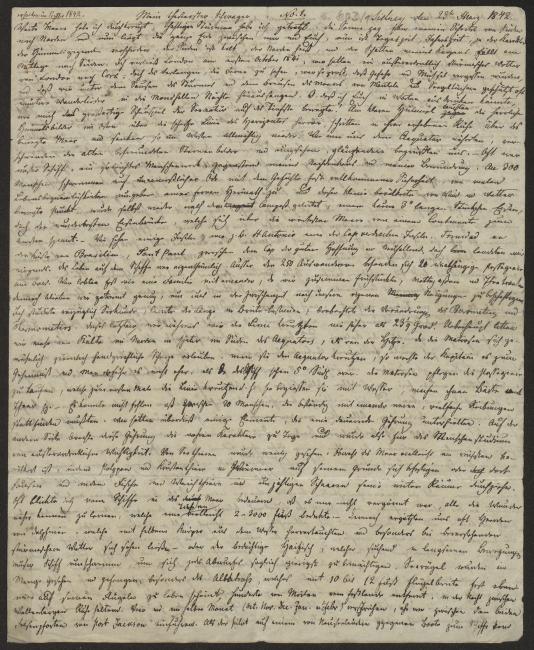

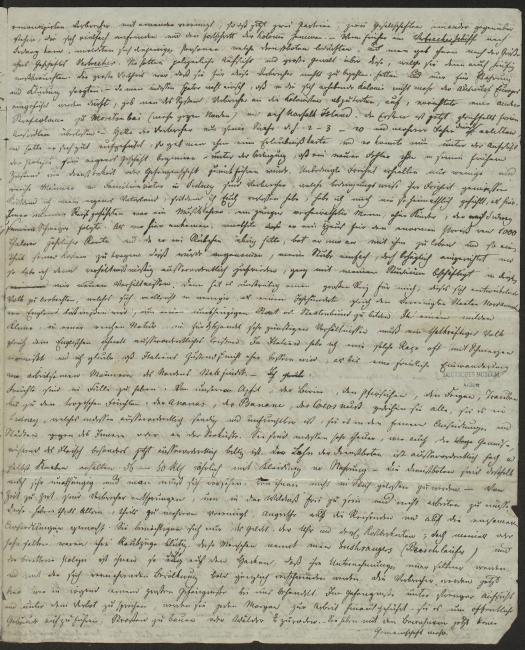

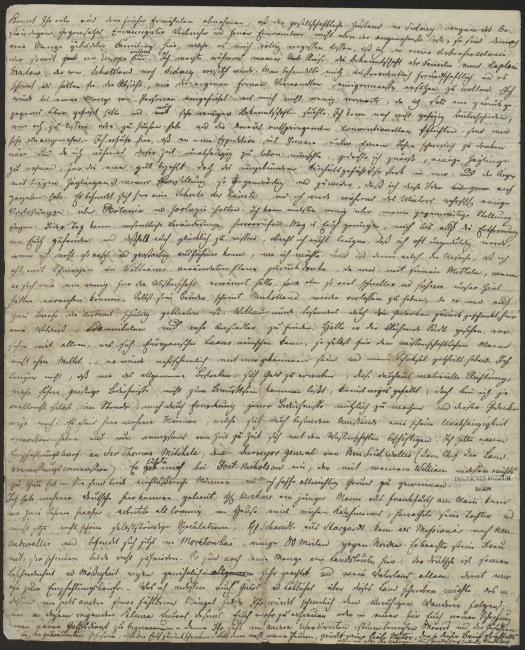

Letter to his brother-in-law Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Sydney (23 March 1842)

