Munich and the Isar

The City Makes the River?

A River Makes the City

Isar Quiz

The Renaturalization of the Isar

Habitat: Fish and Birds

For Munich residents, the unpredictable Isar was for a long time one thing above all else: a threat. As a result, from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, the river was “tamed” by means of canals, weirs, and embankments.

Starting in the 1980s, perceptions of the Isar started to change. With its concrete braces, it was hardly attractive. Therefore, the 2000‒2011 Isar Plan made extensive efforts to renaturalize parts of the river within the city limits.

The goals were to improve flood management, create a near-natural river landscape, and to increase the quality of leisure and recreation. The 2013 flood, which affected large parts of Bavaria, proved these renaturalization measures to be successful. Munich was largely spared from the flood’s effects. The modernization of the Sylvenstein Dam and Reservoir, located about 70 kilometers south of the city, also ensured that Munich was protected from the damage.

Today, the newly created river landscape provides benefits to many. Both humans and animals are attracted to the natural beauty of the riverscape: humans go to the Isar to unwind from everyday stress, and birds, fish, and countless microorganisms live there.

But at the same time, this supposed ideal of nature is endangered by the intensive use of the Isar as a recreational area and, thus, the habitat of many species is at risk.

The Weiden Island and visitors at the Isar—from the perspective of a duck.

The Weiden Island and visitors at the Isar—from the perspective of a duck.

Luna Benítez Requena. The Weiden Island and visitors at the Isar, Munich (2017).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

A River Makes the City

The history of Munich could not be told without including the Isar. The river has played an important role since the city was founded in 1158. For a long time, the Isar posed an insurmountable obstacle for salt merchants on their way from the Alps to northern Europe. With the construction of an overpass near what is today the Isar Bridge, Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria, was able to divert the lucrative salt trade to Munich. The revenue from the bridge toll laid the foundation for Munich’s prosperity.

As it was an important waterway, the Isar was crucial in driving the city’s economic development. Wood, stones, and lime were brought to Munich via the Isar to supply the construction boom during the period of promoterism (Gründerzeit). Around 1870, before the expansion of the railway network—which brought about the decline of rafting—Munich had the largest raft port in Europe.

The Isar not only functioned as a transport and trade route but also served as an important source of energy by powering waterwheels. The river is still used to produce renewable energy today.

Isar Quiz

The Museum Island

Throughout history, the “Museum Island,” where the Deutsches Museum is located, has served many uses.

Which of these has it NEVER been used for?

- a) Raft port

- b) Coal storage

- c) Barracks

- d) Train station

The Museum Island served as a docking point for rafts and, in 1870, was considered the largest raft port in Europe. Since charcoal was stored here, locals referred to it as “coal island.” The Bavarian army also had barracks on the island, which were used to protect the richer residents in the capital from the possibility of revolts initiated by rural residents. Although there were plans to build a train station, it was never actually constructed.

Not Much Happens without a Raft

For centuries, rafts were used to transport construction materials to Munich. Around 2,200 tree trunks were required to construct the roof of Munich’s Frauenkirche.

How many rafts were needed to deliver the wood?

- a) about 50

- b) about 150

- c) about 250

- d) more than 500

A view of Munich’s Frauenkirche from Peterskirche Tower. Photo by David Iliff.

A view of Munich’s Frauenkirche from Peterskirche Tower. Photo by David Iliff.

Photo by David Iliff (2006). License: CC-BY-SA 3.0. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Frauenkirche_Munich_-_View_from_Pete…

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany License.

In total, 147 heavily loaded timber rafts were needed to construct the Frauenkirche’s enormous roof. After having transported the cargo, the rafts themselves were disassembled and they too were used as building material.

Passenger Transport on the Isar

Rafts were not only used to transport goods along the Isar; one could also use them to travel to foreign cities.

Which weekly travel connection from Munich existed during the nineteenth century?

