Across the globe, the enormous demand for renewable water resources, especially for agriculture, is putting freshwater ecosystems under growing strain. However, the distribution of freshwater is unequal, with pockets of scarcity and overconsumption. “Virtual water” has been heralded as an answer to this inequality. Virtual water refers to all the freshwater that is consumed or transformed in order to produce commodities or services at their point of origin, and which is then traded across international lines embedded in these commodities or services. According to its proponents, this offers a way to quantify water and move it across international boundaries by allowing water-scarce countries to effectively import freshwater through trade in commodities.

Photograph by Ian D. Keating. Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

John Anthony Allan, a British geographer and an emeritus professor at King’s College London, invented the concept of virtual water in 1993. In a conference paper, Allan argued that water should be seen as liquid capital.

How then is it possible to argue that there are substitutes for water? The answer is partly that they have already been found … [Many countries] either have sufficient water or they do not need it since they can substitute oil revenues to purchase food which cannot be produced at home because of water shortages.

—John Anthony Allan

He argued that countries adopting virtual water as an international trade and natural resource management philosophy would receive immense economic benefits, as food often costs less to import than to grow domestically. Moreover, he asserted that virtual water would lead to world peace by preventing resource-based conflict. He supported his theoretical framework with charts plotting estimates of food imports, trade balances, and water deficits for countries around the world. At precisely the time when Western governments were shifting from national, “command and control” environmental regulations to neoliberal, market-based forms of global environmental governance, virtual water offered a conceptual framework for seeing water itself as an internationally traded commodity.

Complex computation and data visualization tools are used by researchers attempting to identity and quantify virtual water linkages.

Complex computation and data visualization tools are used by researchers attempting to identity and quantify virtual water linkages.

Image created by Thomas Breu, Christoph Bader, Peter Messerli, Andreas Heinimann, Stephan Rist, and Sandra Eckert. Click here to view PLOSONE source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

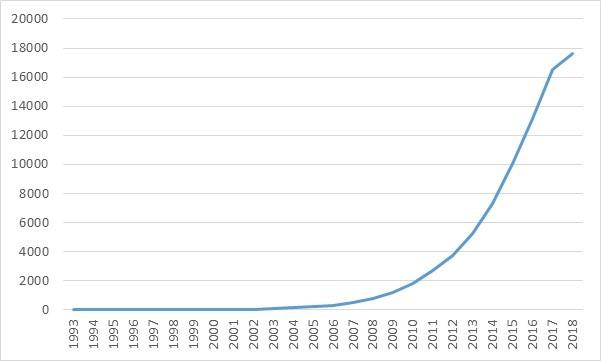

It took more than a decade for virtual water to gain traction in the research community, however. On 19 March 2008, Allan won the Stockholm International Water Institute’s prestigious Stockholm Water Prize, an industry-sponsored award that credited virtual water for raising awareness of the relationships between crop production, economics, and political processes. The publication and citation of journal articles studying virtual water have increased exponentially since Allan won the award. The influence of prestigious awards on the uptake of scientific ideas is an understudied phenomenon in environmental history and the history of science. Allan and his virtual water framework appear to have greatly benefited from the Stockholm Water Prize.

Technological advances also enabled the uptake of virtual water. The concept has come a long way since Allan’s original handmade table of estimated surpluses and deficits. Especially at global scales, virtual water would not have been possible without the rapid increase and dissemination in computer programming, imaging technology, and modeling. Grid assessments of monthly runoff, flows, and other hydrological elements have been simulated electronically. Complex computer models have been adapted from the modeling of neural networks and genetic algorithms. Advances in computer-aided modeling, the imprimatur of a prestigious industry prize, and the historical paradigm of neoliberal environmental management have cleared the way for widespread acceptance of virtual water.

The cumulative sum of academic journal articles in the Web of Science Database written about “virtual water” cited by other articles from 1993 through 2017 totals 17,635

The cumulative sum of academic journal articles in the Web of Science Database written about “virtual water” cited by other articles from 1993 through 2017 totals 17,635

Graph created by Kaitlin Stack Whitney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Yet as virtual water has increased in usage and complexity, it is worth noting what is missing. Neither Allan, nor the Stockholm International Water Institute prize committee, mention ecological understandings of water. Virtual water nationalizes water resources in an effort to map water along national borders and international trade routes, but the water basins of the world do not map onto administrative borders. Further, virtual water only counts water in products crossing administrative boundaries, not watersheds. Virtual water is a quintessentially neoliberal form of water modeling—reducing global water flows to commodity flows in hopes of using trade to solve water crises. Even watersheds have become markets.

In the past three decades, there has been a major shift toward quantifying nature in the service of neoliberal forms of environmental management, through concepts like virtual water (or wetlands banking, carbon offsets, and “ecosystem services” generally). This quantification process presents its own problems, as it is unclear who gets to determine which numbers are “correct” and how they should be determined. Among academic researchers, there is a wide range of opinion on how to measure and interpret virtual water. Even if there could be agreement on how to properly quantify water, this would not solve the complex problem of managing actual freshwater resources globally. Quantification here plays a dual neoliberal role conceptually: it both renders water calculable and manipulable through international trade, and attempts to depoliticize that trade by making water management a technical matter of accounting using “objective” numbers.

The annual number of academic journal articles in the Web of Science Database written about “virtual water” from 1993 and 2017. In total, the sum is 843 articles to date

The annual number of academic journal articles in the Web of Science Database written about “virtual water” from 1993 and 2017. In total, the sum is 843 articles to date

Graph created by Kaitlin Stack Whitney

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Ultimately, virtual water blurs distinctions between policy and science, models and reality. It is paradoxically an oversimplification of global water flows that is still so complex it requires advanced modeling techniques and technology. At the same time, it is an oversimplification of the political economy of global trade, that cannot be instituted given the realities of international trade and politics. With the invention of virtual water, subsequently endorsed by an industry prize, Allan turned water into liquid capital, a fungible commodity to optimize through international trade, stripped of ecological and political context. While prizes and neoliberal trends in environmental management can go a long way towards furthering the intellectual acceptance of concepts like “virtual water,” it remains unclear whether such concepts could, or should, be implemented in the hydropolitical world.

How to cite

Stack Whitney, Kaitlin, and Kristoffer Whitney. “John Anthony Allan’s ‘Virtual Water’: Natural Resources Management in the Wake of Neoliberalism.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2018), no. 11. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8316.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2018 Kaitlin Stack Whitney and Kristoffer Whitney

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Allan, John Anthony. “Fortunately There are Substitutes for Water, Otherwise our Hydro-Political Futures Would be Impossible.” In Priorities for Water Resources Allocation and Management, 13–26. London: Overseas Development Administration, 1993.

- Barnes, Jessica, and Samer Alatout, eds. “Water Worlds.” Special issue, Social Studies of Science 42, no. 4 (2012).

- Gunningham, Neil. “Environment Law, Regulation and Governance: Shifting Architectures.” Journal of Environmental Law 21, no. 2 (2009): 179–212.

- Lincoln, Anne E., Stephanie Pincus, Janet Bandows Koster, and Phoebe S. Leboy. “The Matilda Effect in Science: Awards and Prizes in the US, 1990s and 2000s.” Social Studies of Science 42, no. 2 (2012): 307–20.

- McCarthy, James, and Scott Prudham. “Neoliberal Nature and the Nature of Neoliberalism.” Geoforum 35 (2004): 275–83.

- Porter, Theodore. Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Whitney, Kristoffer, and Melanie A. Kiechle, eds. “Counting on Nature.” Special issue, Science as Culture 26, no. 1 (2017).