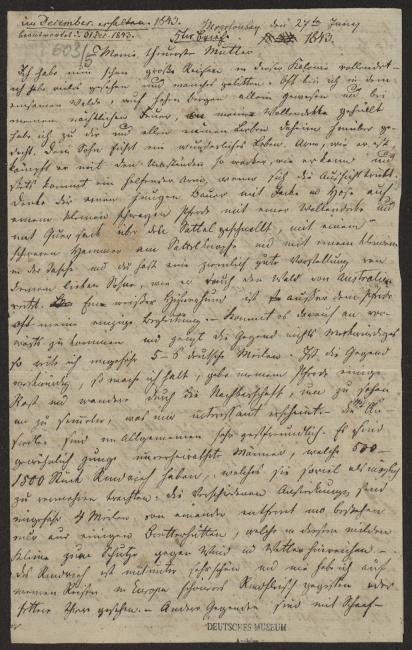

Letter to his mother, Charlotte Sophie Leichhardt, Moreton Bay (27 June 1843)

Moreton Bay, 27 June 1843

My dearest mother,

I have already completed long journeys in these colonies—I have seen much and endured many trials. Alone in isolated forests or high mountains, I have often wrapped myself in my woolen blanket by my nightly fire and directed my thoughts to you and to all my loved ones at home. Your son is living a most remarkable life. Poor as he is, he struggles with the circumstances as valiantly as he is able, and again and again a helping hand comes when prospects seem most dark. Think of a young peasant in jacket and pants on a small black horse, a woolen blanket and satchel strapped across his saddle, a heavy hammer on the saddle horn and a smaller one in his pocket, and you will have fairly accurate vision of your dear son as he rides across the forest of Australia. Besides my horse, a white pointer is often my only companion. — When my goal is to make progress forwards and the landscape does not have anything remarkable to offer, I ride for 5–6 German miles. If the region is notable, I pause, give my horse a rest, and wander about the area in order to look about and collect whatever seems interesting to me. The settlers are generally very hospitable. They are typically young, unmarried men who own 500–1500 head of cattle, which they aim to increase as much as possible. The individual settlements are about 4 miles from each other and consist of several huts made of planks, which offer sufficient protection from wind and weather in this mild climate. — Some of the cattle are very lovely specimens, and I have never eaten such good beef or seen such fat beasts during my travels through Europe. — Other regions are covered with flocks

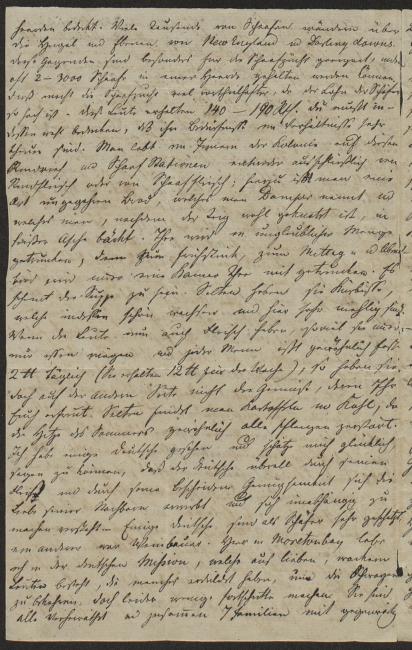

of sheep. Many thousands of sheep wander over the hills and plains of New England and the Darling Downs. These regions are particularly suitable for raising sheep, and often 2–3000 sheep may be kept in a single herd. This makes sheep farming much more profitable, as a shepherd’s wages are so high. They receive 140–190 Rtl. However, you must take into account that their needs are comparatively expensive. In the inner regions of the colony on these cattle or sheep stations, they live entirely off of beef or sheep; in addition they eat a kind of unleavened bread, which is called damper, and which, after the dough has been well kneaded, is baked in fresh ashes. Tee is consumed in unbelievable quantities, for a pitcher of tea is drunk with breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It seems to serve as the soup. On rare occasions they have pumpkins, which grow quite well and are very mealy here. Although the people have as much meat as they can eat—and each man eats nearly 2 lb a day, as a rule (they receive 12 lb per week)—on the other hand they do not have the vegetables which you take pleasure in. Potatoes and cabbage are quite rare, for the heat of the summer typically destroys all the plants. I have met a number of Germans and I am pleased to say that the German wins the affection of his neighbors everywhere because he works hard and is content with modest means, and because he is self-sufficient. — Several of the Germans are highly regarded as shepherds, and another was a wine-grower. Here in Moreton Bay I am living at the German Mission, which consists of good, upright people who have endured much in their attempts to convert the blacks, but have sadly made little progress. They are all married and together number 7 families at present with