Sydney, 23 March 1842

My dearest brother-in-law,

Vast oceans have I crossed, tempestuous storms have I braved. The sun passed over the crown of my head from south to north and now the entire earth lies between me and all of you, now the time of day, the season, indeed the character of the constellations is different, the south is cold, the north is hot, and the shadow that my body casts at noon falls to the south. I left London on the first of October, 1841; we encountered uncommonly stormy weather between London and Cork; yet the desire to see distant lands was so great that we ignored all dangers and hardships and, shielded by coats and sails, blithely sang songs into the moonlit nights surrounded by the bluster of the storm and the roar of the ocean. Oh, if I could express in words to you how deeply the great spectacle of the ocean’s nature moved me! Pinned to the clear sky, the magnificent constellations rose in the east above the sharp line of the horizon, strode in their exalted serenity across the tossing ocean and gradually sank down in the west. As we approached the equator, the old familiar constellations vanished and unseen, more brilliant ones welcomed us. — Our ship, such a frail work of human hands, often occupied my thoughts and commanded my admiration. About 300 people floated over a fathomless, barren expanse toward a distant home with a feeling of complete security and surrounded by many comforts of life, and for its part this small, populated speck, thrown about by wind and weather, was guided by a compass, a piece of iron barely 3” long, yet as such the most marvelous iron bridge that spans the widest oceans between one continent and the next. — We saw a number of islands, such as St. Antonio, one of the Cape Verde islands, Trinidad off the coast of Brazil, St Paul between the Cape of Good Hope and New Holland, yet we stopped nowhere. Life on board was peculiar. Besides the 250 emigrants, there were 20 independent passengers on board. We almost lived like a family with one another since we ate breakfast and lunch and took tea together; yet we remained separate enough to pursue our own interests in the times in-between. I primarily studied the art of navigation, learned how to determine longitude and latitude, and monitored the changes of the barometer and thermometer. The latter never exceeded 23½ degrees as we crossed the line. In general we suffered more from cold than from heat to the north of the equator and, later on, south of it. Since sailors usually play rough practical jokes when they cross the equator, the captain kept the crossing a secret and we did not know about it until we were already 5° to the south. The sailors customarily baptize passengers who cross the line for the first time, which means that they pour water over them, adorn them with tar beards, etc. — It was inevitable that among 20 people who are constantly around one another various frictions would arise. Moreover, there were some elements among us that that caused continual disquiet. On the other hand this disquiet revealed everyone’s true character and proved of the utmost importance for the study of people. We saw few sea creatures: although the ocean is probably most richly populated, with polyps and crustaceans and worms living at its bottom or having attached themselves to it, and with fish and mollusks traversing its expanses in countless numbers. I often peered from the ship into the ocean, regretting that it was not possible to become more closely acquainted with the wonders hidden some 2–3000 feet below the surface. — Nevertheless, schools of dolphins frequently delighted us, half of their bodies surfacing out of the water; they made their appearance particularly before stormy weather—or the cautious shark, which circled our ship in slow motion and instantly and greedily seized any refuse thrown over board. We spotted and captured large numbers of sea birds, especially the albatross, which with its wingspan of 10 to 12 feet appears to live constantly on the wing, hundreds of miles away from land, resting between the crests of waves at night. 4 ½ months went by (Oct., Nov., Dec., Jan., and ½ of Feb.), before we passed through the two cliffs that form the entrance to Port Jackson. When the pilot approached the ship on a boat rowed by New