- a) Munich – Regensburg

- b) Munich – Salzburg

- c) Munich – Vienna

- d) Munich – Prague

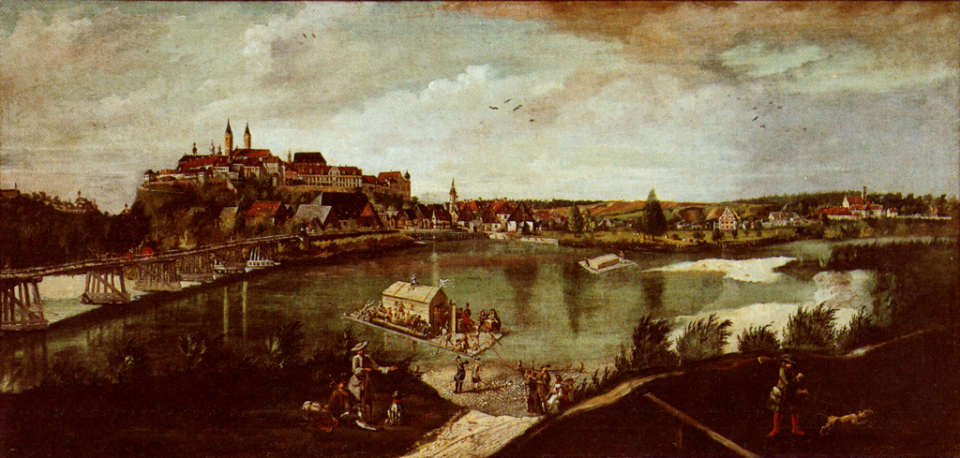

Johann Baptist Deyrer’s 1772 painting is titled “View over Freising from the bridge over the Isar” (Freising von der Isarbrücke aus gesehen) and shows a raft traveling along the Isar.

Johann Baptist Deyrer’s 1772 painting is titled “View over Freising from the bridge over the Isar” (Freising von der Isarbrücke aus gesehen) and shows a raft traveling along the Isar.

Sigmund Benker/Marianne Baumann-Engels: Freising. 1250 Jahre Geistliche Stadt – Ausstellung im Diözesanmuseum und in den historischen Räumen des Dombergs in Freising, 10. Juni bis 19. November 1989, Wewel Verlag, München 1989. ISBN 3-8790-4162-8 , S. 208. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Freising_von_S%C3%BCden_1772.png

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

A raft traveled once a week from Munich to Vienna via Passau and Linz in the mid-nineteenth century. Those who were affluent could afford a cabin; the remaining passengers slept outside on deck. The railway brought about the end of rafting. The last raft made its journey from Munich to Vienna in 1904.

Munich Was Once Called “Little Venice”

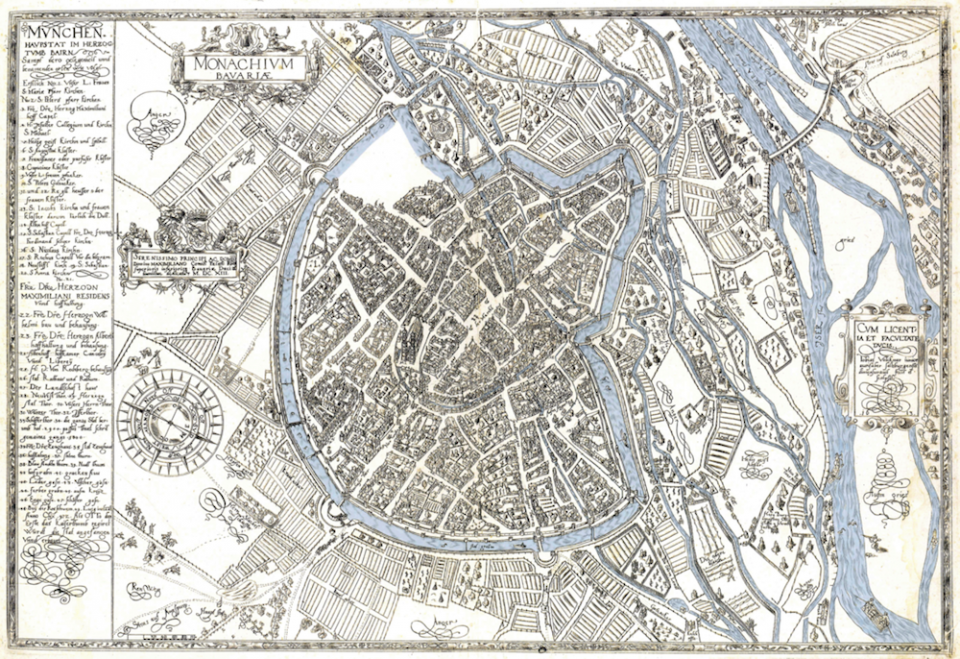

Until the end of the nineteenth century, streams and canals traversed the old town of Munich. This gave the city the nickname “Little Venice.”

