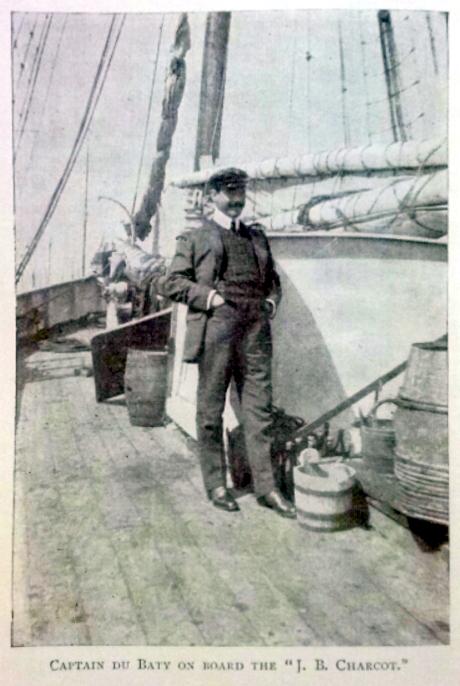

Captain du Baty on board the J. B. Charcot, from his book 15,000 Miles in a Ketch.

Captain du Baty on board the J. B. Charcot, from his book 15,000 Miles in a Ketch.

Unknown photographer, September 1907. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1908, Raymond Rallier du Baty, his brother Henry, and a four-man crew sailed the tiny ketch J.B. Charcot from Boulogne to the Kerguelen Islands, a subantarctic archipelago in the far southern Indian Ocean. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Kerguelen Islands, claimed by France since 1763, were an outpost of the marine mammal oil industry. Whaling ships anchored at the islands for months at a time to repair, resupply, and supplement their cargo with elephant seal oil. The voyage of the J.B. Charcot was one of several attempts by private French citizens to take part in a primarily American, British, and Norwegian industry that exploited “French” resources. When he returned to France, Raymond Rallier du Baty spread the story of his adventure far and wide, publishing the story of his adventure in English as 15,000 Miles in a Ketch in 1912. Writing to a British public, Rallier du Baty emphasized the French interest in “their” marine mammal resources. But elephant seals were more than mere resources, and Rallier du Baty and his crew struggled to reconcile their identification with seals and their violence against them.

Topographic map of the Kerguelen Islands.

Topographic map of the Kerguelen Islands.

Map by Rémi Kaupp. Click here to view source

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

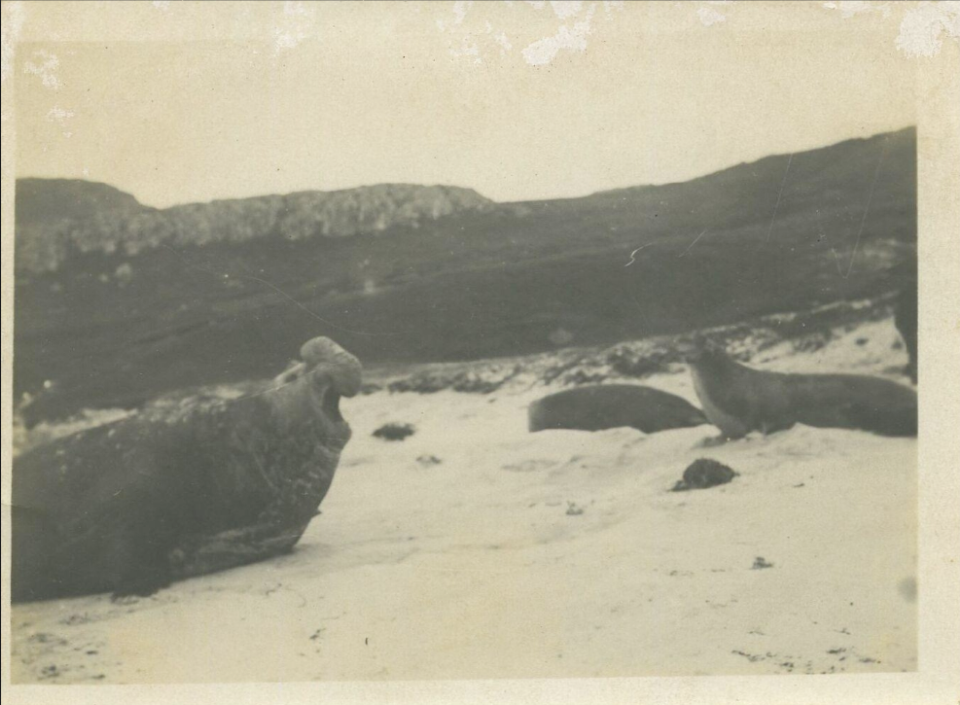

The crew of the J.B. Charcot first encountered elephant seals at the height of the austral summer, when southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) migrate to the Kerguelen Islands en masse to breed, give birth, and molt. At Port Christmas, “some of the families were asleep or scratching themselves cosily with their flippers.” Rallier du Baty even identified “an old bull” who “lay among his wives telling them stories perhaps of the days far back in his life when the man-hunter first came with his death-dealing weapons to massacre his herds.” Drawing on authors like Rudyard Kipling in “The White Seal,” Rallier du Baty ascribed subjectivity to elephant seals throughout his narrative. Elephant seal pups were “mirthful and full of pranks and the sheer joy of life.” Their mothers “watched their little ones” and sang them Kipling’s lullaby: “Splash and grow strong / And you can’t be wrong / Child of the open sea!” And “it was a great and glorious thing” to watch adult elephant seals, “unmoved with dauntless strength and courage,” return to the ocean.

