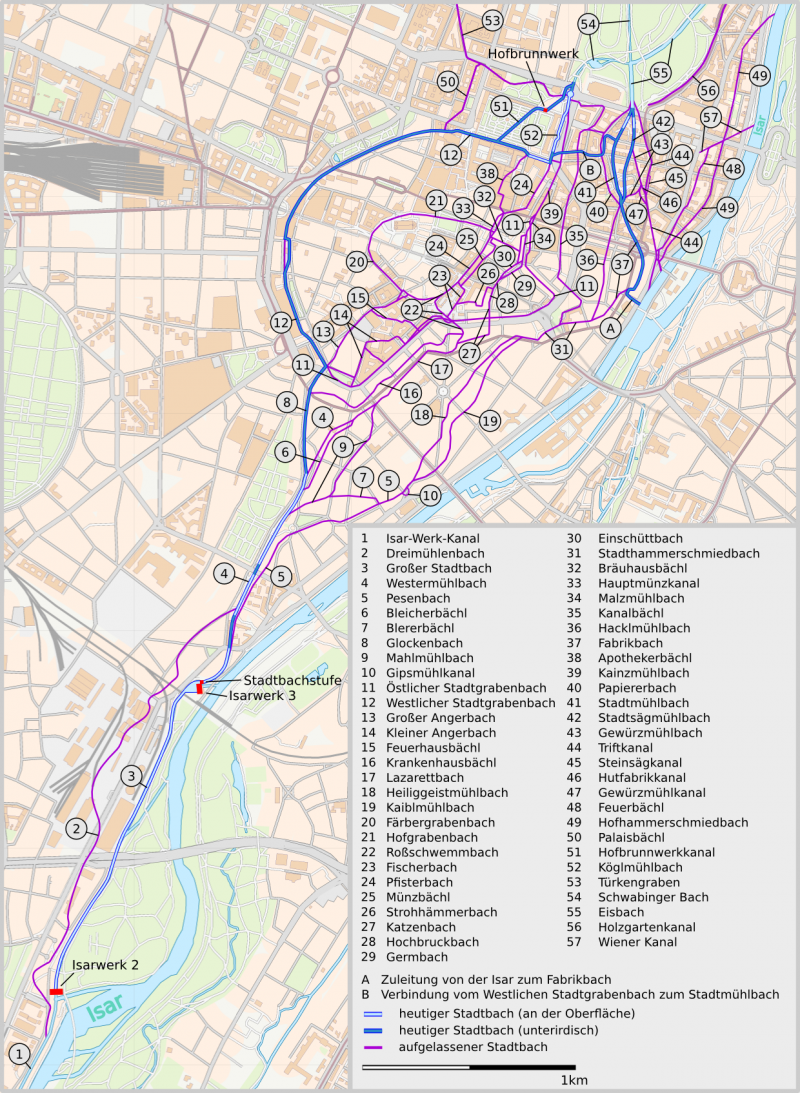

This map shows the course of Munich’s streams that are west of the Isar. The different colors represent whether a stream is on the surface or underground. The ones mapped in dark blue are below ground. The ones in light blue are above ground. And the ones mapped in purple are abandoned streams.

This map shows the course of Munich’s streams that are west of the Isar. The different colors represent whether a stream is on the surface or underground. The ones mapped in dark blue are below ground. The ones in light blue are above ground. And the ones mapped in purple are abandoned streams.

Image licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 on Wikipedia. From: Christine Rädlinger; Stadtarchiv München (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Münchner Stadtbäche. Verlag Franz Schiermeier, München 2004, ISBN 3-9809147-2-0. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%BCnchner_Stadtb%C3%A4che#/media/File:….

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

Anything but Fresh

In the Middle Ages, catastrophic sanitary conditions prevailed in Munich. The city’s inhabitants dumped their garbage on their doorsteps or into the Isar. Only a few meters away, they extracted fresh water from wells. Germs and diseases spread ruthlessly, and epidemics of diseases like cholera and typhus killed thousands. Because beer was produced by boiling and fermenting water, it contained far fewer germs than drinking water. As a result, everyone, even children, drank home-brewed beer. However, because of the poor cooling options, large quantities of beer spoiled, becoming sour. Therefore, it was forbidden to brew beer in the summer. Instead, Munich imported beer from the surrounding areas. Bad Tölz, the largest supplier, was able to cool the beer in natural caves in the tufa, which was optimal, especially in the heat.

