Bases

Unified Command Plan—world map showing US combatant command areas of responsibility

Unified Command Plan—world map showing US combatant command areas of responsibility

Source: Washington, DC: US Government—National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, 2011

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

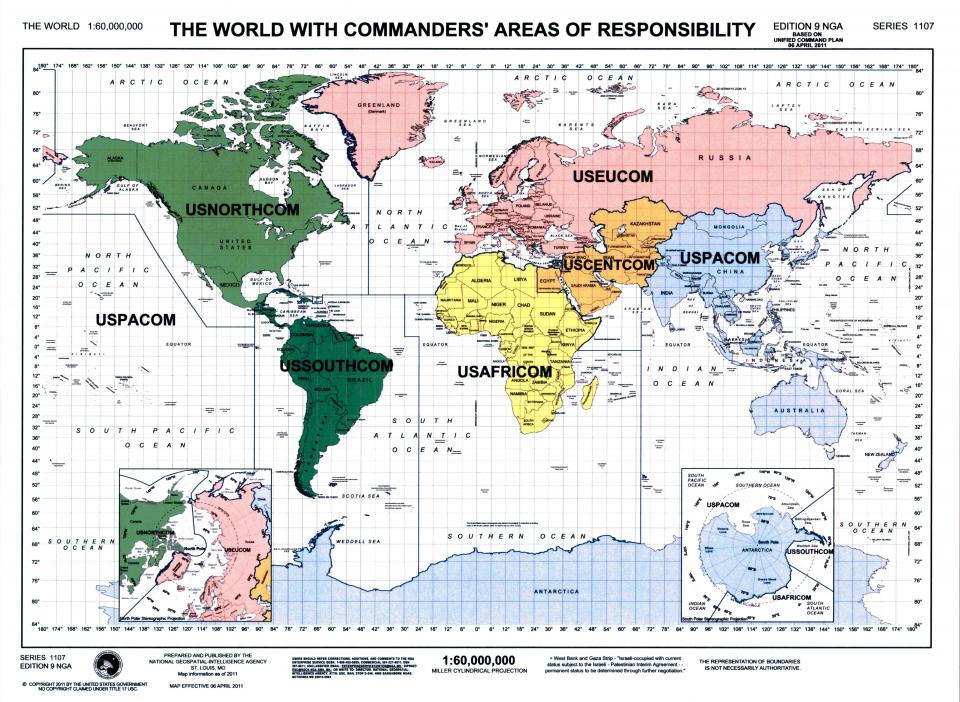

The twentieth century witnessed the construction of a vast network of US bases, which project military power across the entire globe. Since the US acquired its first set of foreign military bases (frequently used as heavily polluting coaling stations) following the War of 1898, new bases have been built or acquired with each war, and new weapons have resulted in the opening of diverse testing and disposal areas. From 1898 to the Cold War and the contemporary “war on terror,” US military bases have spread to 63 countries and to every continent except Antarctica. According to the US Department of Defense’s 2012 Base Structure Report, the US operates 760 bases outside of the nation’s boundaries: 666 foreign bases and 94 in unincorporated territories. With its domestic and worldwide holdings of 2,202,735 hectares as of 2007, the Pentagon is one of the world’s largest landowners (Dufour 2007). Bases located outside the US include 114,571 buildings and other physical structures. As growing antibase movements have demonstrated, these bases impose catastrophic environmental and cultural costs on local communities. For example, the negative impacts of bases in South Korea include “environmental damages, including contamination of water, soil, and air by hazardous wastes and spills; deafening noise and debilitating vibration from repeated military exercises; spatial constraints on planning and development of a host community; GI crimes against local residents; and camptown prostitution” (Moon 2012, 865).

US military bases on the Japanese island of Okinawa

US military bases on the Japanese island of Okinawa

Created by Misakubo, 2010.

View source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

One of the most heavily militarized sites—the Japanese island of Okinawa—exemplifies how US bases transform not only spaces, but also local economies and lives. Connected by the island’s roads and highways, US bases, firing ranges, training areas, and military resorts occupy 18 percent of the land on Okinawa’s main island—“perhaps as much as 25 percent in the most densely populated areas….” (Nelson 2012, 828). The effects of this buildup are profound. Drawing on his years of field research in Okinawa, the anthropologist Christopher Nelson (2012, 828) writes that “this massive complex of bases…intrudes on the most public and the most intimate moments of everyday life, shaping the memories, thoughts, dreams, and actions of those who dwell there.”

Okinawans have long protested US military presence, particularly after three marines raped a 12-year-old Okinawan girl in 1995. In response to an international coalition of protestors, the US and Japan have made plans to move the Futenma airbase; however, this would only move the military buildup from Futenma to other populated areas such as Guam and the Okinawan village of Henoko. Although protestors managed to delay the construction of an airbase at Henoko by conducting an extended sit-in and by citing its effects on the marine ecosystem and endangered sea mammals (the dugong), in April 2013 Japan’s prime minister Abe Shinzo and the US ambassador to Japan jointly announced plans to construct a new US base at Henoko by 2022.

