Tributaries of Radical Environmentalism before Earth First!

The event that precipitated the formation of Earth First! was a devastating defeat in the late 1970s at the end of the US Forest Service’s “Roadless Area Review and Evaluation” process, in which the Forest Service refused to grant the designation of “wilderness” to areas that many conservationists considered biologically important. But the seeds of radical environmentalism had already sprouted long before then. As early as the 1950s there were scattered incidents of sabotage in the United States in defiance of environmentally destructive and aesthetically displeasing commercial enterprises. Some of these were reflected in the writings of the Southwestern writer Edward Abbey, first subtly, in his classic memoir Desert Solitaire (1968).

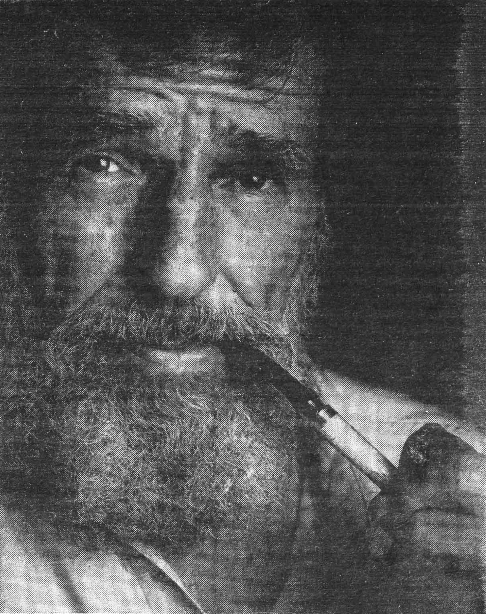

Edward Abbey. See Earth First! 9, no. 5.

Edward Abbey. See Earth First! 9, no. 5.

© Earth First! Journal

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In it, while ruminating on his time as a park ranger at Utah’s Arches National Monument (now a national park), Abbey alluded to late-night sabotage campaigns by wilderness lovers that had begun in the late 1950s. Soon Abbey published The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), a novel about a band of passionate if crazed and angry environmentalists who roamed the deserts of the Southwest, destroying billboards, bulldozers, and conspiring to blow up Arizona’s Glen Canyon Dam to liberate the Colorado River, which they felt had been unjustly incarcerated behind it. Abbey combined evocative, pantheistic writing about the sublime value of nature, with a unique form of libertarian anarchism that resonated with biocentrism, and by so doing, inspired many of those who formed Earth First! Earlier nature writers, especially Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and Aldo Leopold, also helped to kindle the movement, as did a host of writers who from the 1960s onward provided strong critiques of mechanistic, hierarchal, patriarchal, monotheistic, agricultural-industrial-capitalist societies, especially Rachel Carson, Paul Shepard, Louis Mumford, Lynn White Jr., and Roderick Nash.

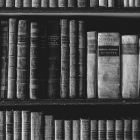

The original exhibition includes and interactive gallery of authors and books that have inspired the Earth First! movement. View the items on the following pages.

Abbey, Edward. The Monkey Wrench Gang. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1975.

When the cities are gone, he thought, and all the ruckus has died away, when sunflowers push up through the concrete and asphalt of the forgotten interstate freeways, when the Kremlin and the Pentagon are turned into nursing homes for generals, presidents and other such shitheads, when the glass-aluminum skyscraper tombs of Phoenix Arizona barely show above the sand dunes, why then, why then, why then by God maybe free men and wild women on horses, free women and wild men, can roam the sagebrush canyonlands in freedom—goddammit!—herding the feral cattle into box canyons, and gorge on bloody meat and bleeding fucking internal organs, and dance all night to the music of fiddles! banjos! steel guitars! by the light of a reborn moon!—by God, yes! Until, he reflected soberly, and bitterly, and sadly, until the next ice age and iron comes down, and the engineers and the farmers and the general motherfuckers come back again.

— Edward Abbey in The Monkey Wrench Gang

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden; or, Life in the Woods. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

— Henry David Thoreau in Walden.

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1949.

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.

— Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will ensure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.

[…]

A Who’s Who of pesticides is therefore of concern to us all. If we are going to live so intimately with these chemicals eating and drinking them, taking them into the very marrow of our bones - we had better know something about their nature and their power.

— Rachel Carson in Silent Spring

Snyder, Gary. Turtle Island. New York: A New Directions Bookm, 1974.

“Goal: Clean air, clean clear-running rivers, the presence of Pelican and Osprey and Gray Whale in our lives; salmon and trout in our streams; unmuddied language and good dreams.”

— Gary Snyder in Turtle Island

Donella H. Meadows et al. The Limits to Growth, New York: Universe Books, 1972.

People don’t need enormous cars; they need admiration and respect. They don’t need a constant stream of new clothes; they need to feel that others consider them to be attractive, and they need excitement and variety and beauty. People don’t need electronic entertainment; they need something interesting to occupy their minds and emotions. And so forth. Trying to fill real but nonmaterial needs-for identity, community, self-esteem, challenge, love, joy-with material things is to set up an unquenchable appetite for false solutions to never-satisfied longings. A society that allows itself to admit and articulate its nonmaterial human needs, and to find nonmaterial ways to satisfy them, world require much lower material and energy throughputs and would provide much higher levels of human fulfillment.

— Donella H. Meadows in The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update

Authors and books that have inspired the Earth First! movement. Click on the images for a larger format.