Additives were known to increase the shelf life of Munich’s beer: herbs, belladonna, henbane, ox gall, ash, and pitch. However, some of them were toxic. Since the establishment of Munich’s 1487 Purity Law, beer has only been allowed to contain barley, hops, yeast, and water.

Why Are There So Many Breweries on the Banks of the Isar?

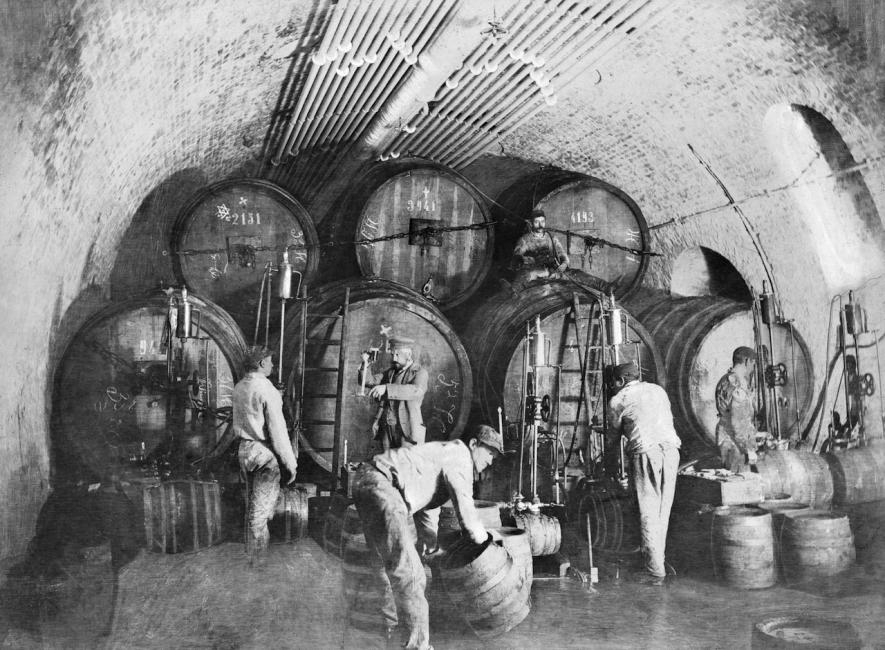

Breweries did not move to the river to brew beer with water from the Isar. The water used to brew beer is tertiary groundwater. The breweries’ own wells draw water from a depth of 150–200 m. The breweries moved to the river to cool their beer in cellars. The cooler the temperature at which the beer was stored, the longer its shelf life. The breweries built deep cellars at the gates of the city, in the sand and gravel pits on the slopes of the Isar. Cooling methods improved steadily. As of 1830, in addition to implementing ventilation systems, breweries also began to use natural ice in their storage cellars. The quality, reputation, and economic success of Munich beer became better and better.