Zealanders, I wanted to hug the old, olive-colored cantankerous child of the sea as the first herald of a new world. Port Jackson is a broad estuary full of bays, enclosed by hills and cliffs, which were covered in newly greening trees, thanks to a much longed-for rain, and through which we glimpsed friendly-looking homesteads and mansions all around. For almost 18 months the area had suffered uninterrupted drought. Thirst had brought herds of sheep and cattle to their knees at dried-out watering places. Two days before our arrival, it had finally begun to rain and it continued to rain for 14 days without ceasing. This rendered the first part of my stay a bit unpleasant, but I bore the discomfort willingly since it considerably changed and improved the appearance of the natural environs. 52 years ago savages who had never before seen a white man had inhabited the shores of this port. Now a large city of 42,000 residents, surrounded on all sides by the mansions of its rich inhabitants, has arisen. It is built partly in a valley, partly onto two mountains, regularly laid out, generally with large houses and wide streets. The sandstone rock that dominates the entire area often shows through in the streets and frequently they themselves were carved out through it. I was welcomed cordially in Sydney, and although major capital is necessary to effect anything useful I do nevertheless hope to accomplish my goals in due time. The climate is extraordinarily mild and agreeable, especially during the present season, during which only sudden changes in the weather give cause for complaint. An amazing amount of activity and excessive speculation predominate in this city. A huge number of ships fill the port, they come and go daily to and from England, China, to New Zealand, Van Diemen’s Land, Port Philip and to various coastal towns. Steamboats depart for Hunter’s River, for Moreton Bay, to and from Port Philipp. Every luxury item, every article of convenience is obtainable in Sydney. Well-maintained roads lead to the various cities that are situated further toward the interior of the continent, such as Bathurst on the other side of the Blue Mountains, about fifty miles from Sydney, Liverpool, Windsor on the Hawkesbury River, and so forth. And who brought about these incredible transformations in so short a time? — In 1788, Arthur Philipp brought 850 convicts here, founded the colony, and began to reclaim this land with convict labor. Since that time convicts have been continually sent here, used for public construction projects, or assigned as servants to free settlers. Convicts who had served their full sentence were freed and settled down themselves, indeed even under conditional pardon they were allowed to purchase goods and amass independent riches. The wealthiest men of the colony were convicts or are descendants of convicts. But gradually more and more free settlers have been immigrating and by now about 100,000 reside on Australian soil. Almost all of these emigrants are motivated by the desire to amass a fortune. They plan to devote a few years of their lives to this business in order that they can thereafter return to their homeland and spend the days until their death in quiet enjoyment. Few come here to stay: yet many change their plans once they have become better acquainted with the beauty of this rich country and learn to better tolerate its discomforts. These families of free settlers, who take an interest in the colony and regard it as their home country, are the land’s sole true treasure and they will develop into a mighty people who might outshine old Europe. — In the meantime it is only natural that the current social conditions in Sydney cannot be satisfactory since the community is composed of such inharmonic elements. In the company of former convicts even the most liberal persons cannot help but remember that they are interacting with people who were once capable of committing grave offenses. It is true; they have served their sentence and have reentered society with a clean slate—yet have they truly been rehabilitated, do they deserve our trust? Such considerations, which are surely not without merit, have frequently led the free settlers to regard themselves as a separate and better class—and this attitude has unified the emancipated convicts on the other

side, so that now two parties, two predominantly hostile communities face each other, which hinders the progress of the colony. — In past times, whenever a convict ship arrived at Sydney anyone in need of domestic servants stepped forward, and the number of convicts handed over to the new owners depended on the size of their businesses. The owners had legal custody and great control over these convicts, which they abused frequently. The big advantage was that they did not have to pay anything for these convicts and only had to supply them with food and clothes. — Later, meanwhile, when it was recognized that one should not allow the scum of Europe to be sent to this budding colony anymore, the system of assigning convicts to colonists was abandoned and other convict colonies were founded at Moreton Bay (more to the north) and on Norfolk Island. The former has now been opened to free settlers as well. — When a convict had completed his punishment, meaning that he had suffered servitude for 2 or 3 up to 20 or more years, and if had behaved well, he received a permit and could then pursue his own business under police supervision—with the qualification that another misstep would lead to renewed servitude or imprisonment. Only a few obtained unconditional freedom, and there are wealthy men and heads of families in Sydney who are convicts released on conditional pardon only. Since I have left my native country, I have never felt as at home as I do here. One of my traveling companions was a music teacher, a young married man with no children who was following his brother-in-law to Sydney. Upon his arrival here, he rented a house for the enormous sum of 100 dollars per annum, and since he had a spare room, he invited me to live with him to help him with a share of the expenses. I accepted, my room was furnished simply yet comfortably, and in this way I lived exceptionally contentedly under the circumstances, completely absorbed in my studies. For it has a definite fascination for me to watch this newly developing people, which perhaps in less than a century, much like the United States of America, will break free from England to form an independent state or confederation of states. In such a mild climate, with such a bounteous nature, and under conditions so conducive to trade an energetic people like the English cannot help but achieve greatness within a short amount of time. In Italy I have often sorely missed such a race and I believe that Italy’s condition will not improve until a peaceful settlement of industrious men from the north should occur.

