The Mapping of Wilderness—French

Wilderness has no ready translation as a noun in modern French. The general concept is not exactly missing; it is rather left unnamed even when it is mapped.

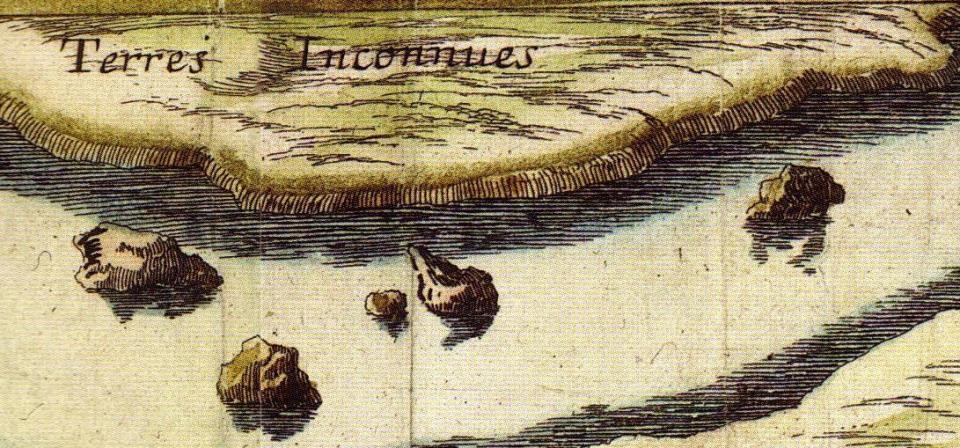

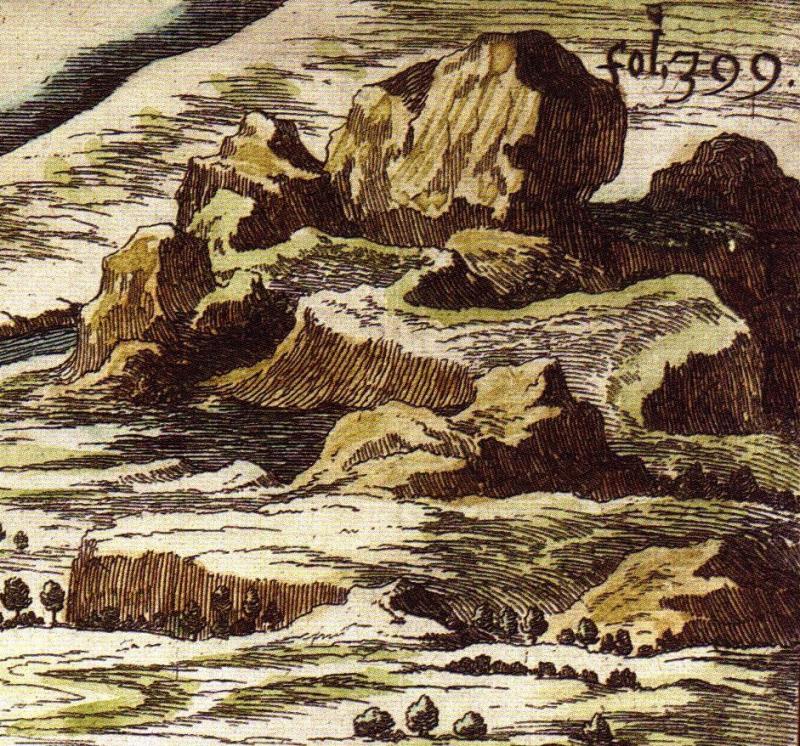

On the allegorical “Carte de Tendre” by Madeleine de Scudéry (1654), wilderness is an isolated island on top of the map. Called Terres Inconnues, it is surrounded by the reefs of Mer Dangereuse. The same map shows another kind of wilderness in its northeastern corner. It is about 12 “Friendship Leagues” long, and consists of treeless plateaus, cliffs, and gorges. From this mountain without a name flows the Estime River, which can be crossed at the city of Tendre-sur-Estime. A smaller wilderness area lies in the West, separating Mer Dangereuse from Mer d’Inimitié.

Detail of the “Carte du Tendre,” 1654.

Detail of the “Carte du Tendre,” 1654.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF)

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Wild could be translated as sauvage (from the Latin silva or forest), and we could suggest for wilderness both la nature and la barbarie. Wilderness is primarily an isolated, dangerous, almost frightening place, a refuge for cruel bandits, moody poets, and misanthropic philosophers. Applied to specific areas, wilderness can mean jungle (forêt vierge) or desert, physically or metaphorically, or land lying fallow. In all cases it means an area empty of inhabitants that terrain, size, and climate have made unsuitable to agriculture. The badlands of the Southern French Alps and the rainforest of Guyana would be in that sense considered wilderness.

