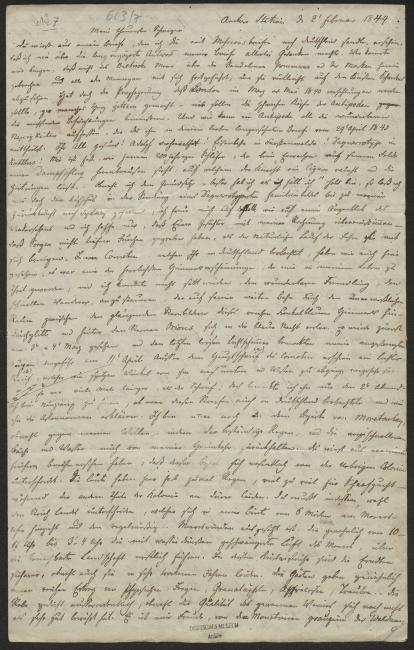

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, the Archer brothers’ Durundur Station, Moreton Bay (2 February 1844)

Archer’s Station, 2 February 1844

My dearest brother-in-law,

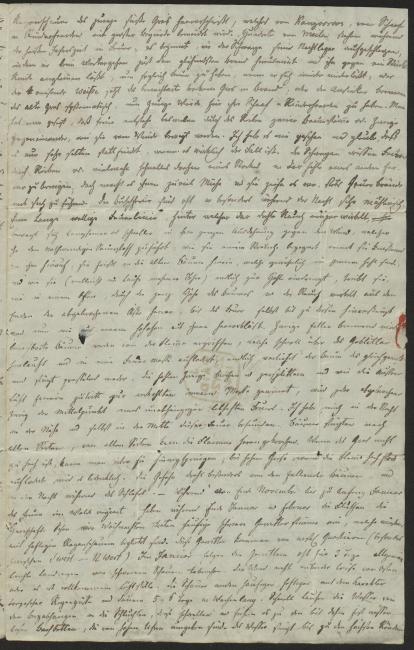

You will learn from my letter—which I sent your way included in missionary letters going to Germany—that I have been worrying quite a bit about the long-delayed answers to my letters. Who could have assured me that the Baltic Sea had not flooded the sandy plains of Pomerania and the March and carried away all my loved ones to deposit them, perhaps, on the coastal areas of Sweden? After all, the prophecy that London was to be swallowed up in March or May of 1840, made many a heart quake—how are the weak minds of the antipodes supposed to master the growing apprehension? And how can an antipodean grasp all the wonderful news of which you inform him in your dear, long-awaited letter of 29 April 1843? All of you healthy! Adolph married! A railroad in Fürstenwalde! Daguerreotype in Cottbus! I almost feel like that 200-year-old sleeper, who, when awaking upon his field, sees a steam-powered plough rushing toward him on which the farmhand smokes a cigar and reads the papers. Although I adhere to the maxim “better to have than to desire,” I acquiesce to your postponing mailing a Daguerreotype family portrait until my return to Sydney; I am looking forward to it as if it were a moment of reunion and I only hope that your faces conform to my reckoning—that sorrows have not carved deeper furrows than the natural passing of time warrants. Here we also saw the comet that you observed in Germany; it was one of the most magnificent celestial phenomena that I have been able to witness in my entire life and I could not get enough of gazing at the wonderful stranger, the fast wanderer, which was gliding on its vast orbit through the unfathomable space between the bright constellations of this deep dark blue sky and was lost to the blue night behind the stars of Orion. It was first sighted on 3 & 4 March and my straining eyes glimpsed the last muted gleam of light on approximately 11 April. Aside from the comet’s main tail (a), a lighter tail (b) appeared, which pointed away from it downwards and westwards at an acute angle; about like this: [small diagram]. It was many times longer than the tail, yet I only noticed it on the second evening. I am curious to learn whether this stripe was observed in Germany as well and how the astronomers explain it. I am still in the Moreton Bay District, although against my will, since the constant rains and the rising streams and waters are preventing me from returning home. You will have learned from my previous letters that this district differs greatly from the rest of the colony. The people here have almost too much rain, far too much for sheep farming – whereas the other parts of the colony suffer from drought. Then again, you have to distinguish the swath of land, about 6 miles wide, that runs along the coast and is exposed to regular ocean winds, which habitually carry saturated ocean air westward across the adjacent landscape between 10–11 and 3–4 o’clock. Along this stretch of coast, harvests are more dependable, although they also suffer during very dry years. The gardens commonly produce a high yield of peaches, figs, pomegranates, apricots, and grapes. — Vines thrive extraordinarily well, although the quality of the resulting wine has not yet proven to be very good. It is a pleasure to rest one’s eyes on the fresh green of vines and peach trees