Elephant seals were not just “strangely human” companions to human visitors to the Kerguelen Islands, however. They were also prey. As seal families “lay there lazily, suspecting no danger,” the crew of the J.B. Charcot “came upon them suddenly, armed with clubs and one gun.” Meanwhile, “the old bull I shot through the head.” The knowledge and history Rallier du Baty imagined that the old bull possessed ended with a summary execution.

A male southern elephant seal, mouth open, with two juvenile elephant seals in the background. This photograph was taken by the entrepreneur René Bossière, who helped fund Rallier du Baty’s voyage.

A male southern elephant seal, mouth open, with two juvenile elephant seals in the background. This photograph was taken by the entrepreneur René Bossière, who helped fund Rallier du Baty’s voyage.

Photograph by René Bossière, 1913.

© Archives Pierre Petit - Archipôles, les archives polaires françaises, https://archives-polaires.fr/idurl/1/23543.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

As an observer, Rallier du Baty identified with “mirthful,” “dauntless,” and “cozy” elephant seals. As a hunter, he rejected them. After describing a “sheer massacre” wrought by his crew, Rallier du Baty argued that “one need not sentimentalise over sea-elephants. Their only use to the world is to provide blubber, and on the rocks of the world’s wild places they lead a lazy life, varied only by savage and bloodthirsty fights.” As “lazy,” “bloodthirsty,” and “savage,” elephant seals’ lives lacked redeeming value in a world governed by profit. In the hunt, elephant seals became “so ungainly, so monstrous, so hideous,” with “their huge squat bodies crawling after us,” that they “called to the old brute strength in man by which he became master of the world.” Human violence turned lively, fascinating elephant seals into monsters. While their blubber was a coveted commodity, the lives of elephant seals were abject, disgusting, and meriting extermination.

Seal hunters on a rowboat surrounded by seaweed. Norwegian and South African laborers worked as seal hunters on the Kerguelen Islands, contracting with the French enterpreneurs who leased the archipelago from the French government.

Seal hunters on a rowboat surrounded by seaweed. Norwegian and South African laborers worked as seal hunters on the Kerguelen Islands, contracting with the French enterpreneurs who leased the archipelago from the French government.

Photograph by Etienne Peau, 1923.

© Archives Pierre Petit - Archipôles, les archives polaires françaises, https://archives-polaires.fr/idurl/1/23560.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

It took psychological work to reject human identification with elephant seals, even as it took physical work to turn living beings into industrial oil. Both forms of work transformed the crew of the J.B. Charcot in turn. “We made ourselves an abomination to Nature,” Rallier du Baty wrote, describing the deck swimming in blood and grease and the foul smell that carried for miles on the wind while elephant seal blubber boiled in kettles on the ship. As blubber, grease, and oil worked its way into his clothing, hair, and skin, he became “a living grease spot, contaminating everything I touched.” In the violent rejection of their sympathy for elephant seals, the crew became as “monstrous,” “hideous,” and “savage” as the elephant seals they slaughtered. And the crew’s labor transformed them, too, into a commodity—the 180 casks of high-quality oil they produced “was almost like our life’s blood.”

Southern elephant seals resting on the Kerguelen Islands in 2020.

Southern elephant seals resting on the Kerguelen Islands in 2020.

Photograph by Antoine Lamielle, 2020.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Rallier du Baty was not alone in his troubled relationship with elephant seals. Within twenty years of his visit, the Kerguelen Islands were a key site in the global marine mammal oil industry, where Norwegian, British, and French laborers, equipped with surplus weaponry from World War I, slaughtered tens of thousands of seals for their oil. In 1924, responding to outcry from the growing international conservation movement, the French government decreed that certain areas of the Kerguelen Islands would become a “French Antarctic National Park,” where hunting was forbidden. But as Professor Abel Gruvel, chair of the Commission for the Protection of Colonial Flora and Fauna, would lament over the following years, “We know absolutely nothing about what is happening down there.” But Raymond Rallier du Baty did. His narrative provides us with a vivid glimpse of the messy physical and psychological labor that transformed elephant seals from kindred spirits to monstrous enemies and, in turn, from living beings to a tradeable commodities.

Primary Sources

- Rallier du Baty, Raymond. 15,000 Miles in a Ketch. London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1912.

- Kipling, Rudyard. “The White Seal.” In The Jungle Book. London, 1894; Project Gutenberg, January 16, 2006. https://gutenberg.org/ebooks/236.

How to cite

Sinclair, Katherine. “‘Cozy Families’ or ‘Hideous Brutes’?—Working with Southern Elephant Seals on the French Kerguelen Islands.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2025), no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9921.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2025 Katherine Sinclair

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Arnaud, Patrick M., Jean Beurois, Pierre Couesnon, and Jean-François Le Mouël. Phoquiers de la Désolation: La chasse aux éléphants de mer aux Îles Kerguelen par les navires-usines françaises (1925–1931). Marseille: Éditions Françoise Jambois, 2007.

- Hart, Ian. Austral Enterprises: A History of Shore, Bay-Based, and Pelagic Whaling and Sealing in the Southern Ocean Encompassing The Southern Whaling & Sealing Company, The Kerguelen Whaling & Sealing Company and Their Assorted Enterprises at South Georgia, the Antarctic Peninsula, the South Indian Ocean and South Africa. Herefordshire, UK: Pequena, 2020.

- MacKenzie, John M. The Empire of Nature. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

- Martin-Nielsen, Janet. A Few Acres of Ice: Environment, Sovereignty, and Grandeur in the French Antarctic. Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2023.

- Shukin, Nicole. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

- Sinclair, Katherine. “Frontiers of Sovereignty: An Environmental History of Law, Science, and Profit on the French Kerguelen Islands.” PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2024.

- Soluri, John. "Fur Sealing and Unsettled Sovereignties." In Crossing Empires: Taking U.S. History into Transimperial Terrain. Edited by Kristin L. Hoganson and Jay Sexton. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.