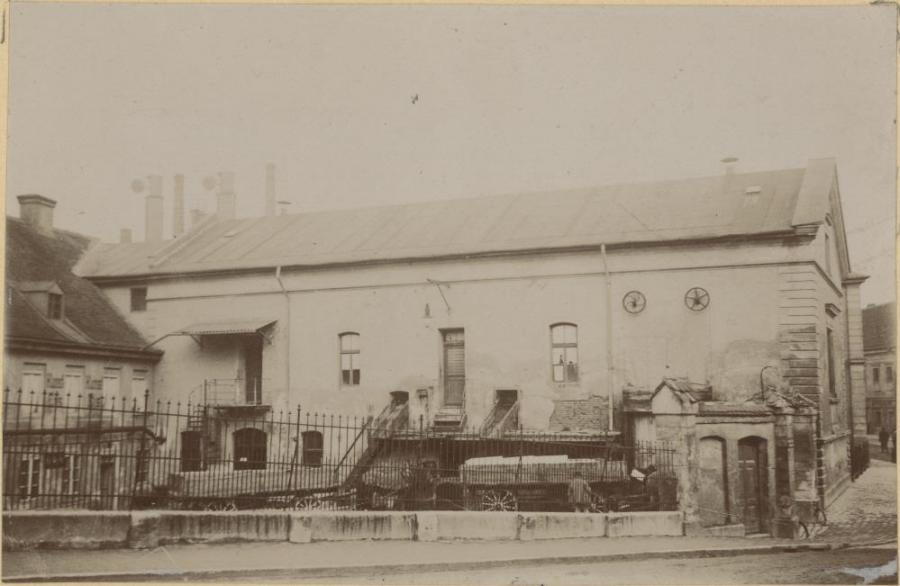

At the end of the nineteenth century, Felix Unsöld founded an ice factory in Munich. The factory was powered by the Stadtmühlbach. Today this stream runs underground. Behind the site of the former factory on Unsöldstraße, the Stadtmühlbach ascends to the surface and continues in the direction of the Eisbach wave. Ice from the factory was used, among other things, by breweries to cool their beer. The first covered artificial ice rink in Europe was located next to the ice factory. The artificial ice rink was a popular meeting spot for Munich residents.

In 1873, the Spaten brewery tested Carl von Linde’s ice machine; but many breweries only adopted it in the 1930s and 1950s. Because of artificial cooling, breweries were no longer reliant on beer cellars and began to move to the city outskirts. The majority of Munich’s beer cellars no longer exist today. After serving as bomb shelters in the Second World War, many were destroyed, demolished, or built over. The beer cellars have since been largely forgotten. Only here and there are they still around, hidden, mostly inaccessible—deep below the cellars of buildings.

The original exhibition features an interactive gallery of images of ice cellars and breweries in Munich. View the images on the following pages.

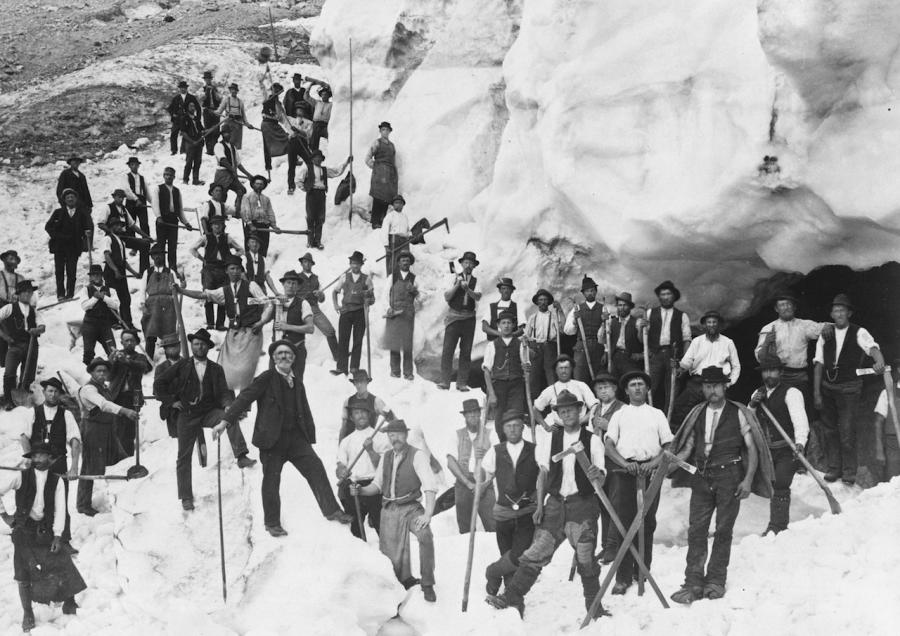

Certain parts of Munich’s beer cellars served as ice cellars. The ice was harvested from nearby lakes and canals, such as the Nymphenburger Canal and the Eisbach.

Photo: Deutsches Museum (used by permission of the copyright holder)

Ice blocks are placed on a wagon in front of the Schmederer ice factory, 1895.

Photo: Stadtarchiv München, DE-1992-FS-NL-KV-0966 (used by permission of the copyright holder)

