Introduction

The US’s militarized landscapes—which include offshore bases, testing and training facilities, former war zones, and waste disposal sites—have exposed communities worldwide to a range of health risks. With bases scattered throughout the world, the US exposes vulnerable populations to environmental ills ranging from noise pollution and toxic dumping to radioactive exposure, sexual violence, and accidental civilian deaths. Because these consequences are dispersed across great distances and generally concentrated in foreign and less powerful places, many Americans are unaware that the US Department of Defense is one of the world’s largest polluters. This online exhibition focuses on artworks and other representational media that attempt to educate audiences about these issues by depicting places and populations subject to environmental harm spread by US military activities. By considering responses to militarization in locations such as Puerto Rico, Guantánamo Bay, Guam, Hawai’i, the Marshall Islands, South Korea, Iraq, and the US Southwest, this exhibit draws comparisons and connections between disparate geographical locations and cultural contexts. Across the globe, military tests and bases confront vulnerable groups with common problems: how to generate evidence for the risks they live with, how to represent risks in terms that translate beyond local contexts, and how to forge alliances with other groups in order to resist the larger systemic forces that underlie militarization.

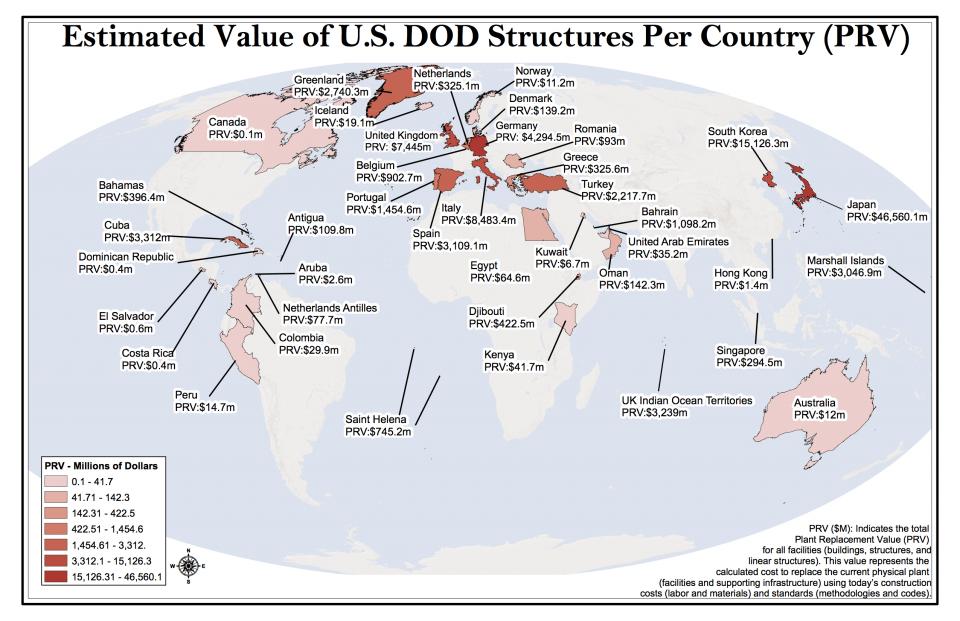

Map showing the estimated value of US Department of Defense structures per country (Plant Replacement Value), 2013

Map showing the estimated value of US Department of Defense structures per country (Plant Replacement Value), 2013

Created by Kareem Shihab (2013)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Risk and the landscapes of US militarization begins with historical overviews of militarized locations such as bases, testing and training sites, and former war zones stretching across the globe. These locations graphically demonstrate war’s environmental entanglements, particularly in recent decades as military targeting has shifted from enemy bodies to infrastructure and environment (Mbembe 2003; Sloterdijk 2009). In addition to detailing the scope of militarization and some of the health effects suffered in the presence and aftermath of bases, military exercises, and war, this exhibit outlines responses by local anti-militarization movements. These movements are notably diverse, bringing together first-time protestors, experienced organizers, activists representing a range of interests, and people from different social classes, ethnic groups, and geographical locations (Hardt 2012). Some anti-militarization struggles have even “generated new practices of democratic political organizing, linked to other local social movements” (Hardt 2012, 826). At the same time, local movements have built coalitions across regional and national boundaries, laying the groundwork for demilitarization and environmental justice on a global scale.

After documenting the environmental harm wrought by US bases, this exhibit goes on to consider how specific forms of representation have been used to legitimize or resist militarization and its attendant risks. Activists have drawn on the distinctive qualities of media such as maps, documentary film and video, monuments, popular films, novels, photographs, and site-specific performances to convey the social, psychological, and biological effects of living in militarized places. In addition to providing an overview of how environmental and anti-militarization movements have deployed different art forms and media, the second half of this exhibit aims to better understand what specific cultural forms can contribute to the projects of representing and redressing environmental risks.

These forms of cultural resistance, often produced outside the US, are of critical importance in the context of the “military normal” that deploys censorship, news media, the entertainment industry, recruiting advertisements, and consumer goods to celebrate US militarization while obscuring the forms of violence that it propagates at home and abroad (Lutz 2009). Although most of the damage caused by the US Department of Defense is borne by poor and nonwhite subjects located beyond the nation’s boundaries, inhabitants of the US and the Global North are also at risk. Radiation poisoning in the US Southwest, veterans affected by depleted uranium and Agent Orange, and the ongoing epidemic of civilian gun-related violence attest to the domestic costs of militarization. As the world’s largest oil consumer (360,000 barrels per day in 2010), the Department of Defense is also responsible for a considerable share of global greenhouse emissions, as well as the oil dependence that has partially motivated recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (Karbuz 2011). Although the landscapes of US militarization distribute damage, risks, and security unevenly, we all inhabit them to some extent. I hope that the works presented in this exhibit will advance our understanding of the environmental impacts of militarized spaces, and suggest new ways to reclaim them.

Bibliography:

Hardt, Michael. “Note from the Editor, Struggles against US Military Bases.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111, no. 4 (2012): 826.

Lutz, Catherine. “The Military Normal: Feeling at Home with Counterinsurgency in the United States.” In The Counter-counterinsurgency Manual: Or, Notes on Demilitarizing American Society, edited by the Network of Concerned Anthropologists, 23–38. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2009.

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11–40.

Karbuz, Sohbet. 2011. “How much Energy Does the U.S. Military Consume.” The Daily Energy Report, 3 January 2011.

Sloterdijk, Peter. Terror from the Air. Translated by Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter