3. Petra Kelly: Transnational Green Politics and Dark Green Spirituality

Petra Kelly was an outspoken opponent of the proliferation and use of nuclear technologies and a staunch advocate for the rights of women and minority populations. A close examination of Kelly’s transnational antinuclear activism and ecological perspectives illuminates the ways in which her work was informed and shaped by her spiritual perspectives.

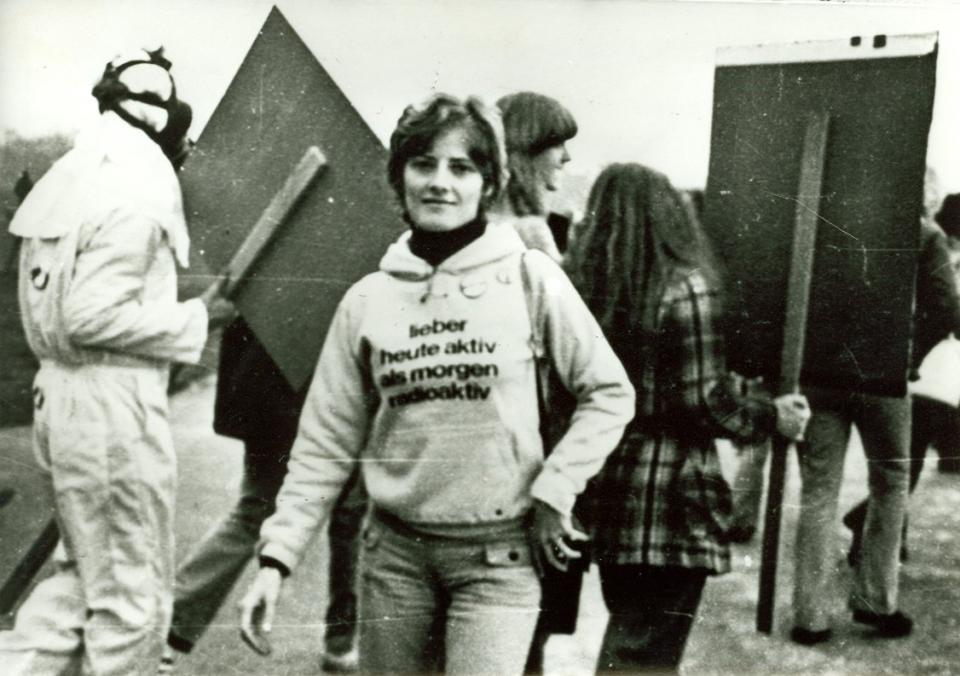

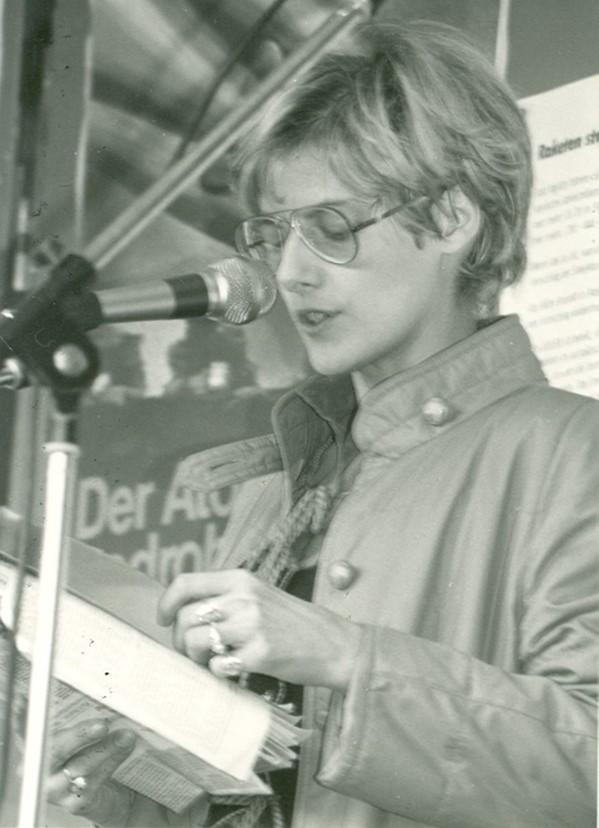

Figure 1. Petra Kelly at a demonstration against the planned construction of Ireland’s first nuclear power station, Carnsore Point, on 18 August 1978, wearing a sweatshirt that reads “Lieber heute aktiv als morgen radioaktiv” (Rather active today than radioactive tomorrow).