Which statements about the streams in Munich are true?

a) They supplied power for timber mills.

b) Some were partially diverted due to the construction of the subway.

c) There are currently plans to reopen some of the built-over streams.

d) The Stadtsägmühlbach still flows under the Parish Church of St. Anna in Lehel.

A 1613 map of Munich by Tobias Volkmer shows the various streams that once ran through the city.

A 1613 map of Munich by Tobias Volkmer shows the various streams that once ran through the city.

A town map of Munich that shows the streams running through the city. Original source: Christine Rädlinger, Geschichte der Münchner Stadtbäche, Herausgegeben vom Stadtarchiv München, Franz Schiermeier Verlag München 2004, ISBN 3980914720. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Volckmer_Munich_1613_streams.png.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

All four statements are correct. With a total length of around 175 kilometers, the urban streams were built over in the nineteenth century and now flow underground. Discussions are currently underway to uncover a city stream under Herzog-Wilhelm-Straße between Sendlinger Tor and Stachus.

Beer from Tölz

Though Munich is today regarded as the beer capital, “barley juice” was already popular here in the eighteenth century. As the saying went, “Whether young or old, man or woman, everyone drinks healthy barley juice.” But why did Munich residents once prefer beer from Tölz to beer from Munich?

- a) Tölzer beer was stronger.

- b) Tölz had stricter beer purity laws.

- c) Tölz had cleaner water.

- d) Tölzer beer was much cheaper.

- e) Beer storage was better in Tölz.

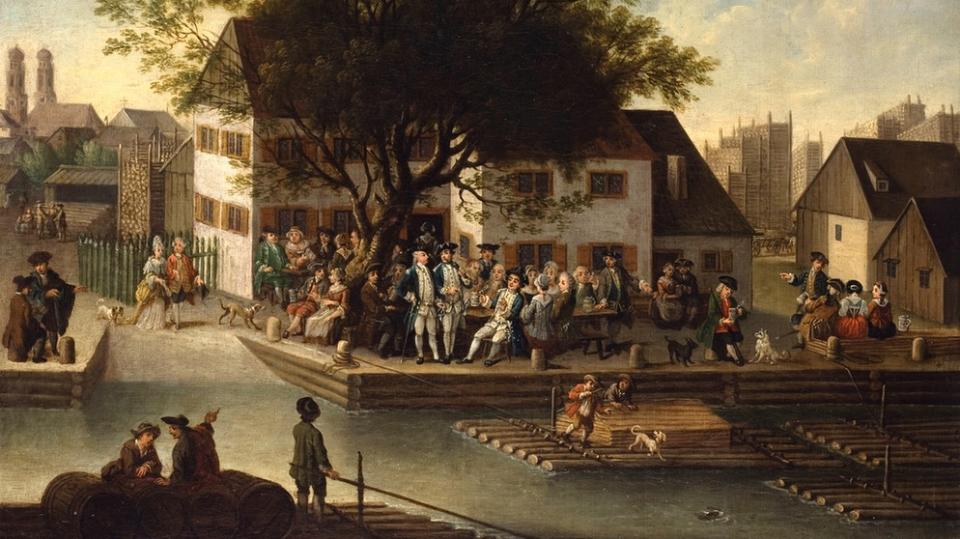

Munich residents preferred Tölzer beer, which was brewed from clear mountain water, because poor sanitary conditions in the city gave Munich’s groundwater a bad reputation. In addition, it was much easier to store beer at a cool temperature in Tölz. Large quantities of beer were brought to Munich on rafts. The tavern “Zum Grünen Baum” was located directly at the raft port, where even King Ludwig sometimes drank with the common folk.

