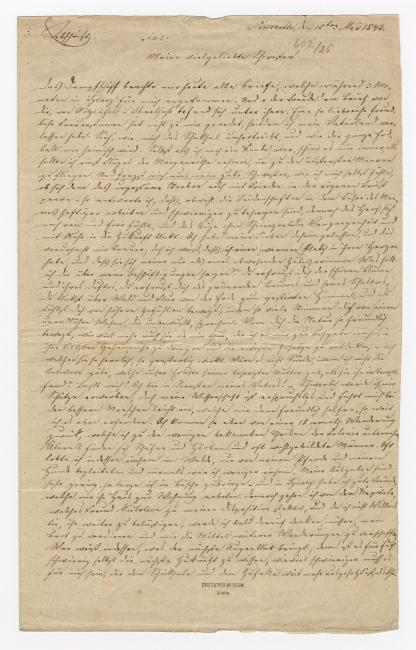

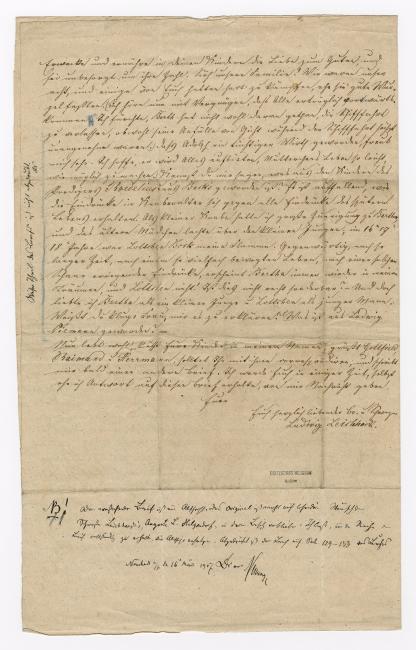

Letter to his sister Auguste L. Hilgenfeld, Newcastle (15 May 1844)

Newcastle, 15 May 1843 [sic, for 1844]

My beloved sister,

Today the steamer brought me all the letters that had arrived for me in Sydney during the last 3 months. Oh, what a delight! A letter from you, from Hilgenfeld, and Schmalfuß were among them. I have not heard such a dear woman’s voice since I left my fatherland. See how far my fate has sent me, and how I am becoming at home in the entire world. Even as a boy, it seemed to me that I might borrow the wings of the dawn in order to fly to the farthest seas. And you ask me, my dear sister, how I feel, whether peace also accompanies the tumultuous striving in my breast—my answer is that, although the passions in a man’s bosom act more fiercely upon him and are more difficult to master, his heart can still remain pure and free, and his eye can contemplate the past without pain and look calmly towards the future. I have left those dear to me at home, and this causes me sorrow; but I know that I have a warm place in their hearts, and that they think of me as a blessing which is absent. What should I tell you about my activities? You take delight in lovely flowers and their scents, you rejoice in the greening tree and the shade it casts, you look out beyond the earth and forest to the starry heavens, and you are moved deeply by so many voices that speak to you of an eternal being hidden from you. If Nature moves you to such affection, just think how it must move me as I make it my task to uncover her deepest secrets and reveal the laws which make her so majestic, so glorious. Would it not be a sin, if I were not to give the answer which our Savior gave to his worried mother when she found him in the temple: “Let me be. Do you not wish that I should serve my Father?” — I am not likely to gain any great amount of riches, but my science does not require much, and it brings me into contact with the best circles, where I receive the most friendly assistance with whatever I might require. I have just returned from an 18-month journey to the lesser-known parts of the colony. Everywhere one meets shepherds and herdsmen, and frequently well-educated men. However, I often lived alone in the woods, in the company of only my horse and my dog—and yet I have never been less lonely. My expenses are very little so long as I am living in the bush—and in Sydney I have good friends who allow me to reside in their houses. Even so, I am living on the funds that my friend Nicholson has placed at my disposal, and since I do not wish to impose upon him any further, I will soon have to think about how to earn my bread myself and obtain the money necessary for additional journeys. Who knows what the next moment will bring; if you two have difficulty foreseeing the immediate future, how much harder it is for me, as I am so much more at the mercy of fate and chance than you.