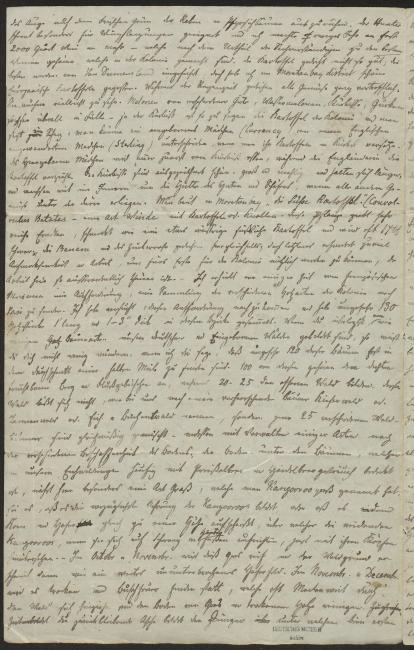

after the woodland’s monotonous gray-green. The Hunter seems especially suited for planting vineyards and last year it produced almost 2000 quarts of wine and then some—which according to the experts are among the best wines produced in the colony. Potatoes do not flourish as much; the best are imported from Van Diemen’s Land; yet I have eaten nice European potatoes in the Moreton Bay district. All vegetables flourish admirably during the rainy season. Perhaps they even grow too much. Melons of varying quality, water melons, pumpkins, and cucumbers sprout everywhere in abundance—indeed, the pumpkin is more or less this colony’s potato and one joke goes: a native-born girl (Currency) can be distinguished from an immigrant English one (Sterling) by serving her a potato and a pumpkin. The native-born girl will first eat the pumpkin, whereas the English girl prefers the potato. The pumpkins are superb, big and mealy, they don’t spoil as quickly, and grow deep inland, around the hut of the herdsman and shepherd when all other vegetables would succumb to drought. In Moreton Bay “the sweet potato” (Convolvulus batatas) is being cultivated—a type of bindweed with potatoes or tubers. This plant produces high yields, tastes like a sweet, somewhat watery potato and often reaches a weight of 17 lb. Bananas and cane sugar also thrive here, yet the latter requires too much attention and work to be beneficial to the colony at the moment, since labor costs are so extraordinarily high here. — Some time ago I received a request from the French Museum to send to Paris a collection of the different types of wood found in the colony. I have tried to fulfill this request and have collected about 130 pieces of wood in this district, 1’ in length and 1–3” in diameter. If you consider how few types of trees form our German and native forests, you will be quite amazed when I tell you that that about 120 of these trees can be found within the radius of half a mile. 100 of these belong to the dense and fertile mountain and river vegetation, whereas 20–25 compose the open forest. Unlike at home, this forest cannot be named pine, fir, or oak or beech forest after the dominant species of tree, but those 25 different forest trees are evenly distributed— however, with some species predominating depending on the composition of the soil; the ground beneath the trees—which is usually covered with lingonberry and blueberry bushes in our oak forests—here nourishes predominantly a type of grass that was named kangaroo grass, either because it is prime nourishment for kangaroos or because, like wheat and oats, it reaches such a height that the grazing kangaroos barely manage stick their heads above it if they sit up on their hind legs and tails. — This grass ripens in October and November and the forest floor then takes on the appearance of a sweeping, continuous oat field. The dry season occurs in November and December and brings with it bushfires, which often extend for miles through the forest and clear its floor of grass and dry wood. The remaining ashes act

as a fertilizer for the young, sweet grass which springs upon the first rain shower and on which kangaroos, flocks of sheep, and herds of cattle graze with delight. Hundreds of miles are covered with fires during the hot season; it starts on the spot where a black man had settled for the night, when, upon his departure, he removes a hotly-glowing stick from his campfire and leaves it smoldering against a piece of tree bark so as to be able to create a new campfire instantaneously upon settling in again; or the traveling white man sets nearby dry grass on fire; or settlers systematically burn the old grass to generate fresh pasture for their flocks of sheep and herds of cattle. I have been told that at times fires are started by two tree trunks or branches rubbing against each other in the wind. I have never witnessed this and believe that this rarely happens, if there is even any truth to it at all. The blacks know to generate fire through rubbing or rather swiftly rotating a stick in the cavity of another; yet they find this too cumbersome and prefer to always carry burning sticks with them. The bushfires are oftentimes very picturesque, especially at night. A long, wavy line of fire, beyond which thick smoke whirls upwards, moves now slowly, now faster along its entire length against the direction of the wind, which feeds it the necessary oxygen; it encounters a shrub and engulfs it, crackling: it eats into the old trees, which are usually hollow on the inside, and as it (perhaps over the course of several years) finally reaches the tree’s cavity, it blows through the entire height of the tree—as it would do in an oven—and smoke curls out of the ends of broken branches until the fire itself reaches them and now blows forth from them as if this were a furnace. Burning branches fall down, and the flames engulf neighboring trees and quickly race across the foliage and flare up in a massive fire. In the end the tree loses its balance and topples over ablaze, its hollow branches break and splinter, and as fresh air gains easier access to the charred materials on the inside every broken branch becomes the center of its own lively fire. At night I have found myself near and even in the middle of these fires. Trees were toppling in every which direction, from all sides flames crept closer. If the grass is not too high one can jump over them; in high grass, when the flames are blazing high, it precarious. The greatest danger comes from toppling trees or when one is asleep at night. — Whereas fire reigns supreme in the forest from the end of November to the beginning of January, floods dominate during the end of January and in February. Frequent heavy thunderstorms occur even before Christmas, which are often accompanied by heavy rains. These thunderstorms hail from westerly areas (especially between S West–N West). In January, light steady rains frequently lasting three days, with intermittent heavy showers, follow in the wake of these thunderstorms. Winds either blow gently from the east or the air is completely calm. The showers then increase in frequency and severity, taking on the character of tropical torrents, and last 5–6 days or for weeks. Water quickly runs down the mountainsides into the ravines, which swell and carry it to the streambeds between high banks that had been almost dry up to this point. The water rises to the top,

spills over, and floods the neighboring plains and hollows. The barely flowing creek is now a magnificent, raging river, which [now] surrounds, erodes, and frequently uproots the thick trunks of trees growing in the riverbed. Yet since the water plunges sharply downwards it drains as quickly as it came and returns to middling levels within two to three days. Traveling now becomes very arduous. The ground is soaked; horses sink in deeply, carts get bogged down in muck that reaches their axles, and fierce gusts of wind more easily uproot tall forest trees, whose roots usually lie shallowly in light soil, which, when soaked by rain, no longer offers sufficient support for the tree. — Usually a sudden strong wind blowing from the west puts an end to this rain. Although wind changes direction from west to north, east, and south in Europe, in New Holland it follows the opposite path, from west to south, east, and north. — This is usually the case, and if it deviates, it usually corrects course back again. In Moreton Bay and Wide Bay I have noticed, however, that easterly winds suddenly change into westerly ones, as if two streams of air were flowing atop one another, of which the upper, westerly one at times sinks down.

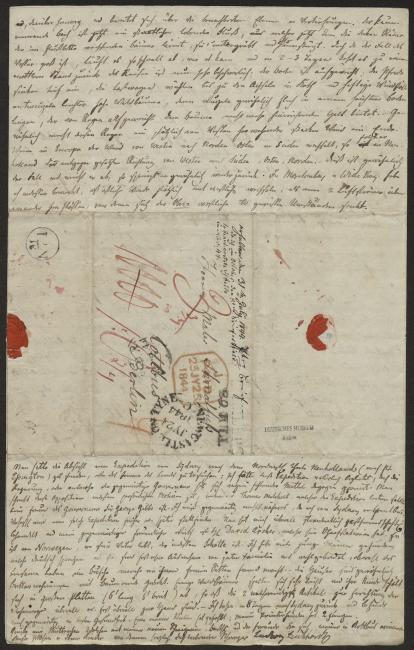

There were plans to send an expedition from Sydney to the northwestern part of New Holland (to Port Essington), to investigate the interior of the country. I would certainly have accompanied this expedition, yet the government, or rather the present governor, opposed it on the grounds of insufficient funds. However, this opposition is attributed to personal motives, since Sir Thomas Mitchell, who was supposed to lead the expedition, is no friend of Governor Sir George Gibbs. As I am away from Sydney, I know nothing more concrete about this at the moment. It is likely that such an expedition will take place sooner or later. Everywhere I enjoyed the utmost hospitality and my present friendly host is Mr. David Archer, who owns sheep stations here. He is from Norway, where his father lives, who, however, is a Scotsman. I have encountered many young men who speak German and who, almost without exception, come from good families and are well-educated, although the lonely life in the bush has made some of them forget their good manners. Houses are commonly rough-hewn shacks covered with tree bark. A number of forest trees are easily split and their bark peels off in large sheets (6’ long, 6’ wide), so that the two utmost necessities for the construction of dwellings are at hand everywhere, or just about everywhere. — I will return to Sydney in 8 days and am currently in the best of health. One of my mares had a foal; my pointer bitch had 2 young pups.

Convey my greetings to dear mother, to Adolph and my new sister-in-law, to the Barths and to those friends in Cottbus who remember me. Greetings to Fettchen and your children from your loving brother-in-law,

Ludwig Leichhardt

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/7.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.