Industrial and Agricultural Interests Fight Back

If man were to follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.

—Robert H. White-Stevens, interview, CBS Reports, 3 April 1963.

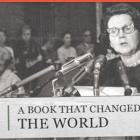

Agriculture and industry did not passively sit by. When they got word of the forthcoming publication of Silent Spring, leaders of the chemical industry launched a counterattack on this threat to its commercial interests. Velsicol Corporation, a manufacturer of chlordane, sent a letter to Houghton Mifflin threatening a libel suit if it published the book. The National Agricultural Chemical Association (NACA) funded a public relations campaign with $25,000, a substantial sum in 1962. NACA took out advertisements, sent letters to the editor, published pamphlets and put out a newspaper insert, all touting the safety and necessity of agricultural chemicals. Carson had friends in the agricultural chemical industry, in agricultural schools, and in government, many of whom had given her information that their bosses were not eager to make public. Scientists and researchers however believed their discoveries benefited farmers and helped feed a growing world.

The banning of DDT portrayed as a threat to people in malaria-ridden countries. Illustration by Chip Bok.

The banning of DDT portrayed as a threat to people in malaria-ridden countries. Illustration by Chip Bok.

Used by permission of Chip Bok and Creators Syndicate, Inc.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Silent Spring placed their work in the sinister context of profit-driven corporations and complicit government and educational institutions. They reacted with hostility to both author and book.

The cover of the magazine Farm Chemicals for October 1963 featured a cartoon in which figures representing three industry spokesmen who testified before Congress forcefully make their case to Uncle Sam, one pounding the table with his fist, another pointing his finger in accusation, and the third gesturing thumbs down. Behind them, a witch on her broomstick flies by. (The publisher of Farm Chemicals, Meister Media International, refused permission to reproduce the cover here.)

Pesticide advocates claimed that without chemicals, agriculture would collapse. In 1963 Monsanto published “The Desolate Year,” a parody of “A Fable for Tomorrow,” Silent Spring’s opening chapter, which described a starving world without chemical pest control. The Montrose Chemical Company, the principal American manufacturer of DDT, publicized 1970 Nobel laureate Norman E. Borlaug’s prediction that without DDT and pesticides, modern agriculture would fail and mass starvation would ensue. Borlaug added diatribes against the National Audubon Society and the Environmental Defense Fund for their opposition to DDT.

NACA and agricultural-chemical manufacturers embarked on a long campaign of misinformation to discredit Silent Spring and the anti-DDT movement. Two chemists at the American Cyanamid Company, Thomas H. Jukes, later professor of medical physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and Robert H. White-Stevens, later professor in the Bureau of Conservation and Environmental Science at Rutgers University, led attacks on Carson, particularly for her criticisms of DDT. Jukes and White-Stevens seized upon the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, held annually since 1900 and published in American Birds, to assert that bird populations had actually increased since the introduction of DDT and chemical pesticides. “Thus robins,” claimed White-Stevens, “over which Miss Carson despairingly cries requiem as they approach extinction, show an increase of nearly 1200% over the past two decades” (White-Stevens 1963, cited in Clement 1972, 446). Widely picked up by agricultural newsletters and newspaper columns, the Bird Count argument was not published in a scientific journal until 1964, when scientists quickly refuted it.

In 1971, Jukes published “D.D.T., Human Health, and the Environment” in Environmental Affairs, charging that banning DDT would create a global prejudice against the chemical that would cause the collapse of the antimalarial campaign and cost human lives. The World Health Organization had insisted for years that DDT was the only cost-effective means to control malaria-carrying mosquitoes. However, already by the early 1970s mosquitoes were everywhere acquiring resistance to DDT due to its overuse in agriculture. WHO reluctantly stopped using DDT against malaria, but not because of Silent Spring.

Nevertheless, American conservatives and libertarians have quite successfully circulated the argument that Carson had provoked a ban on DDT that caused the deaths of millions. A character in Michael Crichton’s 2004 novel State of Fear stated the banning of DDT killed more people than Hitler did, a claim that has spread across the Internet. Articles in such conservative publications as Forbes, Capitalism Magazine, The Washington Times, National Review, and Reason attacked Carson. The libertarian advocacy group Competitive Enterprise Institute created the website RachelWasWrong.org.

The accusation that Silent Spring indirectly killed millions of Africans flooded the Internet in 2007, the centennial of Carson’s birth. The libertarian think tanks American Enterprise Institute and the Cato Institute praised DDT and attacked Carson for maligning an extremely useful and innocuous chemical. The success of this campaign can be measured in the brief spate of articles in the mainstream American media that picked up the charge. The Cato Institute followed up during the 50th anniversary of Silent Spring with publication of a book designed to undermine its argument by Roger E. Meiners, Pierre Desrochers, and Andrew P Morriss, Silent Spring at 50: The False Crises of Rachel Carson.

That these assertions are easily disproved is beside the point. The purpose of the campaign was not to rehabilitate DDT, which actually is only banned in the US. The goal was to undermine confidence in government regulation in general by convincing people that regulation of DDT was disastrous. As Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway have shown in their book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, corporations have used methods developed to counter the science of smoking and health to spread doubt about science and regulation in connection with DDT, acid rain, ozone depletion, and global warming.