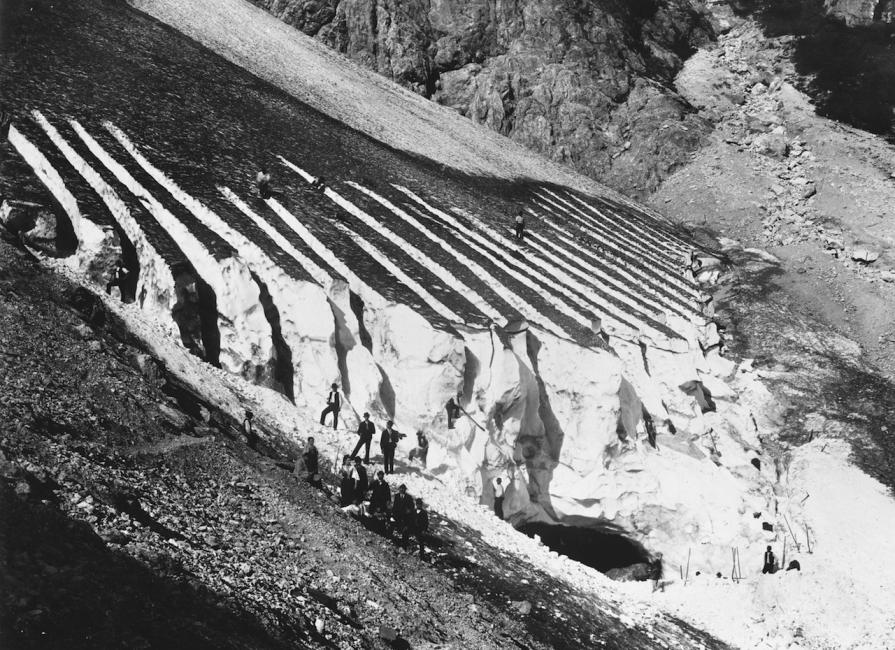

In mild winters, ice for cooling beer cellars was even harvested from the Birnhorn glacier.

Photo: Deutsches Museum (used by permission of the copyright holder)

This pictures shows a group working in the ice field at the Birnhorn glacier. Ice blocks were hauled into the valley using wooden chutes.

Photo: Deutsches Museum (used by permission of the copyright holder)

The ice was then transported to Munich by train.

Photo: Deutsches Museum (used by permission of the copyright holder)

Beer Gardens Are Drinking Gardens

Trees above the beer cellars helped to lower the temperature. Chestnuts were preferred because their thick foliage created large shadows and their shallow roots did not attack the cellar vaults. Another advantage of chestnuts: plant lice did not attack them as they did linden trees, which additionally produce sticky honeydew. Eventually, shady beer gardens were built under the trees.

Munich residents liked to buy their beer directly at the source. The beer gardens soon became serious competition for traditional taverns, so much so that it was prohibited to sell beer by the liter. Citizens and brewers, however, ignored the ban. And as of 1812, only the sale of food was forbidden. As a result, to this day, one can still bring and eat one’s own food in beer gardens.

The original exhibition features and interactive gallery of beer gardens in Munich. View the images on the following pages.

The beer garden at the Augustiner Keller.

Photo: Augustiner Keller

Augustiner Keller

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

A taste of the beer garden culture in Munich. Photo 1 by the Augustiner Keller. This work is used by permission of the copyright holder. Photos 3, 4, and 5 by Lisa Bauer. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Food from the Deep

The exhibition featured the plantCube from agrilution GmbH, Munich, a small greenhouse for growing food at home.

The exhibition featured the plantCube from agrilution GmbH, Munich, a small greenhouse for growing food at home.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Are people today disconnected from their food? The call for local production is getting louder and louder—even in urban environments. Since 2007, more than half of the world’s 7.5 billion people have lived in cities. A third of the Earth’s surface is used for agriculture, but these areas are limited. Food travels longer and longer distances. On average, a head of lettuce travels 1,200 kilometers in Europe—which is the distance from Munich to London. When fruits and vegetables are harvested, they are often still unripe. During transport, not only is a significant amount of CO2 created, but goods often also spoil. In 2050, 70 percent of the world’s 9.7 billion people will live in cities. Food production will have to change. Growing food directly in cities appears to be a reasonable solution to supplying urban populations sustainably. Projects like urban gardening and vertical farming are making this happen.

Can food grown underground sufficiently supply Munich?

According to the latest technology, this is not yet possible. In a city of 1.5 million inhabitants, a lack of space is a real challenge—even underground.