Fruits are to be had in abundance. All kinds prosper here, from our apples, pears, peaches, figs, and grapes to exotic fruits like pineapples, bananas, and coconuts, whether it be in Sydney, which is rather sandy and infertile, or in the distant settlements and towns toward the interior or on the coast. They are, however, very expensive, as are vegetables, whereas meat is extraordinarily cheap, especially at present. Servants’ wages are exceptionally high and even boys earn 56–60 Rtl . per year in addition to receiving food and clothing. — As a consequence, servants lead very independent lives and you have to watch out that they don’t leave you in the lurch. — From time to time convicts have escaped so as to live freely in the wilderness and to get out of work duties. Sometimes alone, sometimes together, these men have attacked travelers and solitary settlements. They only seize money, watches, and similar valuables; however their raids have never or only very rarely involved bloodshed. These people are called bushrangers and the mounted police are so close on their heels that their ventures are becoming increasingly rare and will soon cease entirely on account of the increasing population. Criminals are now treated here in the same fashion as they would in any of our big prisons. Strictly guarded in prison and prohibited from speaking, they are escorted out to work every morning, whether to erect public structures, to build roads, or to clear woods. They no longer interact at all with the

residents. Although you might think from the foregoing that social life in Sydney is not generally the most pleasant due to the abiding antagonism between emancipated convicts and free settlers, there are still a great many cultured families residing here who allow me to forget completely that I am living in a convict colony and so far removed from Europe. During my passage I made the acquaintance of the family of a Captain Marlow, who had been transferred from Scotland to Sydney. They treated me with exceptional friendliness and it appears that they mean to act as substitutes for my own relatives as much as is possible. They introduced me to a large number of people, which confused me not a little since I have always led a solitary life and only ever sought a few acquaintances. As of yet I am not fully able to distinguish who I should avoid and who I should seek out and find the accompanying conventional duties very unpleasant. — I learned here that an expedition into the interior earlier than next year would hardly be feasible and since I hoped to be self-reliant during this time I first thought about taking on a few pupils, which pays well. Yet the unfettered feeling of freedom is so strong within me and the prospect of potential aggravation caused by indolent pupils so goes against my current hopes that I gave up on this idea. There is an art academy here and I will probably give a few lectures on botany and zoology during the winter months. However, I can say nothing much as regards my current situation. Every day can bring considerable changes. You should be content in the knowledge that aside from the distance between us I am content and therefore also happy, although I do not dispute the fact that I frequently become impatient when I cannot accomplish something as quickly and brilliantly as I might wish. This is why I frequently think back to William’s changed plans with pain, since we could have accomplished our goals much more quickly and securely with his means had he shown the slightest bit of interest in scientific endeavors. Even his brother seems to have already left New Holland, since he has not yet answered my last two letters. Thoughts of finding nothing but wilderness, cannibals and brute settlers here particularly frightened William. Had he seen this prospering city, where any and all desirable European luxuries are at hand and which is, moreover, not even without means for a man of science—he would have most likely accompanied me and shared my fortunes. I do not deny that I do not at all like the general ambition to amass riches, this very material orientation that prevents the desire for higher intellectual pursuits from surfacing; yet perhaps I am capable of making myself useful by awakening these desires, and this thought appeals to me. There are several men here who have gained financial independence through a variety of circumstances and take an occasional interest in scientific matters. I had a letter of recommendation for Sir Thomas Mitchell, the surveyor general of New South Wales (the head of the land survey commission). He introduced me to Doctor Nicholson, who, however, is not at all related to my William. — Both are influential men and I hope to gradually gain a foothold.

I have met several Germans here. Mr. Kirchner, a young man from Frankfurt am Main, arrived here two years ago, worked as a clerk in the house of a wealthy businessman, married his daughter, and now engages in his own quite profitable speculations. Mr. Schmidt of Stargardt came to New South Wales as a missionary and now resides in Moreton Bay, about 80 miles north of here. His wife accompanied him; they both seem to be quite content. And so there are a large number of additional compatriots here. Generally speaking, the German is well-respected on account of his modesty and temperance and my native country alone often suffices as a letter of recommendation. — Whatever good and praiseworthy things I may write about this country, which like any other also has its own obvious shortcomings, you would surely follow in the footsteps of this restless wanderer, to enjoy life to the fullest in this delightful climate or to begin worshipping God anew amidst what would appear to you like a new creation. — Then again, you are standing on the shore of a vast, tempestuous ocean and the dangers alone, the imaginary dangers, would hold you back. So, farewell my loved ones, convey my love to my dear mother, for whom this letter is after all also meant, and all the others.

Most affectionately,

your Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/1.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.