Defining Wilderness—Japanese

The word “wilderness” is not easily translated or defined in Japanese. 荒野 (kouya) is the most direct translation; it literally means “rough and dry fields (or open space).” People associate it with large deserts and wastelands, even though these do not exist in Japan. As such, this word is very uncommon in the daily speech of most Japanese people.

The term 原生 (gensei), on the other hand, may be used to mean “wilderness,” although its literal translation is “primitive.” For example, the term 原生保護 (gensei-hogo) is sometimes used for “wilderness conservation/areas.” The Japanese Ministry of Environment uses this term and defines these areas as places “that preserve and maintain the original ecosystem and that are free of human influence.”

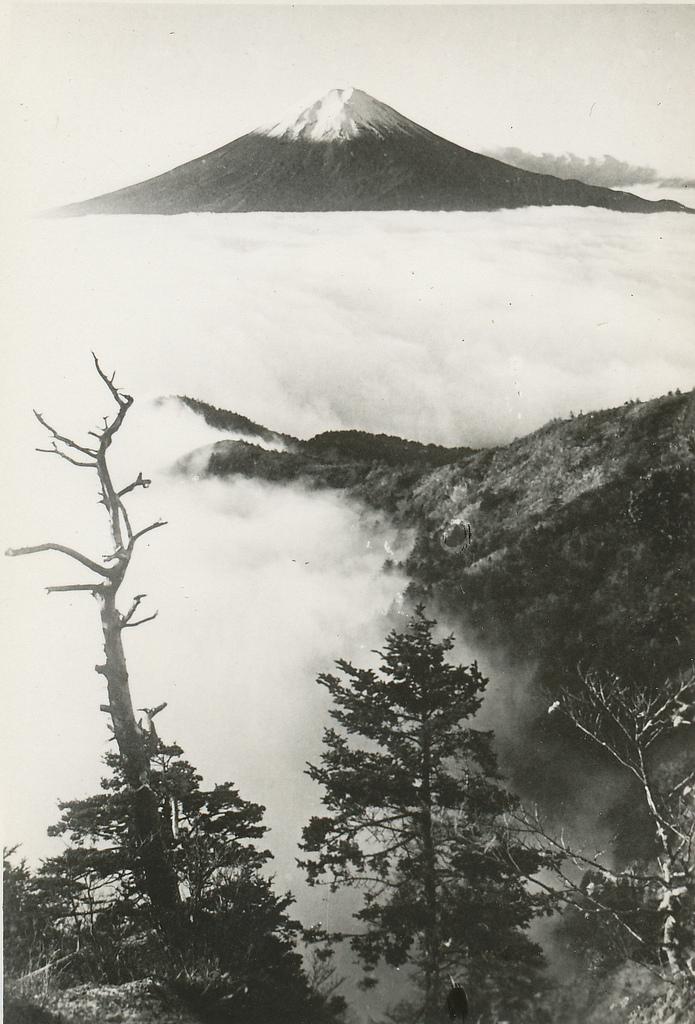

Mount Fuji as seen in the 1950s. This photo blends ideas of wilderness, spirituality, and man conquering nature. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Mount Fuji as seen in the 1950s. This photo blends ideas of wilderness, spirituality, and man conquering nature. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Mt. Fuji above the Fog, 8 selected photographs to benefit the Japan Orphan Aid Society, c. 1950

Courtesy of Joel Abroad. Accessed via Flickr. Click here to view image source.

Series “8 photographs to benefit the Japan Orphan Aid Society, c. 1950.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

荒野 (kouya)

原生 (gensei)

原生保護 (gensei-hogo)

野外 (yagai)

アウトドア (autodoa)

The live site contains audio files of the pronunciation of the Japanese terms kouya,gensei, gensei-hogo, yagai, and autodoa.

Protected wilderness areas with no entry-restricted zones: the head of the Tokachi River in Hokkaido (northern Japan). Photograph by Satoshi Sawada, 2009.

Protected wilderness areas with no entry-restricted zones: the head of the Tokachi River in Hokkaido (northern Japan). Photograph by Satoshi Sawada, 2009.

Accessed via Flickr. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Forest on Yakushima Island in Kagoshima (southern Japan). Photograph by Genta Masuda, 2007.

Forest on Yakushima Island in Kagoshima (southern Japan). Photograph by Genta Masuda, 2007.

