Why Europe Responded Differently from the United States

[Many believe] that many of the practices condemned by Miss Carson do not go on in this country on anything like the same scale as in the United States of America, of which she was writing. We have nothing like the savage spraying of roadside and railside verges … nor anything like the massive eradication campaigns such as those against the gypsy moth and fire ant she describes. Indeed, the pattern of our agriculture, with its relatively small fields, numerous hedges, and varied crops, does not lend itself to similar scales on anything like the same scale as she describes.

—Viscount Hailsham, British Lord President of the Council and Minister for Science (Parliamentary Debates 1963, 1142–43)

If Silent Spring catalyzed the formation of the American environmental movement, it played no such role in Europe. Why not? After all, fallout from nuclear weapons testing and the thalidomide tragedy worried Europeans as well. Both featured prominently in the debate in the House of Lords, for example, and European debate over radiation echoed arguments across the Atlantic.

Europeans simply didn’t want to believe that Silent Spring applied to them. As Lord Douglas of Barloch noted, they “may say that these things can happen in the United States, but they cannot happen here” (Parliamentary Debates, 1118). The French Commission for Studying the Influence of Treatments on Biocenoses (i.e., ecosystems) declared that “the facts referred to by Miss R. Carson are probably true for the USA,” but that “the belief that European, particularly French, legislation does not protect populations from the dangers of excessive use of insecticides is wrong” (Jas 2007, 3). A reviewer for the Seville newspaper A B C commented that it was good that Spain lagged so far behind the United States, because Spain did not yet have the problem of pesticides and could learn from American mistakes (Andalucia ed., 19 May 1963, 62).

In Denmark, which today like Germany enjoys a very “Green” reputation, the press took note of the American controversy over Silent Spring but concluded that this was mainly an American problem. In Italy and Spain, reaction was similar. Response to Silent Spring resembled a pebble dropped in a pond: a small splash, a few ripples, and it was gone. With few exceptions, public and governments alike remained complacent.

In Eastern Europe, communist countries generally regarded these environmental problems as products of capitalism.

That almost all of Carson’s examples occurred in the United States certainly could give the impression that Americans were exceptionally prone to carelessly overuse of pesticides. Hailsham was correct, too, that European agriculture did not generally have American agriculture’s large farms, extensive monocultures, and consequent need for pesticides. Airplanes did not spray European fields with chemicals, except in East Germany. Europeans regarded American “savage spraying” and “massive eradication campaigns” against insect pests like the gypsy moth and fire ant with considerable skepticism. Moreover, Europeans tended to trust their governments more than Americans do and had confidence in scientists to protect them from harmful environmental chemicals.

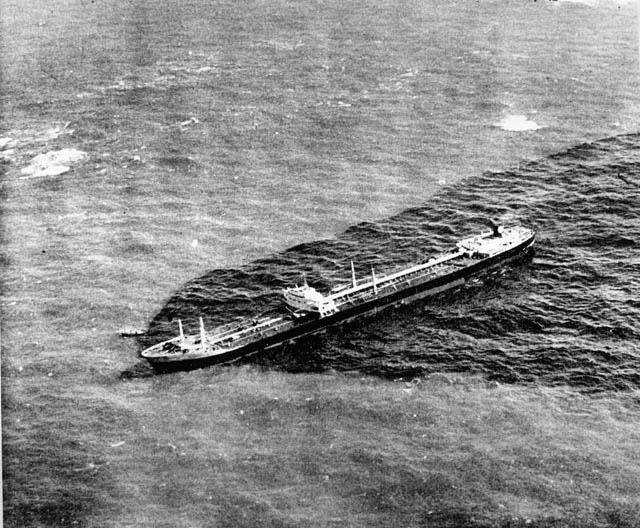

On 18 March, 1967, SS Torrey Canyon caused a serious oil spill outside the coast of England. Unknown photographer.

On 18 March, 1967, SS Torrey Canyon caused a serious oil spill outside the coast of England. Unknown photographer.

© The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, VA. Federal ID Number: 54-054 1801. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This faith that “it can’t happen here” would be shattered as environmental disasters shocked each European country and launched the movements that grew into Green parties. In 1967 the oil tanker Torrey Canyon struck a reef and spilled oil that fouled hundreds of miles of rugged, beautiful, and ecologically fragile coastline in southwestern Britain and northwestern France. Some historians date the beginning of environmental concern in those countries to that event. In Italy, a chemical plant explosion in 1976 released a cloud of the toxic chemical dioxin into the community of Seveso and first raised widespread concern in Italy about chemicals in the environment. Concerns about the dangers of nuclear power stirred up an antinuclear movement across Western Europe. The 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which spread radiation across Europe, horrified all Europeans. The anti-nuclear power movement and the Chernobyl disaster gave tremendous momentum to the speedy rise of Green parties throughout the continent a quarter century after Silent Spring.

The reviewer for the Seville newspaper A B C had point, when he commented that lack of progress had spared Spain the problems of Silent Spring. The same was true of Finland, Ireland, and many other European nations. All of them lagged behind the huge economic growth of the United States after World War II.

The economic lag had political consequences that affected the way Europeans responded to Silent Spring. By 1962 the US had enjoyed a decade and a half of economic growth and prosperity. Americans now felt secure enough to criticize the problems that this growth had caused. The mounting chorus of social criticism included David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950); William H. White, Jr.’s The Organization Man (1956); Vance Packard’s trio The Hidden Persuaders (1957), The Status Seekers (1959), and The Waste Makers (1960); and John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society (1958). Carson, who quoted The Waste Makers, placed Silent Spring in this company by stating that the problem of pesticide overuse “is an accompaniment of our modern way of life” (Carson, 1962, 9).

Since Europe was still emerging from the destruction of the war, Europeans were not yet ready to turn from celebration of the economic miracle to criticism of its environmental, social, and cultural price. In America, environmentalism helped prepare the way for radical cultural, social, and political criticism, while in Europe, the political situation was reversed: environmentalism benefited from political radicalism. Many of leaders and participants in the protests and radical movements of the 1960s later moved into the Green movement: French Greens Brice Lalonde, Serge Moscovici, and Antoine Waechter; French and German Green Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who long was banned from France for his revolutionary activity in 1968; and German Greens Petra Kelly and Joschka Fischer.