Silent Spring in Literature and the Arts

I want to remember Rachel Carson’s spirit. I want it to be both fierce and compassionate at once. I want to carry a sense of indignation inside to shatter the complacency that has seeped into our society. Call it a sacred rage, a rage that is grounded in the knowledge that all life is intertwined. I want to know the grace of wild things that sustains hope.

—Terry Tempest Williams, “The Moral Courage of Rachel Carson”

Rachel Carson happily acknowledged her debt to her literary heroes, the nature writers Henry Beston and Henry Williamson especially, as well as Henry David Thoreau, Richard Jeffries, and H. M. Tomlinson. How appropriate, then, that in some sense every nature writer since Carson, from poets to playwrights, writes in the lengthened shadow of Silent Spring. Quite a number, in fact, allude to her and her book directly, either taking explicit inspiration from Carson and her work or responding to them.

Nature writers who explicitly speak of Carson mention both her profound impact on the modern environmental movement as well as her influence on them personally. Seminal nature writer Scott Russell Sanders lists Carson alongside figures such as Aldo Leopold, John Muir, and Henry David Thoreau (Sanders 2009, 57 and 81). Prolific poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming cites Carson’s Silent Spring as one of the books that have most influenced her. And Rebecca Solnit, whose work often centers on landscape and ecology, credits Silent Spring with leading to “the far greater environmental literacy of the public, the necessary precursor to any broad environmental movement” (Solnit 2007, 300). Environmental philosopher and nature writer Kathleen Dean Moore brings together both reactions in her work. In “The Truth of the Barnacles: Rachel Carson and the Moral Significance of Wonder” Moore links the “sense of wonder” evoked by Carson to environmental ethics. In Wild Comfort: The Solace of Nature, Moore’s collection of introspective essays, Carson’s writings often serve as the springboard for contemplation. She ruminates on Carson’s observations of our interconnectedness with nature while considering her own place in the world around her.

Three literary events pay tribute to Carson and hope to extend her influence. Nature and Environmental Writers - College and University Educators, Inc., (NEW-CUE) sponsors a biennial Environmental Writers’ Conference in honor of Carson that uses nature writing to inspire wonder at the natural world among students and the reading public. Such distinguished literary scholars as Lawrence Buell and Leo Marx have addressed the conferences and award-winning authors Terry Tempest Williams, Mary Oliver, Alison Hawthorne Deming, and Barbara Kingsolver have participated in the lecture series.

Florida Gulf Coast University hosts the Rachel Carson Distinguished Lecture Series, which since 2004 has brought a series of authors and thinkers who have addressed ethical and literary issues regarding the human relation to the earth.

In a more popular vein, since 2007 the EPA, Generations United, the Rachel Carson Council, and the Dance Exchange have annually sponsored “The Sense of Wonder: Rachel Carson Intergenerational Poetry, Essay, Photo and Dance Contest.” The public selects winners in each category.

Poem by Anthony Walton (2011).

Poem by Anthony Walton (2011).

2011 Anthony Walton

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Carson and Silent Spring have inspired a number of poetic responses. The editors of the 2004 collection Wild Reckoning: An Anthology Provoked by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring put together a poetic celebration of the “sense of unity of living things” (Burnside and Riordan 2004, 20), which to them epitomizes Carson’s enduring influence. The poems range throughout literary history, but the editors also commissioned seventeen of the poems especially for the project, asking each poet to work with a scientist to produce a dialog that would result in a poem. Although most of the poems do not mention Carson directly, the idea of putting poets together with scientists comes directly from Carson’s successful blend of science and literature. “The Gift of the Bear,” on the other hand, by Robert Wrigley, six-time winner of the Pushcart Prize, is a direct response to Silent Spring that engages in poetic conversation with Carson’s work.

Other poets pay direct tribute. In 2011, Danielle Devereaux published a cycle of five admiring poems about Carson in the Canadian poetry magazine Arc. African-American poet Anthony Walton meditates on how civilization intrudes on wild places in his 2008 poem “In the Rachel Carson Wildlife Refuge, Thinking of Rachel Carson.” Award-winning Chilean poet Marjorie Agosin’s “Rachel Carson” makes Carson a part of the natural world she sought to save.

Bullfrog Films presents…A Sense of Wonder from Bullfrog Films on Vimeo.

External Link: Bullfrog Films presents…A Sense of Wonder (http://www.pbs.org/asenseofwonder/) from Bullfrog Films on Vimeo (http://vimeo.com/337273726).

In theater, award-winning actress Kaiulani Lee has performed her one-woman play A Sense of Wonder since the 1990s. Focusing on the two-year period between the publication of Silent Spring and Carson’s death, Lee’s play tells Carson’s “courageous” personal story (Lee, Bill Moyers Journal) in the two years after publication of Silent Spring, when she faced celebrity, attacks on her and her work, breast cancer, and responsibility for her orphaned nephew. In its 2007 episode about Carson, Bill Moyers Journal featured extensive selections from the play interspersed with an interview with Lee.

Carson’s life and work have inspired visual art. British sculptor Una Hanbury met her at an Audubon Society dinner shortly before Carson’s death and came away very impressed. She created a portrait in bronze, which today is owned by the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution.

