The 1958 US–UK Mutual Defense Agreement instigated nearly forty years of cooperative nuclear weapons testing, which only eventually ceased due to the implementation of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CNTBT) in 1996. However, prior to 1958, the Grapple H-bomb nuclear test series demonstrated that the United Kingdom had sufficient technological collateral and a hitherto unrecognized influence upon the Cold War dynamic. Whilst the Grapple series were a bombastic display of British military prowess, there is a paradoxically human element to nuclear weapons testing. Here, we consider the day-to-day experiences of the soldiers who travelled to Christmas Island to test the bomb.

Due to the necessarily covert nature of the United Kingdom’s nuclear program, many of the soldiers were unaware of the political significance of their work. There was also little prior warning before deployment, one veteran said, “I was notified a week in advance. I was told to go to London airport with my entire kit bag … we were men with overcoats and gloves, travelling to a tropical island.” The soldiers were travelling prior to the advent of affordable commercial flight, and being posted to Christmas Island was often their first opportunity venture abroad. Most travelled by commercial aircraft to the United States and Hawaii, then on to Christmas Island. However, the Royal Engineers commissioned a commercial cruise liner to deploy their regiment, which also included the families of currently posted soldiers for a tropical holiday. Whether this was a compassionate gesture or a publicity stunt is subject to debate.

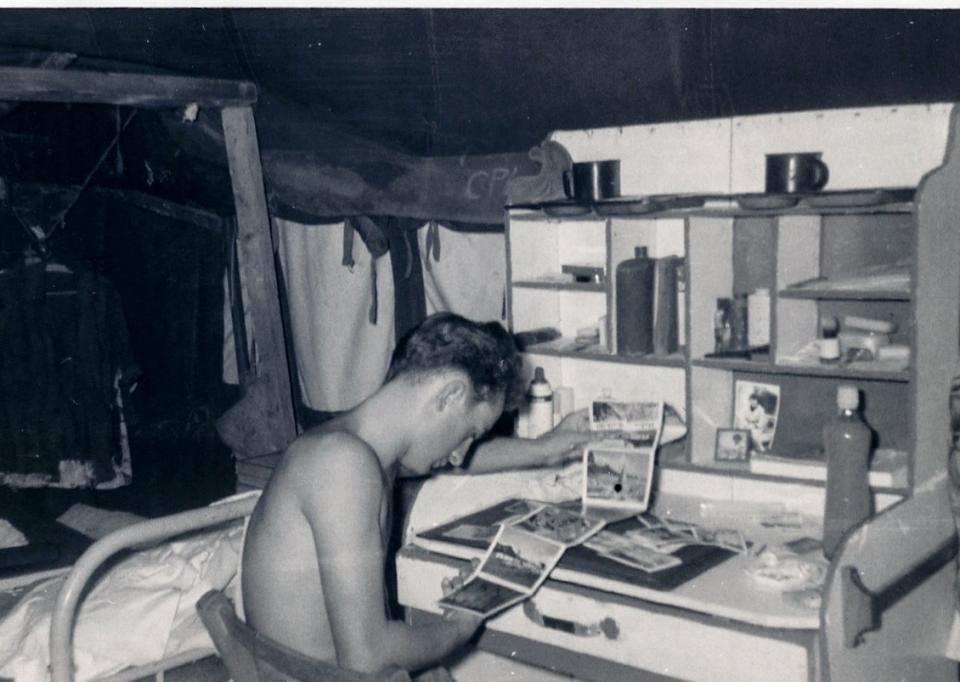

Upon arrival, the men initially bunked up in three-berth transit tents before relocating to larger facilities at base camp. Accommodation was simple and basic: the men slept on camp beds and made their own furniture in their spare time. North camp had showers; however, South camp did not, and therefore saltwater-lathering soap was provided for men to wash in the sea. The local wildlife intruded upon camp life, and whilst DDT was sprayed daily to protect the soldiers from malarial mosquitos, little could be done to prevent large land crabs from crawling into the soldiers’ tents at night. The men resorted to propping their beds up on jerry cans to reduce the likelihood of waking to find a crab nestled in their bedclothes. It was also a military offence to kill a land crab, as they were useful scavengers on the island. A veteran said that the local Fijians “… called [the crabs] Laro, and they ate them.” However, the soldiers did not, he reported. Otherwise, both soldiers and the Fijian camp community ate a diet of traditional British food and regional fruit and vegetables, including bananas and sweet potatoes. Food was served within the mess tent on compartmentalized metal trays, with depressed sections for main course and dessert. One veteran described the experience of mealtime to me, saying “… if you weren’t careful with your tray, your custard and gravy would escape and combine.” In addition to the mess tent, there was a church, an open-air cinema, and two “matronly” ladies of the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service who organized activities and games for the soldiers. Whilst the officers drank Grapple Slings, the young soldiers supplemented warm beer with moonshine brewed in gallon jars buried in the sand beneath their tents. The men went swimming, walking, and fishing, enjoying the idyllic tropical environment. However, this beautiful place was peppered with a light dusting of fallout after each test.

There was limited interaction between the soldiers and the Fijian community, although they performed general labor in camp, including emptying the Elsans (chemical toilets). Fijians were provided with multiple helpings of food whilst working, although whether this was due to undertaking more laborious work or to improve community relations is unclear. Some of the soldiers bought souvenirs and trinkets from the local community to take home to their families. There was a myth of the Islander Wife, the woman who fell in love with a soldier and left to marry him in the UK. Despite this, the communities remained separate.

The H-bombs were detonated every three months. The soldiers were sent outside and instructed to cover their eyes with their fists, and to face away from the blast. The health and safety officer said they would receive no more radiation than from an x-ray. Then business resumed as usual: the army cooks returned to preparing next meal, the aircraftsmen resumed vehicle maintenance. However, each nuclear blast produced an environmental legacy of radionuclides that were scattered across the land and sea by the wind.

Since gaining independence from the United Kingdom on 12 July 1979, Christmas Island is now known as the Republic of Kiribati. Changes have occurred on this tiny archipelago; exports of copra (dried coconut pulp) have grown, and it has become a destination for ecotourism. Whilst the atoll ecology is flourishing, radioactivity continues to permeate the environment. The Fijians and the young soldiers who lived and worked on Christmas Island cannot disregard their simultaneously mundane and unearthly experiences of paradise.

How to cite

Alexis-Martin, Becky. “‘It was a Blast!’—Camp Life on Christmas Island, 1956–1958.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2016), no. 19. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7693.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2016 Becky Alexis-Martin

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Hecht, Gabrielle. Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

- Hogg, Jonathan. “‘The Family that Feared Tomorrow’: British Nuclear Culture and Individual Experience in the Late 1950s.” The British Journal for the History of Science 45, no. 4 (2012): 535–49.

- Holdstock, Douglas, and Frank Barnaby. The British Nuclear Weapons Programme, 1952–2002. London: Frank Cass and Company Limited, 2003.

- Jones, Peter. “Overview of History of UK Strategic Weapons.” History of the UK Strategic Deterrent: Proceedings of the Royal Aeronautical Society Symposium, 17 March 1999, 2.1–2.16.

- Maclellan, Nic. “The Nuclear Age in the Pacific Islands.” The Contemporary Pacific 17, no. 2 (2005): 363–72.

- Oulton, Wilfrid Ewart. Christmas Island Cracker: An Account of the Planning and Execution of the British Thermo-Nuclear Bomb Tests, 1957. London: Thomas Harmsworth Publishing, 1987.

- Log in to post comments

- Print page to PDF