Flood Protection

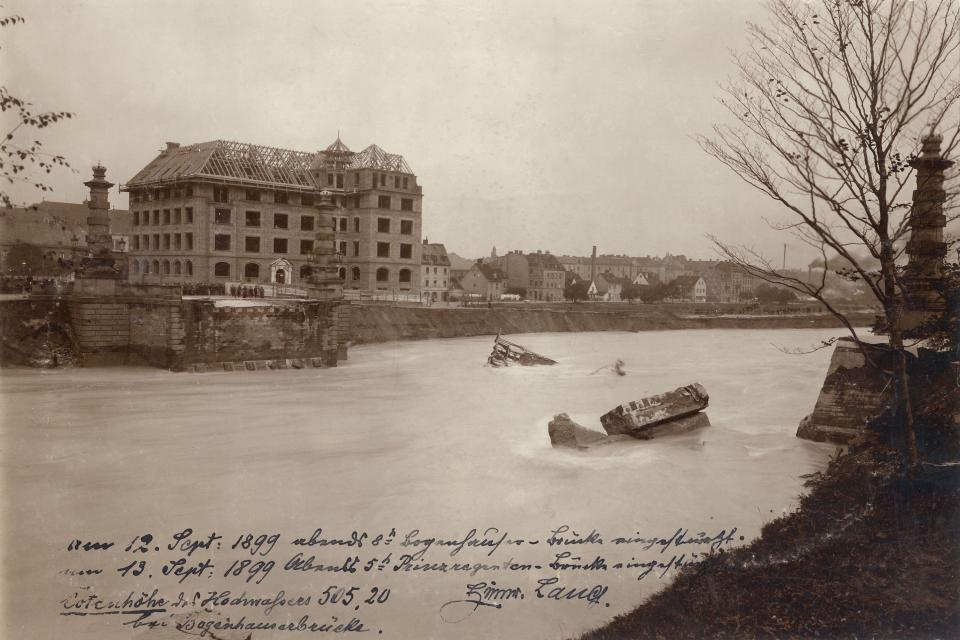

In the past, the Isar was characterized by its mountain river torrents. One of Munich’s largest natural disasters was the 1899 Isar flood, during which the bridges that predate today’s Ludwig and Max-Josef Bridges collapsed. Since then, bridges in Munich have been constructed only from stone.

Which measures have been implemented to improve flood management?

- a) The construction and modernization of the Sylvenstein Reservoir

- b) The renaturalization of the Isar

- c) The straightening of the river

- d) The expansion of hydropower stations

The Sylvenstein Reservoir south of Lenggries is the most important protection measure to prevent flooding in Munich. Built in 1959, it has been expanded several times. Thanks to the reservoir, Munich was spared from Bavaria’s “flood of the century” in 2013. The renaturalization of the Isar also serves to prevent flooding; however, efforts to straighten the river course have increased the risk. Hydropower plants do not have any direct influence on floods.

The Renaturalization of the Isar

In 2011, the renaturalization of the Isar was completed. The numbers on this map correspond with the text in this section.

This map was designed by Alfred Küng and Katharina Kuhlmann. It is based on a map from ‘Neues Leben für die Isar’ by Christine Rädlinger and published by Franz Schiermeier Verlag München (2012).

In 2011, the renaturalization of the Isar was completed. The numbers on this map correspond with the text in this section.

This map was designed by Alfred Küng and Katharina Kuhlmann. It is based on a map from ‘Neues Leben für die Isar’ by Christine Rädlinger and published by Franz Schiermeier Verlag München (2012).

Alfred Küng and Katharina Kuhlmann

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

1. Water Quality

The water quality of the Isar is excellent, to the extent that it has been classified as suitable for bathing. Purification plants ensure the appropriate water quality by treating the water with ultraviolet radiation. Since 2001, this method has been used to remove microorganisms in the water that are harmful to humans, such as coliform bacteria. However, after a heavy rainfall, it is still possible for unfiltered water to enter the Isar.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images of flasks that demonstrate how the water quality of the Isar has changed since purification plants were introduced in 1970s. View the images on the following pages.

Before 1970

There were no purification plants before 1970.

Human feces, food scraps and the like, all contaminated the water.

All photos are by Luna Benítez Requena. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

From 1970

Purification plants were introduced in the 1970s.

The plants mechanically clean the wastewater.

These flasks demonstrate how the water quality of the Isar has changed since purification plants were introduced in 1970s.

2. Ecological Water Conditions

The ecological state of rivers, lakes, and groundwater in Munich is evaluated according to the EU Water Framework Directive Innovation Program. The condition of the water in the Isar is measured between Großhesseloher Bridge and Marienklausen Bridge. Four groups of organisms are assessed: small invertebrates (macrozoobenthos), aquatic plants and stationary algae (macrophytes), fish, and drifting algae (phytoplankton). Because the number of fish species and juvenile fish in Munich is too low, the ecological condition of the Isar only ranks as “moderate.”

