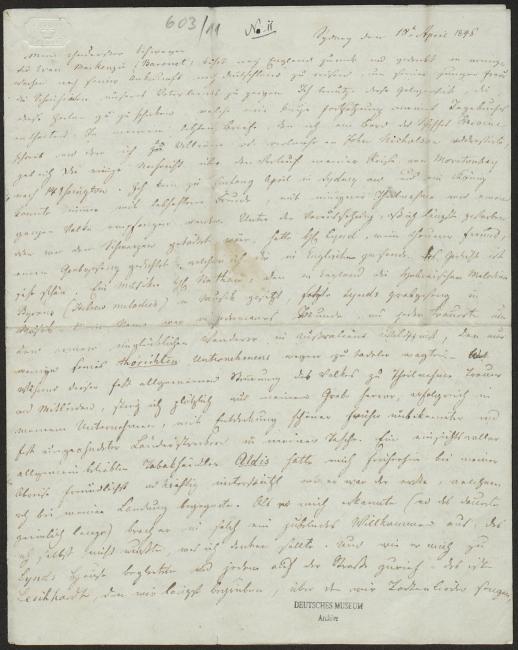

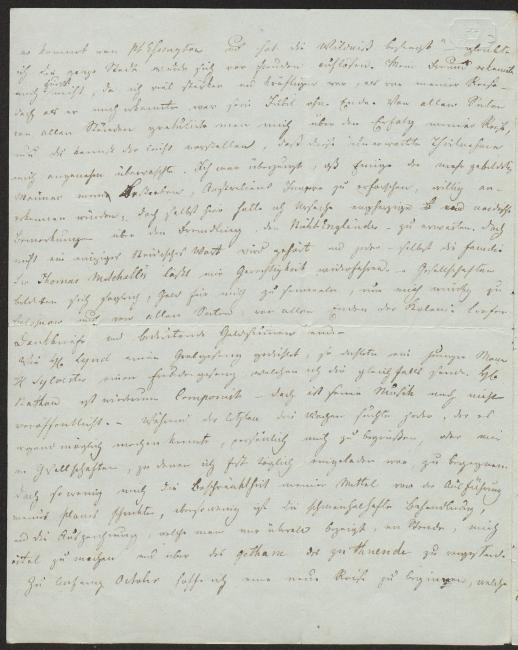

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Sydney (18 April 1846)

Sydney, 18 April 1846

My dearest brother-in-law,

Sir Evan Mackenzie (Baronet) is returning to England and plans on traveling to Germany a few weeks after his arrival, so as to show his young wife the beauties of our fatherland. I am seizing this opportunity to send you these lines, which contain a brief continuation of my journal. In my last letter, which I composed aboard the ship Heroine and which I addressed to William, or rather John Nicholson, I gave you an account of the course of my journey from Moreton Bay to Port Essington. I arrived in Sydney at the beginning of April, and a king could not have been welcomed with more animated joy, more heartfelt interest shown by an entire people. Supposing that I had long since died or been killed by blacks, Mr. Lynd, my dear friend, had composed a dirge, which I am sending you in English. The poem is very nice. A musician, Mr. Nathan, who set Byron’s Hebrew Melodies to music in England, set Lynd’s dirge to music. — My name was on everyone’s lips and everyone grieved the poor, unfortunate traveler through Australia’s wilderness, who only a few dared to criticize for his foolhardy endeavor. — While people shared in this almost universal feeling of concern, grief, and sympathy, I suddenly emerged out of my grave, successful in my endeavor, with discoveries of beautiful, previously unknown and barely imagined stretches of land in my pocket. A kind, universally liked tobacco trader named Aldis had strongly supported me with all kindness earlier, before my departure, and he was the first person I encountered after landing. When he recognized me (which took a long while) he welcomed me with such exultation that I did not know what to make of it. And as he accompanied me to Lynd’s house and shouted to everyone in the street “this is Leichhardt, who we’ve long since buried,

for whom we sang dirges, he comes from Port Essington and has conquered the wilderness” — I thought the entire city would dissolve into joy. My friend at first did not recognize me, since I was much bigger and stronger than I had been before my journey—yet when he recognized me his rejoicing knew no end. I received congratulations on the success of my journey from all sides and all quarters of society, and you can easily imagine that this unexpected interest pleasantly surprised me. I had been certain that some of the more educated men would favorably regard my endeavor to explore Australia’s interior; yet even in these circles I had occasion to anticipate narrow-minded and jealous remarks about the stranger, the non-Englishman. Yet I have not heard a single word of jealousy and even the family of Sir Thomas Mitchell treats me justly. — Societies were formed at once to raise money on my behalf so as to bestow a fitting reward upon me, and letters of thanks and substantial sums of money arrived from all sides, from all corners of the colony. —