Figure 1. Petra Kelly at a demonstration against the planned construction of Ireland’s first nuclear power station, Carnsore Point, on 18 August 1978, wearing a sweatshirt that reads “Lieber heute aktiv als morgen radioaktiv” (Rather active today than radioactive tomorrow).

Unknown photographer, 1978. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-01558. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

As a child, Kelly was raised in the Catholic tradition and attended a Roman Catholic girl’s school, the Englisches Institut (English Institute), in Günzburg, Germany. In 1958, Kelly’s mother married Lieutenant Colonel John E. Kelly, and the family moved to the United States in 1959. It was there that Kelly was first introduced to feminism, civil rights, and critiques of hierarchical power structures in society. This early exposure to radical social perspectives proved formative for Kelly in that they contributed to the development of her worldview and later influenced her green political platform and activism. At American University in Washington, DC, she studied politics and international relations and became alert to political activism in the anti-war, civil rights, and feminist movements. There she also learned about the nonviolence traditions of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., which informed her later environmental politics.

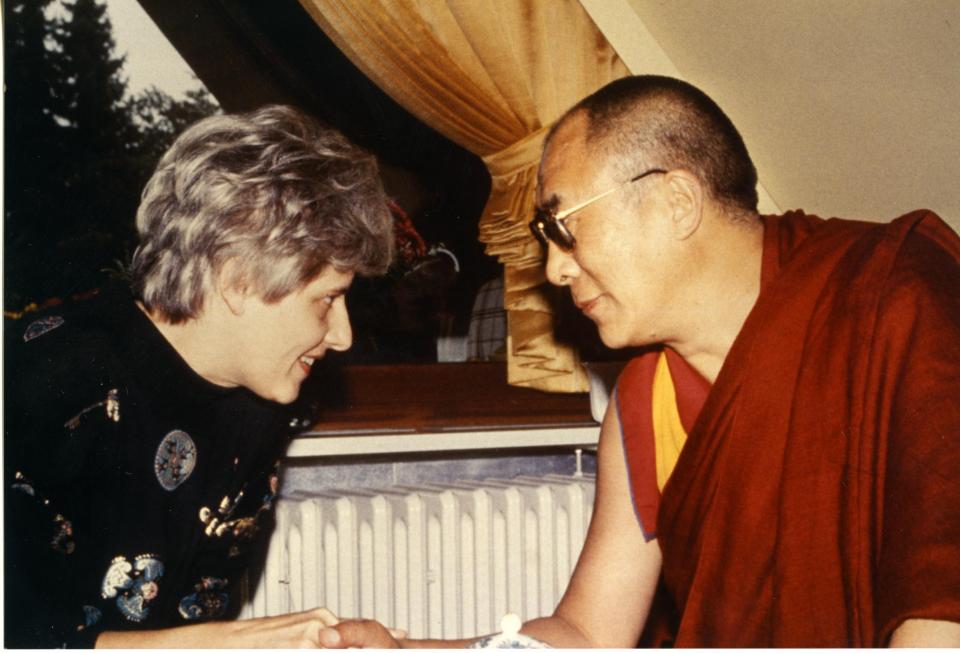

Though Kelly eventually rejected the Catholic Church, which she saw as an “authoritarian male institution,” her upbringing in the tradition was, at least in some ways, influential, and Kelly remained a spiritual person throughout her life. She was especially moved by Tibetan Buddhism and its focus on nonviolence and nonhierarchical leadership structures, though she did not ascribe to the tradition herself.

Figure 2. Petra Kelly with the Dalai Lama in Hamburg on 8 October 1991.

Figure 2. Petra Kelly with the Dalai Lama in Hamburg on 8 October 1991.