Likewise, the tributaries of radical environmentalism included diverse streams of the American counterculture, which incubated in the 1950s and emerged as a powerful cultural force in the 1960s. Its elements included a deep suspicion of, if not outright antipathy towards, the religious and philosophical underpinnings of Western culture, which was said to obviate a proper understanding of sacredness and kinship of all life and to be linked to a repressive patriarchal order. Offered as alternatives, variously, were worldviews rooted in indigenous traditions (especially American Indians), recently revitalized pagan religions, or religions originating in Asia, as well as understandings emerging from ecology and new sciences ranging from quantum and complexity theory to conservation biology and the Gaia hypothesis. These diverse streams were all said to recognize the interrelatedness and mutual dependence of all life and to provide better ethical guideposts than Western civilization with its sky gods, philosophical dualism, and reductionist science. Fused to this were leftist or anarchist political ideologies, and sometimes a corresponding revolutionary fervor, envisioning the overthrow or eventual collapse of a putatively authoritarian and environmentally unsustainable capitalist nation-state.

Binary associations typical of radical environmentalism. Adapted from the article “Radical Environmentalism” in Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, ed. Bron Taylor (London & New York: Continuum, 2005).

Binary associations typical of radical environmentalism. Adapted from the article “Radical Environmentalism” in Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, ed. Bron Taylor (London & New York: Continuum, 2005).

© Bron Taylor 2017

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

No one better exemplified or promoted the general thrust of these critiques than the poet/philosopher Gary Snyder, who had been deeply involved in the San Francisco counterculture. In his remarkably innovative (and eventually, Pulitzer Prize-winning) book of poetry and prose, Turtle Island (1969), Snyder advanced an animistic and biocentric spirituality influenced by American Indian cultures and shaped by his long-standing Buddhist practice. He fused these spiritual views to a decentralist, anarchist ideology inspired by Petr Kropotkin and the International Workers of the World (a.k.a. the Wobblies) that he and others innovatively labeled Bioregionalism, which sought to reconfigure political loyalties and revive a sense of connectedness with the watersheds and ecosystems people inhabit and to which they belong. This mix of nature-based spiritualities and decentralist political ideologies was a close countercultural cousin to Earth First!; the bioregionalists focused on creating environmentally sustainable and spirituality meaningful communities while Earth First!ers prioritized direct resistance to what they also considered the destructive force of Western civilization.

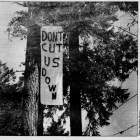

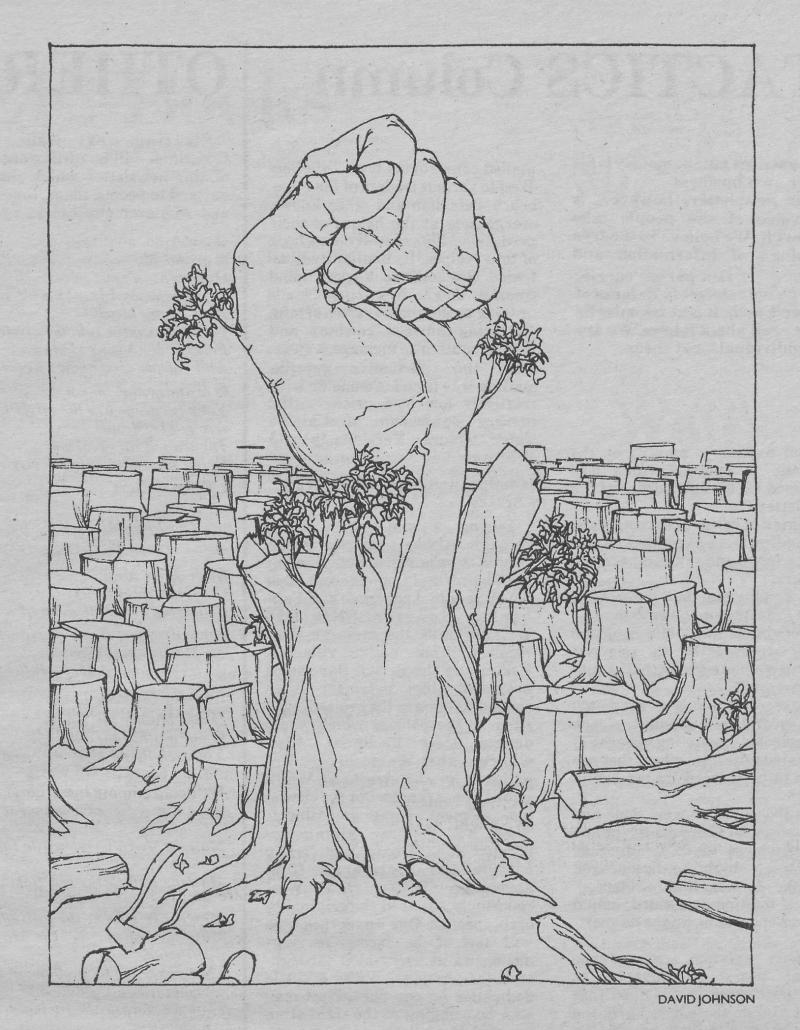

An Earth First! Tree. See Earth First! 2, no. 3.

An Earth First! Tree. See Earth First! 2, no. 3.

© David Johnson

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Although there were differences and sometimes tensions between members of these movements, in the years preceding and following the invention of Earth First!, there was enough overlap in the ideas and people involved in Bioregionalism and Earth First! that the main elements of what could be called the worldview of radical environmentalism came into view.

So, when Earth First! announced its arrival and intention to disrupt politics as usual, there was fertile countercultural ground upon which to draw. Indeed, in the early 1980s, there were many radicals without a cause, as the Cold War and nuclear anxieties had ebbed and Latin American revolutions were pacified, while environmental alarm, even apocalypticism, had continued to grow, fueled in part by the Club of Rome’s landmark 1972 report titled The Limits to Growth. The stage was set for the dramatic entry of Earth First! into US environmental politics.