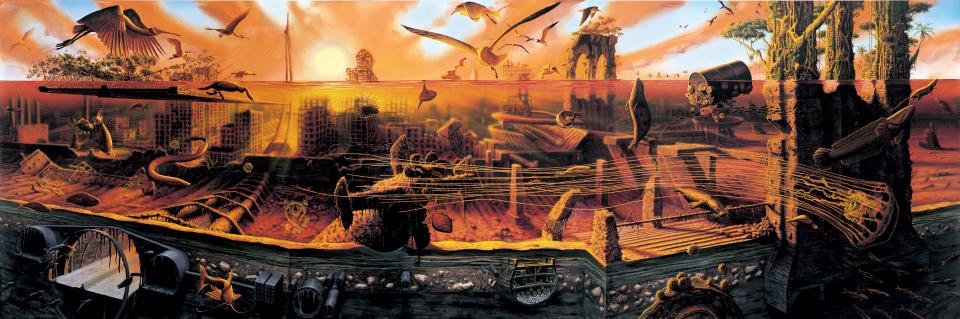

One of the paintings in the exhibit “A Fable for Tomorrow,” Alexis Rockman’s powerful Manifest Destiny depicts the Brooklyn waterfront after global warming has raised sea levels.

One of the paintings in the exhibit “A Fable for Tomorrow,” Alexis Rockman’s powerful Manifest Destiny depicts the Brooklyn waterfront after global warming has raised sea levels.

Manifest Destiny oil on wood, 96 x 288 in.

All rights reserved © 2004

Courtesy of artist Alexis Rockman

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

One of the first contemporary artists to focus his art on environmental issues, Alexis Rockman has described his role as “artist-advocate” (Lovejoy in Marsh 2010, 151). In 2010, the Smithsonian Institution mounted a retrospective of his career and called it “A Fable for Tomorrow,” in explicit reference to the title of the first chapter of Silent Spring. Much like Carson, but in a visual medium, Rockman has used his art to publicize the harmful environmental and ecological consequences of a society unable to control itself.

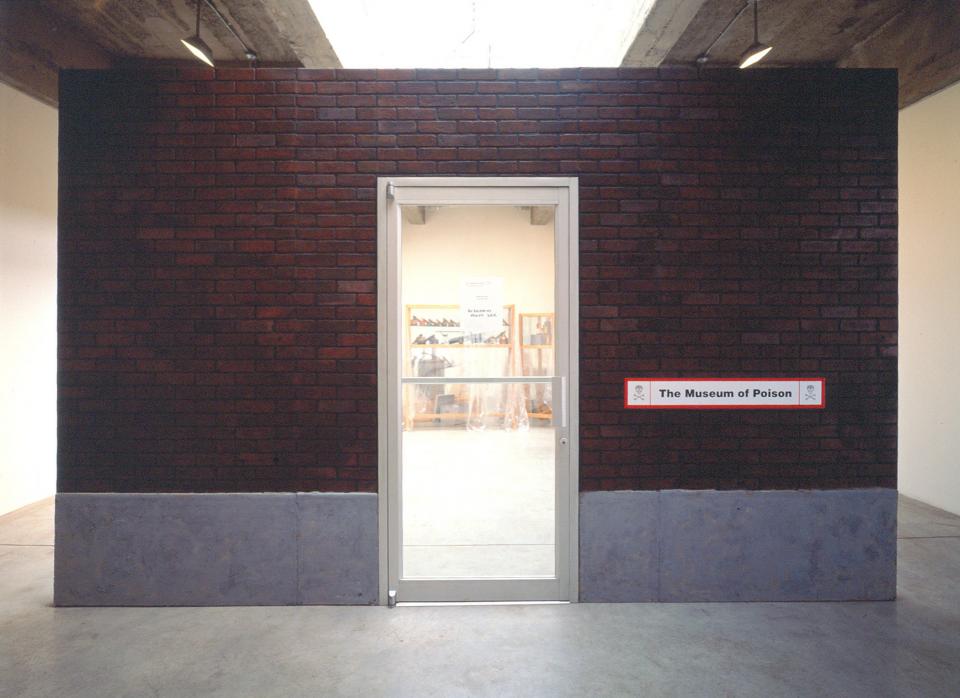

Exterior of Mark Dion’s “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000.

Exterior of Mark Dion’s “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000.

Mark Dion. “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000.

Wood and glass display cabinets, wooden pedestals, pesticide sprayer, pesticide containers, mounted photographs, plastic. Dimensions variable.

Courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Photography: Oren Slor

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Some of the “exhibits” in Mark Dion’s “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000.

Some of the “exhibits” in Mark Dion’s “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000.

Mark Dion. “The Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” 2000. (detail)

Wood and glass display cabinets, wooden pedestals, pesticide sprayer, pesticide containers, mounted photographs, plastic. Dimensions variable.

Courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Photography: Oren Slor

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Rockman is one of a group of artists about the same age who deal with representations of nature. The most prominent of them is Mark Dion. Several of his installations refer directly to Rachel Carson but the most powerful of them was his 2000 “Museum of Poison (Biocide Hall),” exhibited in 2000 at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York City, which Dion called “in some way a portrait of Rachel Carson” (Richards 2004, 244). In a grim parody of a museum, it displayed actual sprayers and canisters of pesticides (or, as Carson suggested they be called, “biocides”), all of which are now banned.