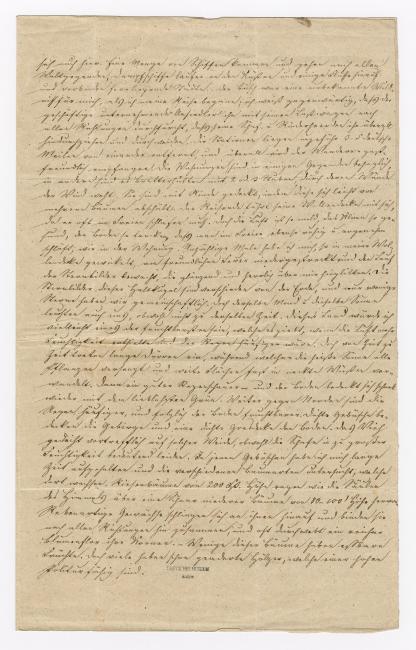

My thanks to Hilgenfeld for his brotherly suggestion; I am delighted that he thinks so highly of me, and I promise to write as long as the postage is not too expensive for you. Know that your faraway brother is close to you in his thoughts, that he is in your presence through his letters, while a neighbor, as long as he remains silent, might just as well be living in the wilds of Australia! Do not forget that, were I to return home, I would be in danger of facing a great deal of unpleasantness from the government. I am not willing to let myself be treated as a deserter—and yet precisely this is likely to be the case. The government has acted in a most foolish manner. Rather than taking advantage of what its native son can offer from abroad, enriching its museums and collections and gathering knowledge about far-off lands, it cast me off, like some wretched miser, when I asked to be freed from my military duty. This is a very sore point for me, and I am ashamed when I must admit here abroad how my womanish government has treated me. In London I was refused a Prussian travel pass to Paris; I was forced to accept a pass from the French consul which listed me as an Englishman. In Paris I attempted to get in contact with the government again. I went to the ambassador and requested a pass to Italy: instead all they wanted to give me was one to Prussia! What could I do? Should I have given up my connection to my brotherly friend and patron Nicholson, which promised me Switzerland, Italy, England, and the far reaches of the world—merely in order to comply with the senseless demand that I serve for a year in Berlin? I wrote to the government, explained my reasons and prospects, and what was the response? “It is impossible for the government to extend your leave beyond 1840.” Nicholson could not suppress a “Goddamn it,” and I hoped that such a sensible government, which in all likelihood has any number of travelers abroad, would come to regret having forced me to become a deserter. Had I been the son of a rich family, they would probably have accommodated this rare opportunity offered to one of the fatherland’s own naturalists. But since I was just the child of a poor farmer, without anyone to advocate for me, the government in its wisdom decided that it could not dispense with a year of military service in order to benefit from a traveler in New Holland. Oh the shame, the shame, the shame! Forgive me for dwelling on the subject for so long; I am angry again whenever I think about it. — Thus I was obliged to seek out scientific connections elsewhere, and [instead] of sending my collections to Berlin, they are now going to England and Paris. You will have learned from my letters to Schmalfuss that this country, although young, is already dotted with numerous towns which are gradually developing. The pleasures of life that Europe has to offer are also available here.

Many ships arrive and depart for all corners of the world, steamers travel along the coasts and several of the rivers and connect distant towns with each other. — To me, the bush seemed to be an uncharted wilderness when I began my journey; now I know that the busy, enterprising settlers are making tracks with their wagons in all directions, that herds of sheep and cattle cross through and pasture in it. The stations are about 3–5 German miles apart, and travelers are received with much hospitality everywhere. In some areas the dwellings are quite cozy, while in others they are mere huts made of boards with 2 or 3 rooms with the wind blowing through the cracks in the walls. They are roofed with bark, which can be stripped easily from a number of tree species. A traveler carries his own woolen blanket with him, for often he must sleep outdoors. But the air is so mild, the climate so healthy, and the ground so dry, that one sleeps just as peacefully and comfortably outside as one does under shelter. On countless occasions I have stretched out beside a pleasant fire, wrapped in my woolen blanket, and watched the movement of the stars as they passed shining and splendid above me. The constellations in this hemisphere are not the same as in [yours], and we share only a very few stars. But the same moon and the same sun shine upon us all, although not at the same time. This land might be one of the most fertile in the world, if the air were more humid and the rain more frequent. But from time to time there are long droughts, during which the sun sears all plant life and nearly turns broad swaths of land into deserts. And then comes a rainstorm—and the earth is quickly covered again with the most lovely green. Further to the north rain is more frequent, and the earth thus is more fertile. The mountains are covered with thick bushes and the ground is thick with grass. Livestock thrives most wonderfully on such pastures, although the sheep suffer notably when there is too much moisture. In these bushes I spent a substantial period of time investigating the various types of trees which grow there. Giant trees 200 feet tall loom like the pillars of heaven above a flock of shorter trees of 80–100’ in height. Vine-like plants wrap around them and bind them together in all directions, and frequently their crowns are woven with a rich festoon of blossoms. — Few of these trees have edible fruits. But many have beautifully grained wood that can be polished to a high gleam.

Awaken and nourish in your children a love for what is good, and do not worry about how many they are. Look at our family! There were eight of us, and some among you faced a difficult struggle before you could set down roots. I fear that Barth made a poor decision when he gave up seafaring, even though his attacks of gout during the sea journeys were very unpleasant. I am delighted to hear that Adolph has become a capable farmer. I hope that he will make the utmost effort to make dear mother’s life as easy as possible. Can you tell me what has become of the children of Pastor Roedelius, and of the Bocks? It is remarkable how impressions from one’s boyhood remain in spite of all that might come after. As a young boy I was greatly devoted to Bertha, and the older girl laughed at the small boy; at 16, 17, and 18 Lottchen Bock was my great flame. At present, after so long, and after a life stirred in so many ways, after so many inspiring impressions, Bertha still appears to me again and again in my dreams, and Lottchen does not! Is this not quite strange? — And yet I loved Bertha as a young boy and Lottchen as a young man. You are a wise woman, can you explain this to me? What has become of Ludwig Riemann? —

Now adieu, give your children a kiss in my name, greet Gottfried, Raimund, Herrmann, if you should happen to correspond with them, and write to me soon. I will give you news in a short while, even before I receive a response to this letter.

Most affectionately,

Your brother and brother-in-law

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 602/25.

English translation by Brenda Black.