Fröttmaninger Müllberg

Can One Simply Bury the Past?

A Mountain of Waste Arises

It Is Forbidden to Light Candles around Munich’s Oldest Church

A Shepherdess Remains Steadfast

Traveling to the Wind Turbine by Lift

A Matter of Outlook

Near the Allianz Arena, directly next to the highway and the sewage treatment plant, one might expect to find a vacant lot—surely not a recreational area? But the Fröttmaninger Müllberg—a mountain made from waste—is supposed to be exactly that.

From 1954 to 1987, Munich’s household waste was dumped here. Since then, the city has put a lot of effort into transforming this blemish into a natural, green paradise—but has it been successful?

The environmental restoration project has ended, but only intensive maintenance will ensure long-term balance. In 1999, the city of Munich built its first and only wind turbine on top of the hill, as if to give Munich and the Müllberg a greener image. But we wonder: will the past resurface?

The recreational area “Fröttmaninger Berg” is surrounded by the A9 and A99 highways, Freisinger Landstraße, and the Gut Großlappen Purification Plant.

The recreational area “Fröttmaninger Berg” is surrounded by the A9 and A99 highways, Freisinger Landstraße, and the Gut Großlappen Purification Plant.

Maximilian Gabriel (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

A Mountain of Waste Arises

During the first half of the twentieth century Munich had an advanced waste disposal system. But the Second World War left its mark: after the central garbage plant was destroyed in 1944, ditches and pits in the city and on its outskirts served as dumps. The people grew discontent.

The city finally offered an alternative with the construction of a new recycling plant in the north of Munich in 1954—even if it was 10 years later. However, the village of Fröttmaning and its old church had to make way for the plant’s incineration residue.

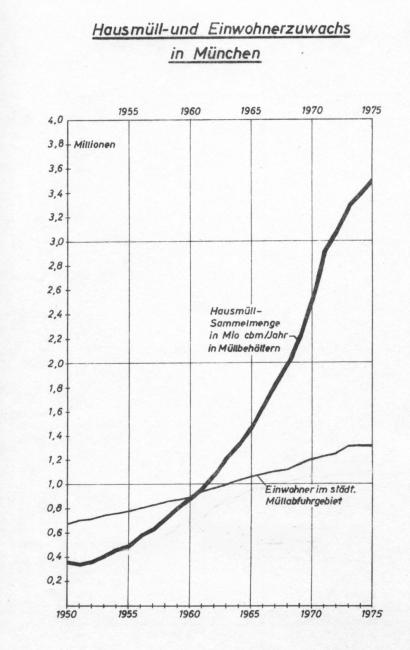

Soon after came economic recovery and consumerism—the amount of waste exploded, triggering a garbage crisis. The new plant could no longer cope with the flood of waste. Unsorted household trash was added to the incineration residue and, with time, grew into an imposing mountain of garbage. The stench and toxins contaminated both air and water.

In 1973, 10 years before the landfill was shut down, Munich’s Department of Urban Landscaping decided to transform the mountain of waste into a recreational area. Today, a reconstruction of the Fröttmaninger Church commemorates the village of Fröttmaning and is located not far from its original location—half sunk in the mountain.

In 2006, Timm Ulrichs created the “Sunken Village” art installation. The reproduction of the church is meant to commemorate the fate of the village of Fröttmaning.

In 2006, Timm Ulrichs created the “Sunken Village” art installation. The reproduction of the church is meant to commemorate the fate of the village of Fröttmaning.

Maximilian Gabriel (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Facts about the Garbage Mountain

- Amount of waste: Around 12 million m³

- Contents: Initially incineration residue, later household and commercial waste, including refrigerators, car tires, chemicals, etc.

- Period the landfill was active: 1954–1987

- Resource potential: The recycling of landfill waste is not yet economically viable. The most recent technologies and current commodity prices make the extraction of new raw materials more favorable.

It Is Forbidden to Light Candles around Munich’s Oldest Church

Highly flammable methane leaks out of the hill. That is why open flames are prohibited on and near the old landfill, and why no candles may be lit at the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche. A process of fermentation in the hill produces the gas. The haphazard storage of garbage that prevailed until the 1980s has made it difficult to seal the dump reliably today. This means toxins can contaminate the groundwater, making it necessary to test the surrounding areas continuously.