Unknown photographer, 1991. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-05595-01). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

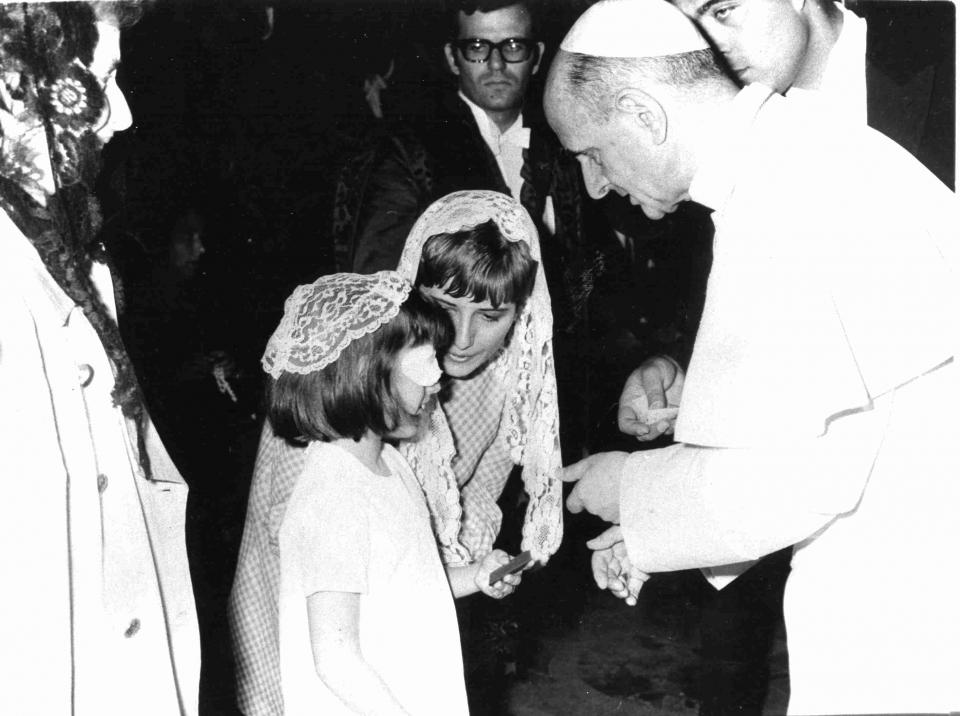

Kelly expanded her worldview through her work in transnational politics and antinuclear activism during the 1970s and 1980s. When Grace, her younger half sister, died from eye cancer in 1970, Kelly became aware of the impacts of ionizing radiation—which was used in her sister’s treatment—on human populations. In 1982, Kelly reflected on her sister’s death, calling it “the key point” in her life.

Figure 3. Petra Kelly pictured with her half sister, Grace, and Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in a meeting she arranged in the hopes that it would help with Grace’s battle with cancer, June 1968.

Figure 3. Petra Kelly pictured with her half sister, Grace, and Pope Paul VI at the Vatican in a meeting she arranged in the hopes that it would help with Grace’s battle with cancer, June 1968.

Unknown photographer, 1968. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Kelly channeled her grief into educating herself about nuclear technologies and the impacts of those technologies on human populations and the environment. She became active in a number of environmental organizations including the Bundesverband Bürgerinitiativen Umweltschutz (BBU, Federal Association of Environmental Action Groups) and was a founding member of Die Grünen in 1980. In 1983, Kelly was elected to serve as a representative of the Greens in the Bundestag (the German parliament). In the Bundestag, she also served on the Unterausschuss Abrüstung (Subcommittee of Disarmament) where she became internationally renowned for her outspoken antinuclear politics.

Kelly’s personal experiences coalesced with her knowledge about global, social, and political systems and with her religious perspectives. Combined, these perspectives informed the ecological worldview and vision for the future for which she fought adamantly as a green politician. An outspoken (eco)feminist, Kelly saw social disparity, inequity, and violence as the products of a patriarchal system that disproportionately impacted minority populations while destroying the planet and threatening global peace and social stability. To “rid the world of nuclear weapons and poverty,” Kelly wrote, “we must end racism and sexism.”

Kelly was erudite: in interviews and public appearances, she relied on scientific data and political acumen to communicate her vision for the future. She spoke avidly about her ecological vision of “restoring balance” by “living with the Earth,” eliminating nuclear technologies, and employing soft technologies, which she understood as “technology for people and for life.” In her 1982 two-part interview with Trevor Hyett, Kelly detailed her understanding of the inextricable connections between “ecology” and “global questions of survival, the threat of war, exploitation of raw materials, population growth, [and] misery for [hu]mankind.” “These things are all interrelated,” she insisted.