Much as Mr. Lynd had composed a dirge, a young man, Mr. Sylvester, composed a hymn of joy, which I am also sending you. Mr. Nathan once again is setting it to music—yet his music has not been published yet. — Over the course of the last three weeks everyone who could manage it sought to pay their personal respects or sought my company at social functions, to which I am invited almost on a daily basis. Yet just as my meager resources failed to deter me from carrying out my plan, the flattering treatment and the accolades that I am everywhere accorded will not cause me to become vain and forget what remains to be done in light of what has been done already.

I hope to embark on a new expedition at the beginning of October, which,

although longer, should nevertheless be more interesting than the last one. I hope to return from Swan River in two years, because I intend to travel up to the tropics, to press toward the north-west coast of Australia at 22°–23° latitude, and to follow it southward to Swan River. At 23° 30’ latitude I crossed and left a river which, although not flowing, contained an ample amount of water. I now wish to follow this river upstream and at its source hope to discover the origins of the tributaries of the Burdekin or the origins of the river system of the Gulf of Carpentaria, which I am hoping to find at about 22°–23° latitude. On the plateau which I postulate for this water system I then want to head westward to the Cambridge Gulf and then to turn southward and to travel to Swan River about 150–200 English miles inland, parallel to the coast. I sent letters to India to obtain camels and will at the very least try to obtain the two camels that are already in the colony.

During my last journey, as well as in my present happy circumstances, and in my dreams of the impending expedition I constantly hear dear mother and father’s words of farewell in my ears: “The Lord will not leave you, my son.” This simple saying not only calms budding fears and fills me with renewed courage, but also serves as a constant reminder to associate the happy success of a dangerous venture with the ministration and protection of a benevolent heavenly Father.

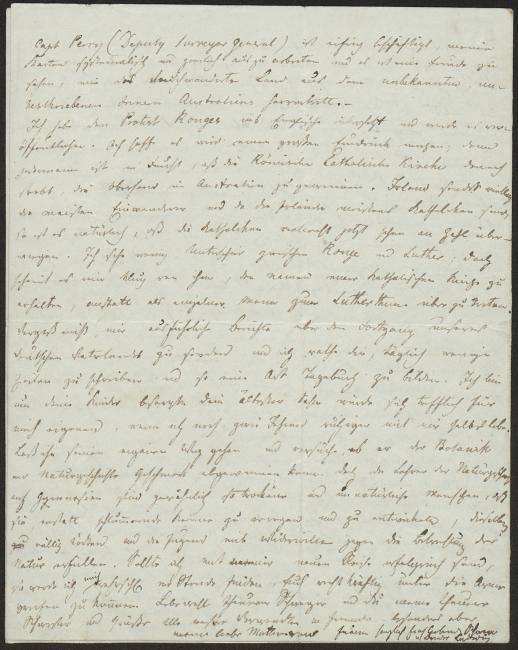

Captain Perry (Deputy Surveyor General) is very busy preparing systematic and elegant renderings of my maps, and it is a joy to observe how the land I wandered through emerges out of Australia’s unknown, blank interior. —

I have translated Ronge’s protest into English and will publish it. I hope it will have a great impact, because everyone fears that the Roman Catholic Church aspires to gain the upper hand in Australia. Ireland probably sends the most immigrants and since the majority of the Irish are Catholic it is only natural that Catholics probably already dominate in numbers. I see little difference between Ronge and Luther; yet I think it is prudent on his part to uphold the Catholic Church in name instead of converting to Lutheranism as an individual. Do not forget to send me detailed reports about the developments in our dear Germany and I recommend that you write a few lines every day so as to keep a sort of journal. I am thinking about your children. Your eldest son would suit me admirably, provided I am more at peace with myself within two years. Let him forge his own path and see whether he has any interest in botany and natural history. Yet teachers of natural history in the secondary schools are usually such stiff and boring people that they completely kill the dormant seeds instead of waking and nurturing them, and they instill in youth distaste for observing nature. Should my new expedition be met with success, I will most likely be in a position to give you a hand financially.

Farewell dearest brother-in-law, and you, my dear sister, and convey my greetings to all of our relatives and friends—but especially to my beloved mother, from your affectionate and loving brother-in-law and brother

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/11.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.