3. A Wall for the Dikes

Dike renovation was a central step in the renaturalization of the Isar. However, it was important not to damage the valuable rows of trees growing on the dikes. If their roots separated from the ground during a flood, this would create weak points that would compromise the stability of the dikes. A complex process brought about the solution: a cement-bentonite wall inside of the dikes effectively protected them from damage during floods, and allowed the trees to remain untouched during the renovation.

4. The White-throated Dipper

The white-throated dipper is the bird that has probably benefited most from renaturalization—it finds more food than ever before along the new shores of the Isar. However, the river’s popularity means that undisturbed nesting sites are rare, and environmentalists have set up hidden nesting sites to protect the dipper from disturbances when breeding.

5. The Last, Old Fish Ladder

From the Flauchersteg Bridge, one can still see it today: the last of the old fish ladders in the Isar. Before renaturalization, there were 17 fish ladders, but many fish were unable to use them: for large species of fish, such as Danube salmon, they were too small. And for small fish or poor swimmers, such as loaches and European bullheads, the 30-centimeter-high passes were far too steep. As a result, they could no longer reach their feeding and spawning grounds.

The last of the old fish ladders in the Isar as seen from the Flauchersteg Bridge.

The last of the old fish ladders in the Isar as seen from the Flauchersteg Bridge.

Luna Benítez Requena (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

6. Dead Deadwood?

The deadwood along the banks of the Isar is full of life. Dead tree trunks and branches are teeming with activity, from insect larvae to small invertebrates, such as crabs, mussels, snails, and worms. In addition, deadwood stabilizes the renaturalized shoreline. Gravel actively anchors large trunks, ensuring they no longer drift away during floods. Deadwood in shallow water provides fish, such as schneider, minnow, European chub, brown trout, common barbel, and Danube salmon, with food and shelter alike.

An example of deadwood along the banks of the Isar.

An example of deadwood along the banks of the Isar.

Luna Benítez Requena

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

7. Nutrients along the Meadow Banks

New gravel banks broaden and flatten the Isar’s shore, causing more nutrients, such as nitrates and phosphates, to dissolve in the water. These broader banks also retain more nutrients. However, the sparse grassland that was planted during renaturalization requires very few nutrients, making it out of place in this ecosystem. Many dog owners walk along the renaturalized Isar, leaving behind dog excrement, which additionally increases nutrient input.

8. Place of Refuge

The shallow areas that run through the Weiden Island provide particularly favorable conditions for bottom-dwelling fish like streber. Although this fish is rare in the Danube catchment area, last year one thousand streber were marooned on the Weiden Island. Another count will soon take place. An (unsuccessful) attempt was also made to reintroduce German tamarisk here—a type of bush that has not been found along the Isar since the 1950s. However, the bushes did not survive for long. People also follow the path through the water along the desolate Weiden Island—could this prevent it from being a place of refuge for animals and plants?

The Weiden Island from the perspective of a fish.

The Weiden Island from the perspective of a fish.

Luna Benítez Requena (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

9. Small Isar—Lots of Water

For a long time the Small Isar biotope was endangered because not enough water could flow into it. Thanks to an arm extension measuring two hundred meters, more water can now reach the Small Isar, improving the habitat for fish and microorganisms.

A New Life for the Isar?

“Various investigations have revealed that in addition to the reappearance of animal and plant species that were common to the area prior to renaturalization, new species typical to the wild river landscape of the Isar have been able to settle there. True to the motto of the Isar Plan: a new life for the Isar.”

Department for Health and Environment of the State Capital of Munich

“Renaturalization has had many positive effects, but if you look at it purely from the perspective of terrestrial vegetation, it has not been completely successful. Species that are specialized for living in wild rivers and river-born alpines, for example, do not have a chance. Furthermore, where the Isar is somewhat wilder, such as at the Small Isar, the more powerful water supply has led to an increased output of gravel and a new hydrodynamic so that field vegetation, which is protected by the Fauna-Flora-Habitat Guidelines, could be lost there. For the vegetation along the riverbanks, renaturalization has had more or less a neutral effect; but the flora and fauna of the wild river landscape do not necessarily benefit. Also, the German tamarisk that we planted has dried up or been trampled upon, and is now endangered.”