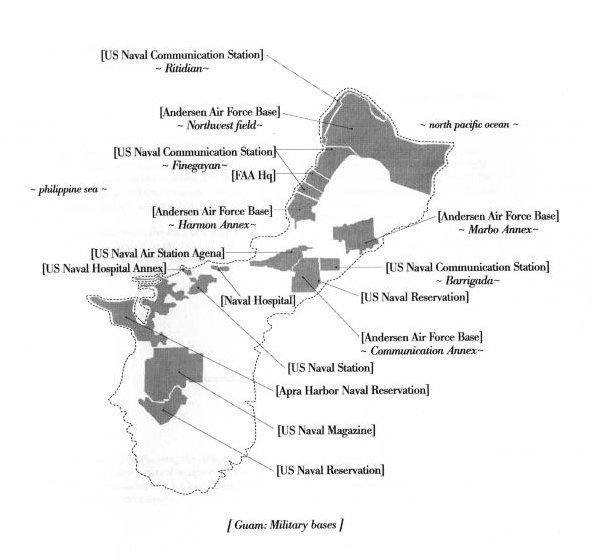

Plans to transfer around 5,000 marines from Okinawa to Guam just shift the problem somewhere else—in this case to an island already overwhelmed by US military presence. Bases and other military sites account for one third of Guam’s territory, and the island’s disenfranchised status as an “unincorporated territory” of the US makes it difficult for its indigenous Chamorro inhabitants to resist further military buildup. In addition to the manifold environmental impacts of colonialism and military bases, Chamorros are faced with few economic alternatives besides working for the military bases and tourist resorts that occupy and poison their island. The Department of Defense calculates that new military buildup will bring 41,194 new residents to Guam by 2016—an immense figure considering that the 2010 census counted 159,358 residents in Guam. The militarization of Guam’s landscape, economy, and culture has already made many Chamorros dependent on the US military, which is by far the island’s largest employer; Chamorros rank first by both geographic region and ethnicity in US military recruitment rates (Hsu 2009, 286). The disproportionate number of deaths suffered by soldiers from Micronesia (including Guam) in the Iraq War “are jarring considering that the population of this region of the world is less than six hundred thousand and that close to half of those who have served and died from Micronesia are not U.S. citizens and would not even be considered ‘semi-Americans’” (Bevacqua 2010, 50).

Camp Justice, Diego Garcia

Camp Justice, Diego Garcia

Photo taken by US federal government employee John Dendy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The island of Diego Garcia, located in the Indian Ocean, provides a dramatic example of the violent displacements that frequently clear the ground for US military activities. The island—which the US has leased from Great Britain since 1966—has been used to stage military operations in the Middle East and allegedly houses both nuclear weapons and a “black site” for detained prisoners. To make space for “one of the most important bases in the world,” the US and Great Britain displaced approximately 2,000 Chagossian islanders from Diego Garcia to Mauritius and the Seychelles (Vine 2012, 847). Recently, as the Chagossians fought in European courts for the right to resettle in their homeland, a Wikileaks cable revealed that US and British officials colluded to prevent their return to the archipelago by establishing “the world’s largest marine protected area (MPA) in the Chagos Archipelago. The MPA banned commercial fishing and limited other human activity, endangering the viability of any resettlement efforts” (Vine 2012, 854). The MPA cynically appeals to the notion of environmental “protection” to deny Chagossians’ right to return to their homeland and to consolidate a network of military bases that devastates natural and social environments worldwide.

A global network of antibase and anti-militarization activists has long struggled to diminish or abolish the US’s foreign bases. Its successes include the 1991 agreement to remove all permanent US bases in the Philippines and the closure of an ordnance training base in Vieques, Puerto Rico, following the accidental bombing of a civilian custodian. In addition to local base closures, antibase movements have created and strengthened coalitions that cut across geographical and social boundaries: for example, Al Sharpton and Rev. Jesse Jackson participated in Vieques protests, a group of Japanese and American activists filed suit against the Department of Defense in the US District Court of Northern California to protect Okinawa’s coast from base expansion, and organizations such as the Campaign for the Accountability of American Bases (www.caab.org.uk), the international No Bases Network, and the People’s Task Force for Bases Cleanup attempt to organize local antibase and base cleanup struggles on a global scale.

Bibliography

Bevacqua, Michael Lujan. “The Exceptional Life and Death of a Chamorro Soldier: Tracing the Militarization of Desire in Guam, USA.” In Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, edited by Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho, 33–62. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Department of Defense. Base Structure Report, Fiscal Year 2012 Baseline. Washington, DC, Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, 2012.

Dufour, Jules. “The Worldwide Network of US Military Bases.” Global Research, 2007.

Inoue, Masamichi. Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Kelman, Brett. “Report: Guam Buildup to Happen More Slowly.” Navy Times, August 5, 2010.

Moon, Seungsook. “Protesting the Expansion of US Military Bases in Pyeongtaek: A Local Movement in South Korea.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111, no. 4, (2012): 865–76.

Nelson, Christopher. “Occupation without End: Opposition to the US Military in Okinawa.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111, no. 4 (2012): 827–38.

Vine, David. Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Vine, David. “What If You Can’t Protest the Base? The Chagossian Exile, the Struggle for Democracy, and the Military Base on Diego Garcia.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111, no. 4 (2012): 847–56.