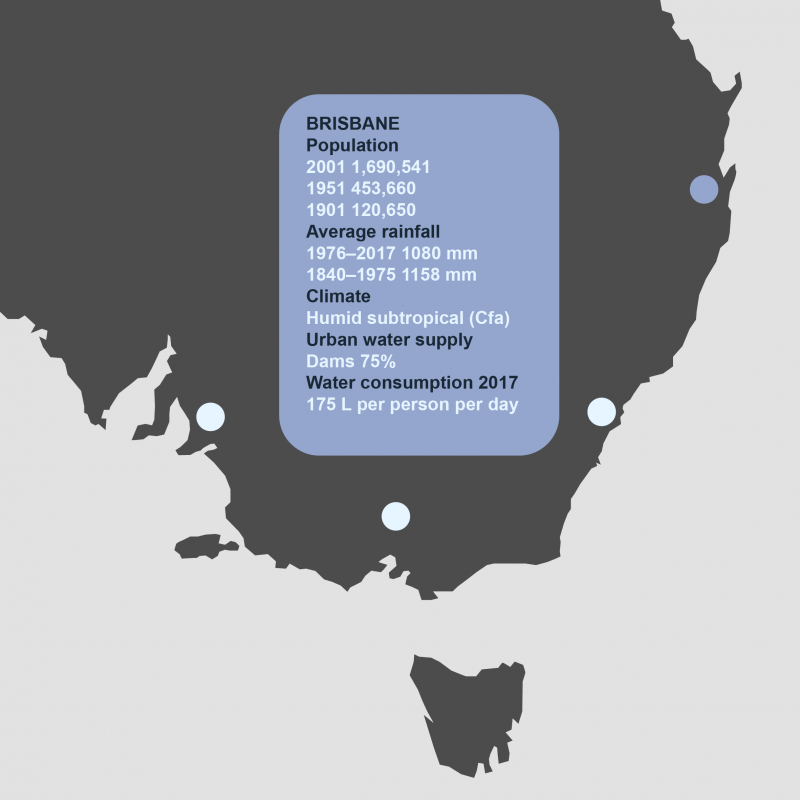

Brisbane: Dams and the Subtropical Challenge

Map by Nathan Etherington

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Brisbane (Meanjin) is the only capital city in Australia built on a floodplain, and the only large metropolitan area to experience major flooding. Its subtropical climate is characterized by summer rain and comparatively dry winters. Brisbane, with an average rainfall of 1149 mm, is the third wettest capital city after Darwin and Sydney.

Established as a British penal settlement in 1824, on land appropriated from the Aboriginal Turrbal and Jagera peoples without treaty or compensation, the infant city suffered a major flood in 1841, with the high water level at 8.43 meters, inundating most of the built-up area. Despite this lesson, the new town embraced the river, filling its floodplain with homes and businesses. With each successive decade of urban growth, the flood hazard grew and the potential damage bill expanded. While engineering structures mitigated the floods, nature would prove that they could not be prevented: Brisbane continued to experience major flooding.

The 1893 Flood

In 1892–93 Queensland experienced severe drought in the western districts. Relief came with an especially wet season in 1893, from what is now understood to have been a forceful La Niña event. Over 1,025 mm fell in February alone, causing three floods in the Brisbane River (Maiwar), two of which were over eight meters high.

These floods claimed 35 lives out of a population of 100,000. An estimated 350 hectares in South Brisbane and 130 hectares in North Brisbane were submerged. The Indooroopilly and Victoria bridges were destroyed, leaving the city without a cross-river bridge for two years. Water subsumed almost two-thirds of the Brisbane business district, reaching 4.8 meters deep in places, lapping verandah tops. In South Brisbane, only the roofs of buildings could be seen, peeking out of miles of unbroken water. February’s Town and Country Journal reported that Stanley Street, South Brisbane’s main thoroughfare had become “one long stretch of ruin and desolation.”

Brisbane is flooded by the second and third highest recorded floods within a fortnight. Unknown photographer, 1893.

Brisbane is flooded by the second and third highest recorded floods within a fortnight. Unknown photographer, 1893.

Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland. Image 84890. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The river’s floodwaters ignored class distinction, with the Maryborough Chronicle reporting that “cottage, bungalow, and mansion” vanished equally under the floodwaters. Railway lines and roads were destroyed and the port closed. As fears rose about the threatened water supply, Brisbane was left without gas and electric light. The floods created enormous social problems, including homelessness, destitution, hunger and unemployment.

Flood descriptions portray a sensory overload. Newspapers recounted the noise —the roar of the floodwaters, the crash of debris and “heart-rending screams.” Journalists recorded the devastation and suffering vividly. Smell overwhelmingly dominated settler recollections, with typical accounts referring to the “terrific” stench of the receding flood and the “foul-smelling mud.” The miasma of floodwaters and mud in Queensland’s February sub-tropical heat, full of dead animals, debris, and raw sewage, would no doubt have been memorable.

The central businesses of Brisbane lay under water during the 1893 floods. Photograph by Paul Poulsen, 1893.

The central businesses of Brisbane lay under water during the 1893 floods. Photograph by Paul Poulsen, 1893.

Courtesy of State Library of Queensland. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The 1893 floods accelerated a program of engineering interventions that included dredging the river, truncating bends, building training walls, and ultimately the decision to build Somerset Dam in the early 1930s, even though its completion took another twenty-five years.