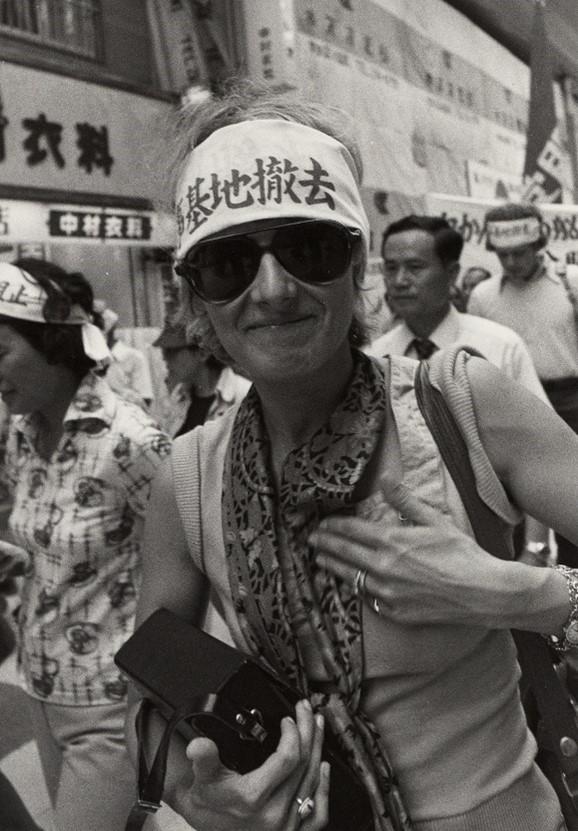

Her knowledge about the dangers of nuclear technologies and growing prominence in German politics furthered her engagement on the global antinuclear stage. She traveled around the world as an invited guest, speaker, and participant in numerous international antinuclear forums and peace demonstrations, including in Japan (1976), Australia (1977), Ireland (1978), London (1980), Moscow (1983 and 1987), Washington, DC (1983), France (1986), and Spain (1986), among many others.

Figure 4. Petra Kelly marches in a peace demonstration in Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1976.

Figure 4. Petra Kelly marches in a peace demonstration in Hiroshima, Japan, in August 1976.

Unknown photographer, 1976. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-01579-07). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Figure 5. Petra Kelly as a speaker at an event of the peace movement, November 1981: “Nuclear death threatens everyone.”

Figure 5. Petra Kelly as a speaker at an event of the peace movement, November 1981: “Nuclear death threatens everyone.”

Unknown photographer, 1981. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-03214-01). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

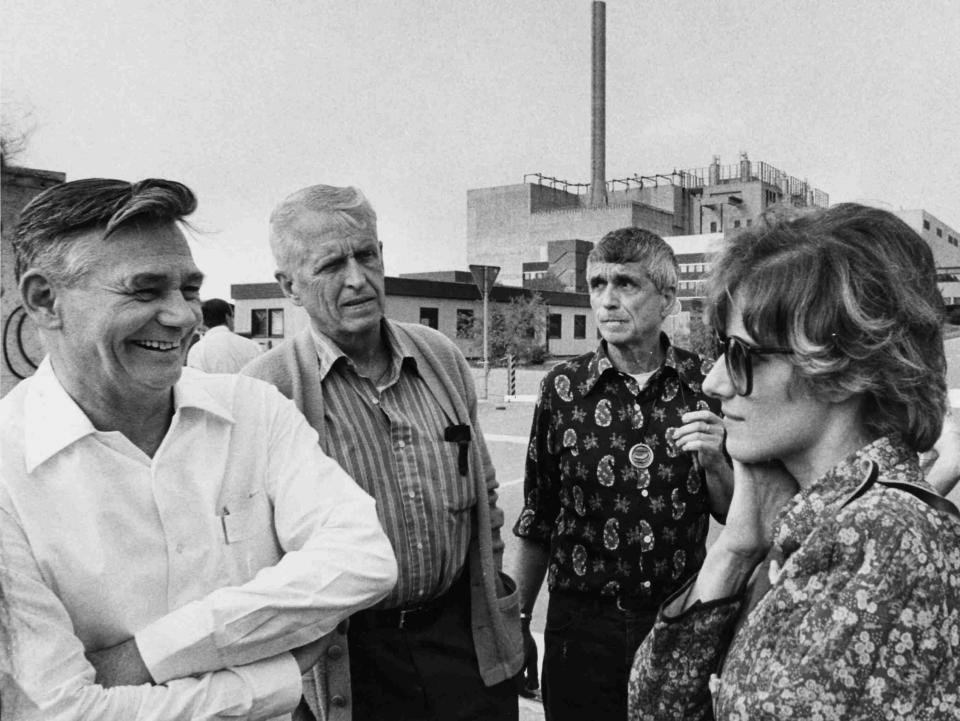

In this role, she met and engaged with numerous other antinuclear activists, including the famous activist priests Daniel and Phillip Berrigan, who were among the founders of the Christian pacifist Plowshares movement in the United States. Taking their name from the Biblical passage from Isaiah 2:3–4, which states “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more,” the Plowshares practiced nonviolent civil disobedience in protest against nuclear weapons.