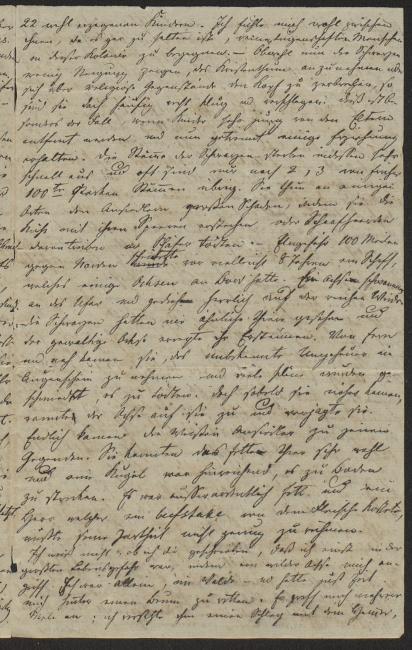

22 well-raised children. I feel at ease among them, for it is far too seldom that one meets such virtuous people in this colony. — Although the blacks show little inclination to become Christian or to concern themselves with religious matters, they are often quite intelligent and shrewd. This is particularly the case when the children have been taken from their parents at a young age and have received a separate education. The black clans are dying out quite quickly at present and often there are only 2 or 3 individuals left in a clan that once numbered more than 100. In some areas they cause great damages for the settlers by killing cattle with their spears or driving away flocks of sheep and killing the shepherds. — About 100 miles to the north a ship with a number of oxen on board was wrecked about 8 years ago. One bullock swam to the shore and thrived wonderfully on the rich pasture. The blacks had never seen such animals and the mighty bullock filled them with wonder. They came from near and far to catch a sight of the unknown monster and there were many plans made for killing it. But as soon as they approached the bullock charged and drove them away. At last the white settlers reached these regions. They were quite familiar with this fat beast, and one bullet sufficed to slay it. It was extremely fat, and one gentleman who had tasted of its meat could not stop praising its tenderness.

I don’t know if I have written to you about how I was once in great danger when a wild bullock attacked me. I was alone in the woods—and just barely managed to save myself behind a tree. He attacked me multiple times; I gave him a blow with my hammer,

this seemed to cool his anger, and I dashed away, ducking behind one tree after another. — During this episode I lost my good hammer, which had accompanied my through France, Switzerland, and Italy—although of course this was greatly preferable to losing my life.

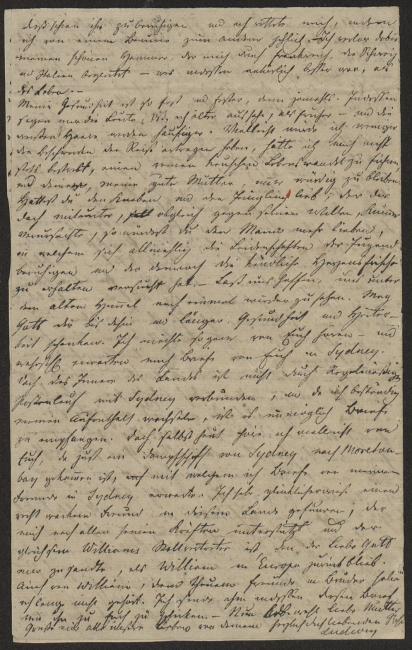

My health is sound, sounder than ever. But people have started to tell me that I look older than before—and the white hairs are becoming more abundant. Perhaps I would have had more difficulty enduring the hardships of travel if I had not always attempted to live a pure and abstinent life and to always remain worthy of the love of my dear mother. If you loved the boy and the youth, who, after all, sometimes caused you sorrow in spite of himself, you would love the man even more, in whom the passions of youth are gradually becoming calmer, even while he strives to preserve the joyful heart of a child. — Let us hope that we will see each other once more beneath the sky of the old world. Until then may God continue to grant you health and happiness. I would so like to hear from you—and probably letters from you are already waiting in Sydney. But the inland regions are not connected to Sydney by a regular postal route, and since I am constantly changing my place of residence, it is impossible to receive letters. Yet I might hear from you today even, for a steamer from Sydney has just arrived at Moreton Bay, which I expect to have letters from my friends in Sydney. I have the good fortune to have found a staunch friend in this country who supports me in any way he can; he might be William’s deputy, sent by the dear Lord to me when William remained behind in Europe. From William, my dear friend and brother, I have not heard anything for some time. Even so, I am sending him this letter to pass on to you.

Now adieu, dear mother. Give my greetings to all, from your dearly loving son.

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/5.

English translation by Brenda Black.