Detail of the “Carte du Tendre,” 1654.

Detail of the “Carte du Tendre,” 1654.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

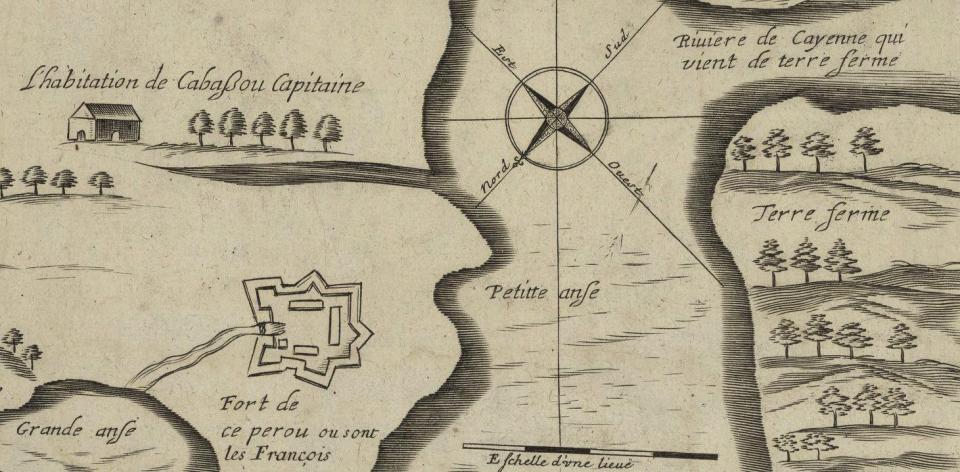

In the “Carte de l’isle Cayenne” by Jacques Lagniet (1665), coste sauvage was another name for the El Dorado kingdom and the land of the Amazons. With its fort and barracks, seigneurial mansions, alignment of trees, and promises of order and wealth, the island of Cayenne stands in contrast with the poorly mapped rainforest of the mainland wilderness. Made a decade earlier, just when the French landed in Cayenne, another map of Guyana was more explicit on the natural bounties of the American mainland: “Terre propre au sucre, au tabac et au cotton; Ici on trouve des pierres semblables aux Rubis; Bois où il y a force perroquets et guenons.” (Land fit for sugar, tobacco, and cotton; Here one finds stones resembling rubies; Woods where parrots and monkeys are many.) Those French explorers and scholars who expected to find attractive the wilderness of the New World braced themselves for disappointment.

Detail of Jacques Lagniet’s “Carte de l’Isle Cayenne,” 1665.

Detail of Jacques Lagniet’s “Carte de l’Isle Cayenne,” 1665.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Despite all its diversity, wilderness is beyond the comfort zone of French civilization. Roads do not lead to wilderness. For French classical geographers like Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, premier géographe du Roi, wilderness should be left blank on the map. In the “Quatrième feuille de la Tartarie chinoise” (1731), the wilderness of the Altai Gobi desert is expressed by the absence of any feature, apart from isolated hills and ranges far in the East of the oasis of Hami.

Detail of JBB d’Anville’s “Quatrième feuille de la Tartarie Chinoise,” 1734.

Detail of JBB d’Anville’s “Quatrième feuille de la Tartarie Chinoise,” 1734.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Cartographic Institute, Paris. “Zones d’attraction du Transsaharien,” 1930.

Cartographic Institute, Paris. “Zones d’attraction du Transsaharien,” 1930.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque nationale de France (BnF).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Conversely, deleting désert or sauvage from the map title is enough to convert wilderness into a territory we can identify with. The map of “Zone d’attraction du Transsaharien” of the Cartographic Institute of Paris (1930) displays the planned railway network that will someday connect Dakar, Abidjan, and Timbuktu to Algiers. The thick Transsaharien line divides the Sahara and makes its vast emptiness irrelevant. Wilderness has been surveyed, mapped, tamed, conquered, and eventually deprived of its name.

What does wilderness mean in your language? Browse “Wilderness Babel” via the map.

Live map showing the location of the languages featured in the virtual exhibition. What does wilderness mean in your language? Browse “Wilderness Babel” via the map.

- Doucey, Bruno ed. Le livre des déserts. Itinéraires scientifiques, littéraires et spirituels. Paris: Robert Laffont, 2006.

- Grandsart, Didier. Paris 1931. Revoir l'exposition coloniale. Paris: FVW Editions, 2010.

- Hofmann, Catherine, ed. Artistes de la carte. De la Renaissance au XXI siècle. Paris: Editions Autrement, 2012.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Tristes tropiques. Paris: Plon, 1955.

- Staszak, Jean-François. Géographies de Gauguin. Paris: Editions Bréal, 2003.

- Tournier, Michel. Vendredi ou les limbes du Pacifique. Paris: Gallimard, 1972.