Figure 6. Petra Kelly pictured with the Berrigan brothers in May 1982 at a blockade at the Schneller Brüter (fast breeder) reactor in Kalkar, Germany. Pictured: Phillip Berrigan (second from left), Daniel Berrigan (second from right), Petra Kelly (right).

Figure 6. Petra Kelly pictured with the Berrigan brothers in May 1982 at a blockade at the Schneller Brüter (fast breeder) reactor in Kalkar, Germany. Pictured: Phillip Berrigan (second from left), Daniel Berrigan (second from right), Petra Kelly (right).

Photo by Stefan Horn, 1982. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signature: FO-1346-01). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The important influence of this religious perspective on Kelly is evidenced through her own engagement with the Plowshares group, and her use of their motto in her own activism. In 1983, Kelly crossed the wall into East Berlin and, along with four other activists from Die Grünen, unfurled a banner bearing the “Swords into plowshares” motto in Alexanderplatz. This incident led to her arrest. In part, this was because the motto, which had been employed by East German Protestant peace activists, had been banned by the Communist authorities in East Germany in 1982.

Figure 7. Petra Kelly and other activists from the West German Die Grünen in Alexanderplatz on 12 May 1983.

Figure 7. Petra Kelly and other activists from the West German Die Grünen in Alexanderplatz on 12 May 1983.

Unknown photographer, 1983. © Archiv Grünes Gedächtnis (signatures: FO-01908-01-cp and FO-01908-03). Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Because of the important global networks she built, Kelly became instrumental in organizing transnational communications between governments and institutions aimed at facilitating peace around the world. These important connections supplied information that further enabled her to protest nonviolently by introducing important counterinformation—or, as Kelly defined it in Nonviolence Speaks to Power, information that introduces and “spotlights problems and conditions contrary to official interpretations”—into parliamentary discussions. Kelly’s activism and political work demonstrate her dramatic influence within the broad antinuclear, religious, political, and environmental milieux of her day.

Today we might understand Kelly’s views—her social, political, and environmental views—as an example of what Bron Taylor has called Gaian Naturalism. As Taylor described it, dark green religion is a form of “religion that considers nature to be sacred, imbued with intrinsic value, and worthy of reverent care.” It is “dark” due both to its “depth . . . of consideration for nature” and because of its potential to “precipitate or exacerbate violence.” This naturalistic spirituality played an important role in shaping Kelly’s understanding of the interrelated nature of political, social, and environmental systems. Moreover, it motivated her transnational political efforts to change (inter)national nuclear policies aimed at eliminating nuclear weapons and helping those disproportionately affected by nuclear technologies.

Kelly’s ecological thinking was grounded in a holistic understanding of the inextricable connections between social, political, and environmental systems. For her, “green politics . . . always had a spiritual base,” which meant “respecting all living things and knowing about the interrelatedness and interconnectedness of all living things.” Spiritual growth, she believed, was essential to addressing political problems, ending social disparity, and promoting peace. In her writing and speeches, Kelly often linked notions of spirituality to her activist and political commitments to people and the planet. She regularly engaged in civil disobedience and held that “nonviolence is a spiritual weapon” that can and should be used against “the existing system of dominance and privilege [to] give more conscious attention to the building of an alternative social structure.”

Today, as we look back and reflect on Kelly’s political work and activism, we might understand the depth of her concern as fueled in part by her own personal grief and by her knowledge of the catastrophic implications for both humans and the rest of the living world that would follow a global nuclear-weapons exchange. She did not demur from political activism and nonviolent resistance, and she was a fierce opponent of nuclear technologies precisely because she knew what was at stake. Kelly’s lifework exemplifies the role that spirituality plays in the lives of many activists, driving efforts to prevent disaster and inspire peace. Her work also underscores how spirituality, including the dark green form Kelly exemplifies, has become increasingly relevant in grassroots environmental activism and transnational environmental politics.