First mentioned in 815, the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche is the oldest church in the Munich metropolitan area. It was completely restored in 1980.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery timeline of the Fröttmaninger Müllberg—a mountain made from waste. View the images on the following pages.

1950s

The economic recovery that started in 1950s led to a pronounced increase in the amount of waste.

The new waste recycling plant began operating in 1954. Due to a lack of alternatives, the remnants from the refuse incineration were deposited directly next door.

Photo: Abfallwirtschaftsbetrieb München (used by permission of the copyright holder)

1960s

Within 10 years, Munich’s household waste had tripled. The plant was overloaded and large quantities of unsorted waste ended up in the landfill.

Chart: Abfallwirtschaftsbetrieb München (used by permission of the copyright holder)

1970s

At the beginning of the 1970s, a small lake was built on the top of the summit for chemicals. At the same time, gases from fermentation processes often ignited the whole hill.

Photo: Abfallwirtschaftsbetrieb München (used by permission of the copyright holder)

1980s

Resentment among the population began to grow.

Protests demanded and facilitated change. In the 1980s, the Müllberg closed for good and a new waste management concept was established. From then on: waste prevention before waste incineration before landfills.

Photo: Abfallwirtschaftsbetrieb München (used by permission of the copyright holder)

Today

Today the area is completely restored. The Northern Landfill—not far from the Fröttmaninger Berg—is currently intended to be a repository for incineration residue because waste still cannot be completely recycled nor destroyed.

Photo: Maximilian Gabriel (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License)

A Shepherdess Remains Steadfast

Four local families had to leave their homes by 1954 when the decision was made to build a landfill in Fröttmaning. Yet Barbara Kosmatsch defied the city’s plans. She persisted until 1985—all the while, the garbage grew around her.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images of Fröttmaning village, past and present. View the images on the following pages.

Barbara Kosmatsch’s life on the farm in the former village of Fröttmaning.

Photo: Anneliese Feser (used by permission of the copyright holder)

In 1985, when the city turned off Barbara Kosmatsch’s electricity and water and threatened expropriation, she finally gave in. Kosmatsch was relocated to a replacement farm.

Photo: Anneliese Feser (used by permission of the copyright holder)

The last farmstead in Fröttmaning was demolished. The church is the only building that remains today.

Photo: Anneliese Feser (used by permission of the copyright holder)

Anneliese Feser speaks about her mother-in-law, Barbara Kosmatsch, and her unshakeable sense of home and tradition, which you can listen to (in German).

The original virtual exhibition includes an interview with Anneliese Feser. Listen to the interview online here: https://soundcloud.com/user-724725474/der-mullberg-ein-interview-mit-anneliese-feser#t=0:00.

Traveling to the Wind Turbine by Lift

The Skiarena Association is planning to establish a skiing area to make the Fröttmaninger Mountain more attractive in the future. Numerous ski cannons and groomers will ensure that, even without real snow, a one-minute descent is possible. In 2008, the first test operation took place. But unstable surfaces make it difficult to secure the lifts, and snowmaking is a danger to highway traffic. As a result, at least for the time being, the project has been put on hold and the city of Munich has withdrawn from the plan.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of impressions of the 2008 ski trial run. During the trial run, a rope line, snow groomers, and cannons were used. Photos: Skiresort.de. These works are used with permission of the copyright holder. View the images on the following pages.

Impressions of the 2008 ski trial run. During the trial run, a rope line, snow groomers, and cannons were used. Photos: Skiresort.de. These works are used with permission of the copyright holder.

Facts about the Skiing Area

Slopes: 500 m (300 m easy, 200 m medium)

Difference in altitude: 50 m

Lifts: Two rope lifts in trial operation, one four-chair lift planned

Rating on Skiresort.de: 1.8 out of 5 Stars

A Matter of Outlook

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of impressions of the mountain. View the images on the following pages.

Curators: Maximilian Gabriel and Katharina Ring

How to Cite: Gabriel, Maximilian and Katharina Ring. “Fröttmaninger Müllberg.” In “Ecopolis München,” edited by L. Sasha Gora. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/7967.