The Australia Day Floods, January 1974

In the La Niña year of 1974 Queensland received an estimated 900,000 million tons of rain in January. As Brisbane prepared for its annual Australia Day public holiday on 26 January, a large monsoonal trough, associated with Cyclone Wanda, hovered above the 13,500 km² Brisbane River catchment.

Floods inundated central Brisbane in 1974. Unknown photographer, 1974.

Floods inundated central Brisbane in 1974. Unknown photographer, 1974.

Image courtesy of the State Library of Queensland. Click here to view source.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

A slow moving rain depression dumped huge amounts of rain, flooding local creeks and the Bremer River tributary upstream in Ipswich. Brisbane experienced three separate intense rain events, with record rain of 600 mm falling over three days. On 26 January Brisbane received 314 mm of rain, only the second recorded time the average monthly rainfall was exceeded in 24 hours and the city’s wettest day in 87 years. The capital braced itself for riverine floods. On 29 January the river peaked at 5.45 meters in Brisbane city, the largest floods since 1893 (8.35 m and 8.09 m).

Spectators watched in awe as the turbulent river raced at 22–25 km per hour towards Moreton Bay. The Courier-Mail and Sunday Mail offered graphic descriptions: “houses were swept into raging floodwaters,” “ripped off their stumps, steel walls of factories were torn open, and luxury craft were smashed to matchwood.” The river—now more than three kilometers across at its widest, having swelled into its floodplain—submerged or destroyed everything in its path. Upstream, land lay inundated up to nine meters, leaving buildings submerged to roof height for up to three days.

Men rescue beer from a flooded brewery in Brisbane during the 1974 floods. Unknown photographer, 1974.

Men rescue beer from a flooded brewery in Brisbane during the 1974 floods. Unknown photographer, 1974.

© Brisbane City Council.

Courtesy of the Brisbane City Council Archives.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Floodwaters cut across highways and railway lines and closed the airport. Only one bridge over the river remained open, streets became canals, and Brisbane became largely isolated. Flooded suburbs were left without gas, and electricity supplies were thwarted, with suburban substations and the main power station inundated. Forty kilometers upstream in Ipswich, coal production ceased, with stored supplies left rain-soaked.

Raw sewage from the submerged Ipswich sewerage plant and domestic outhouses poured into the river. Debris, chemical contaminants, dead fowl, horses, and cattle floated in the floodwaters, increasing the public’s risk of gastroenteritis and tetanus. As the flood waters receded, they left behind layers of disease-carrying sludge, and the rancid smell of mud and effluent permeated the air.

The floods claimed 14 lives in Brisbane and affected 13,000 homes in 30 suburbs that were left submerged, inundated, or damaged, in a city of 712,500 people with 217,847 dwellings. People wept openly in the streets as they returned to the shells of their homes to find their possessions ruined, or their homes damaged beyond repair. With agricultural land rendered unproductive and food left rotting in the Brisbane Markets, the community faced food shortages. Numerous industries, shops, and businesses struggled to resume work, threatening the viability of businesses and the livelihoods of their employees. The cost of damage was estimated at a crippling AUD $178 million.

Many people dealing with flood damage struggled to comprehend why they had been flooded, despite living on a floodplain. To their mind, Somerset Dam had failed to withhold the floods. But relief was seemingly at hand, as the Bjelke-Petersen state government had implemented plans for a second dual-purpose, flood migration and water supply dam, Wivenhoe, which was completed in 1984. This dam, residents hoped, would finally floodproof Brisbane.

2011 Flood: It Happens Again

After almost a decade of drought, water levels in Southeast Queensland’s dams had plummeted to frighteningly low levels. In late 2010 Australia entered the strongest La Niña period since 1974. By 5 January 2011, record-beating rainfall had flooded more than 78 per cent of Queensland, 1 million square kilometers (an area greater than France and Germany combined). Worse was to come between 10 and 12 January, as 1000mm fell in the Brisbane River catchment within 48 hours. Townships were almost obliterated by floodwaters on 10 January and the floods took 16 human lives. The floodwaters raced towards Brisbane, reaching heights of 4.46 m at the Port Office Gauge.

Floodwaters and debris inundated suburban homes in the 2011 Brisbane flood. Photograph by John Doody, 2011.

Floodwaters and debris inundated suburban homes in the 2011 Brisbane flood. Photograph by John Doody, 2011.

John Doody, Brisbane, Australia, 2011.

Accessed via State Library of Queensland on 14 March 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Brisbane’s central business district became an archipelago, with 22 streets and hundreds of buildings inundated. Businesses closed for five days, unsettling the local economy. In all, 14,100 Brisbane properties were affected across 94 suburbs, with 1,203 houses flooded: moreover, 1,879 businesses were partly and 557 completely inundated. As floodwaters receded, Brisbane again lay buried in mud, dead animals, decaying vegetation, and sewage, which created a foul-smelling miasma that permeated nostrils, clothing, and memory.

State Premier Anna Bligh later acknowledged that “it felt that all our knowledge, our science, our preparation, and experience might be useless in the face of Mother Nature’s new and incomprehensible behavior.” Yet floods were not “new.” Since British colonization Brisbane had experienced four large floods (in 1841, twice in 1893, and in 1974).

The completion of Somerset Dam in 1959 and Wivenhoe Dam in 1984 had deluded many into thinking that Brisbane had been flood-proofed. While the dams reduced the flood height by 2 m, decades of building on the floodplain had greatly increased the flood damage, a bill that reached 3 billion Australian dollars. The flawed dependency on flood mitigation dams made the floods seem “incomprehensible,” rather than a naturally occurring event.