Prof. Dr. Johannes Kollmann, Ecological Restoration, Technical University of Munich

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images the exhibition table that tells the story of the renaturalization of the Isar. Exhibition table and photographs by Luna Benítez Requena and installation photos by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This exhibition table tells the story of the renaturalization of the Isar. Exhibition table and photographs by Luna Benítez Requena and installation photos by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Habitat: Fish and Birds

A Death Trap for Fish

Hydropower plants, where death looms, present an obstacle for the fish of the Isar. The structures block fish on their way upstream to their spawning grounds. Fish ladders, which were implemented as an alternative way upstream, are often not used by the fish— they find the ladders unfamiliar and, in part, impassable. On their way downstream, the fish prefer those zones with the greatest flow rates, which lead directly to the turbines of the hydropower plants. The fish emerge either heavily injured, or completely sliced and diced.

Safe Nests?

Some bird species, such as the little ringed plover that is endangered in Bavaria, breed directly in the gravel. The new gravel banks of the Isar could be a possible habitat for these birds. Nevertheless, according to experts’ statements, the bird has not settled here. There are simply too many destructive elements. Furthermore, the areas along the Isar are not particularly safe for the offspring of these “bush breeders.” The brush cannot stop inquisitive dogs, which frighten off the breeding birds. And the brush that has been cleared in an effort to prevent floods has displaced them. The birds at the Isar also suffer from the pollution of their habitats by humans. On a mild summer weekend in 2016, around four tonnes of garbage was recorded on the Flaucher Island alone.

Under Water

Fish that spawn in gravel, such as the common barbel, common nase, and trout, spawn in the rocky riverbed of the Isar. Even if these fish do not spawn in the summer months, visitors seeking to relax at the Isar should keep the fish in mind. Summer bathers push the fry and juveniles of koppe and loach from the shallows to the deeper waters, where predators lie in wait. Bathers also stir up sediment that clouds the water, which distresses the fish that prefer clear water.

During the summer, many people barbecue, party, and smoke at the Isar. Charcoal soaked in chemical lighter fluid is carelessly disposed of, which pollutes the water and can be deadly for fish. Cigarette butts that land in the water are especially harmful to the Isar’s residents. The substances that cigarette filters contain and release into the water—neurotoxins such as nicotine, arsenic, and lead, as well as toxins like copper, chromium, and cadmium—can kill fish and microorganisms.

According to a study conducted by San Diego State University, a single cigarette butt can contaminate 40–60 liters of water.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of a diorama in the exhibition that depicts birds and fish found in and around the Isar in Munich. Diorama by Elisa Hanusch and photos by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

A diorama in the exhibition depicts birds and fish found in and around the Isar in Munich. Diorama by Elisa Hanusch and photos by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

HOUSE RULES

- Please keep to where you are allowed to go. We need a refuge where we are not disturbed by people or dogs! Here we can lay our eggs, rest, and take a break from the city noise.

- Please pay attention to your four-legged friends, especially from 1 March to 30 September, so that we can take care of our young undisturbed! Please do not let them wander through the bushes.

- Phew—that stinks! Please barbecue only in the designated areas because so much smoke and so many smells are no good for us sensitive animals! And then please dispose of the grill charcoal in the containers specifically placed there for charcoal.

- Please clean up your garbage! That is why there are garbage bins. If they are full, just put your garbage next to them. If you like the Isar so much, please leave it as you found it. Then we will all benefit.

- Many pennies make a dollar. Please also dispose of your bottle caps and especially your toxic cigarette butts properly. A small, portable ashtray helps with this and saves us a lot of trouble.

- Do you also throw bottles around in your apartment? No? Then please do not do this in our home either! In this case, broken glass doesn’t bring us any luck.

- Plastic is not fantastic. Please clean it up, or simply bring your food in reusable containers and leave your trash at home.

- Use the toilets to do your business, so that our home stays clean!

Curators: Luna Benítez Requena, Elisa Hanusch, and Johannes Summer

How to Cite: Benítez Requena, Luna, Elisa Hanusch, and Johannes Summer. “Munich and the Isar.” In “Ecopolis München,” edited by L. Sasha Gora. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/8050.