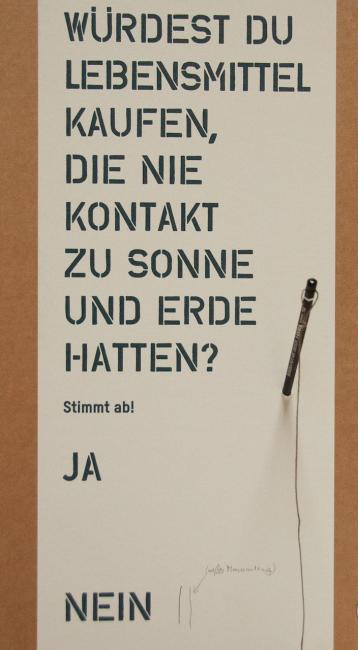

Would you buy groceries that have never had contact with either the sun or the Earth?

The original exhibition features an interactive gallery of underground gardens in Munich. View the images on the following pages.

Growing Underground attempts to provide residents of London with locally grown food.

Photo: Growing Underground (used by permission of the copyright holder)

In London lettuce and herbs are grown using hydroponics in old, disused air-raid shelters. Because a head of lettuce is transported a maximum distance of only 50 kilometers to reach consumers, the quantity of waste decreases.

Photo: Growing Underground (used by permission of the copyright holder)

Today, greenhouses are used to grow food for all of Europe. Here is one example in Almería, Spain.

Photo: Klaus Leidorf (used by permission of the copyright holder)

By cultivating lettuce and herbs on balconies, one can be at least partly self-sufficient in the city.

Photo: Stephanye Zarama-Alvarado (used by permission of the copyright holder)

The plantCube automatically optimizes temperature, irrigation, and lighting for plants. Starting with seeds that are ordered through an app, herbs and lettuce grow in the greenhouse at home. agrilution promises rapid growth, pronounced flavors, and many minerals. Due to the closed system and hydroponic techniques, no pesticides are needed, less water is used, and transportation is no longer required.

Photo: Florin Prună (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License)

Mushrooms under Goetheplatz

After the Second World War, mushrooms were grown underground in an old rail tunnel beneath Goetheplatz. Today the U3/6 line runs through the “mushroom tunnel,” which was built as a section of Munich’s first subway line. The city had already begun to plan a subway in 1905, but the project was discarded and revisited several times before it was realized. The project was revived in the Nazi era. Construction work began in 1938 on Lindwurmstraße. However, in 1941, after only 600 meters, tunnel construction was stopped.

Brown and white button mushrooms need a lot of water, prefer warm temperatures, and do not like direct light. They grow very quickly. In many cities, mushrooms are cultivated underground.

During the war, the subway shaft served as an air-raid shelter, and afterwards as a place for cultivating luxury food: button mushrooms. However, invasive ground water ended mushroom cultivation.

Photo: Stadtarchiv München (RD0774A29)

During the war, the subway shaft served as an air-raid shelter, and afterwards as a place for cultivating luxury food: button mushrooms. However, invasive ground water ended mushroom cultivation.

Photo: Stadtarchiv München (RD0774A29)

Stadtarchiv München

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The Queen’s Death Ensures Clean Water

Max von Pettenkofer brought about a change in Munich’s cleanliness. The doctor found that the recurring cholera outbreaks could be traced back to unhygienic conditions. In order to counteract the causes of the epidemics, he encouraged the idea of a modern sewage system with a waste transport system and the introduction of flush toilets. He also pushed for a supply of drinking water from the Mangfall valley in the Alpine Foreland. He initially encountered strong resistance. The government took action only after the death of Queen Therese of Bavaria. In 1854 she became a victim, along with another 2,935 Munich residents, of a cholera outbreak.

The construction of a sewage system transformed Munich into one of the cleanest cities in Europe. The mortality rate decreased from 42 to 16 people per 1,000 inhabitants. In 1900, 78 percent of the city’s 480,000 residents were connected to the 225-kilometer sewer system. In 2017, that number has increased to 99.9 percent, and the system is 2,500 kilometers long. Pettenkofer’s system still services Munich today. Because it uses differences in altitude in the city, the water can flow across Munich almost without pumps.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images of the Munich sewer system. View the images on the following pages.

These stairs are the entrance to Munich’s underworld. They lead down to the masonry canal that was built in 1912.

All photos are by Lisa Bauer. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

To ensure that wastewater does not flow into the Isar, enormous subterranean basins store excess water.

Curators: Lisa Bauer and Sonja Meinelt

How to Cite: Bauer, Lisa, and Sonja Meinelt. “Munich from Below.” In “Ecopolis München,” edited by L. Sasha Gora. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/8052.