Accessed vi Flickr. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

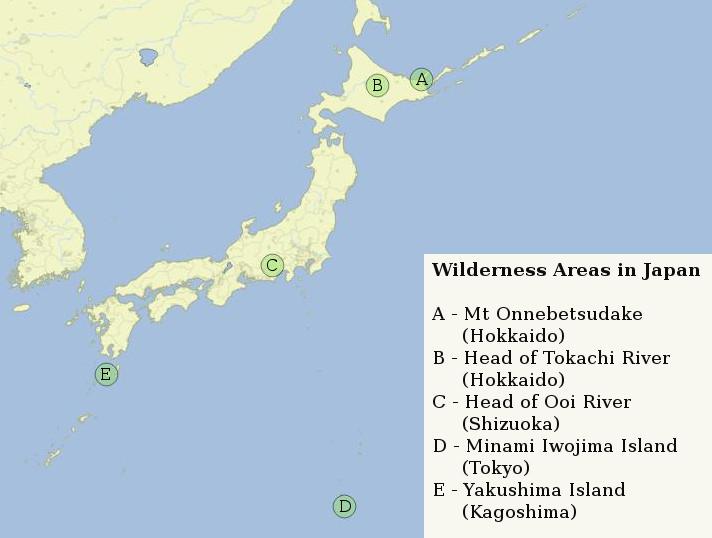

Currently there are only five areas classified as “wilderness areas” in the whole country; they amount to a total of 5,631 ha. Representing only two islands, two river headwaters, and one mountain, these areas cover only a small selection of the different habitat types within the large geographic range of Japan, which spans Hokkaido all the way down to Kagoshima. Other places, such as national parks, fall under the more general term “conservation area.” People may enter theses areas for recreational use.

Map of Official Wilderness Areas in Japan. Vector data courtesy of Natural Earth.

Map of Official Wilderness Areas in Japan. Vector data courtesy of Natural Earth.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Some Japanese companies offering outdoor experiences and first-aid courses refer to wilderness using the term 野外 (yagai), literally “outdoors.” And recently, with more and more English words being adopted into the Japanese language, people simply use a katakana version of the English word outdoors: アウトドア (autodoa). This understanding of wilderness as a place away from people and large towns can be seen in the famous and proudly displayed image of Mount Fuji. It is a place to be awed and respected all at once. Offering both the spiritual meaning associated with mountain tops and a perceived distance from everyday life, Mount Fuji is an interesting example of how ideas are changing over time. In the last decade the number of people climbing Mount Fuji every year has been pushed to the limit, with around 300,000 visitors making it to the top and 6 million more going up to the halfway mark by bus or car. On top of this iconic volcano there is now a growing village with noodle restaurants, souvenir shops, and even a post office.

Today’s ideas of wilderness in Japan seem to vary from a general notion of the outdoors to a more remote wild place with little influence from humans. This stems in part from traditional ideas in the Shinto religion, according to which nature and people’s lives are inexplicably linked. Gods are thought to exist everywhere: in plants and animals, in the wind and the waves, and in the mountains themselves. Shintoists believe in a harmonic balance between themselves and their surroundings. Hayashi (2000) suggests that this understanding of nature has changed with influences from China and America over the past few decades. While people originally believed that nature had the power to heal itself, they are now coming to the new belief that people need to manage nature. Management techniques of conservation and wilderness areas are often based on US models, like the Wilderness Act of 1964. No doubt the Japanese understanding of wilderness will continue to change as international conservation ideas spread and influence management techniques applied to these areas.

What does wilderness mean in your language? Browse “Wilderness Babel” via the map.

Live map showing the location of the languages featured in the virtual exhibition. What does wilderness mean in your language? Browse “Wilderness Babel” via the map.

- Colquhoun, Phil. “Mount Fuji World Heritage Tag: A Pandora’s Box for the Iconic Peak?” Tokyo Weekender, 16 August 2013.

- Hayashi, Aya. “Finding the Voice of Japanese Wilderness.” International Journal of Wilderness 8, no. 2 (2002): 34–37.

- Senda, Minoru. “Japan’s Traditional View of Nature and Interpretation of Landscape.” GeoJournal 26, no. 2 (1992):129–34.

- Yannakos, Alexandra. “You Can’t Translate the Word ‘Wilderness.’” The Leader, Fall 2004.