Moat–Bridge

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of maps. View the images on the following pages.

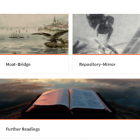

Map by Abraham Ortelius, c. 1570. Public domain.

Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 24 February 2021. Click here to view source.

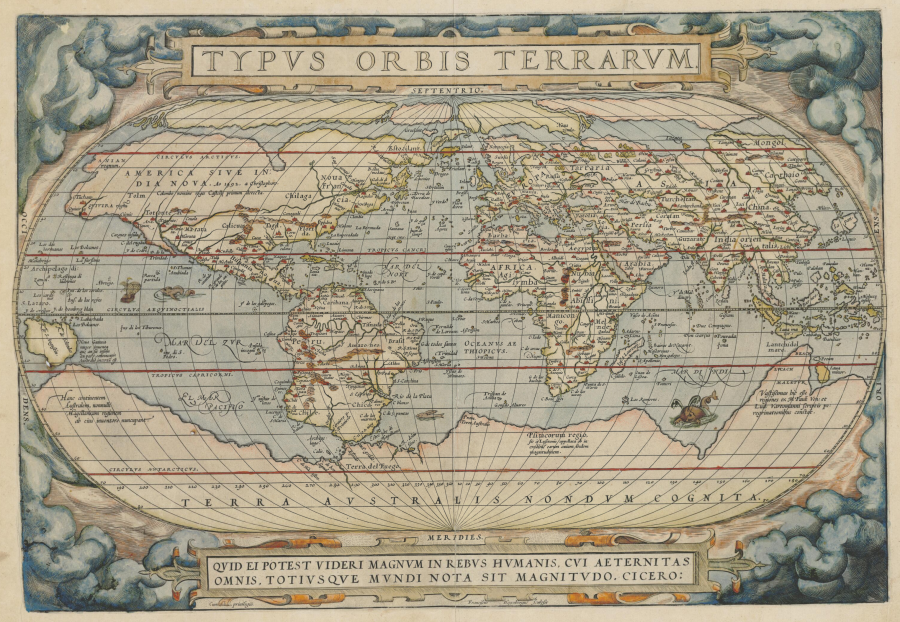

Map by Alfred Russel Wallace and J. Arrowsmith, 1863. Public domain.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 24 February 2021. Click here to view source.

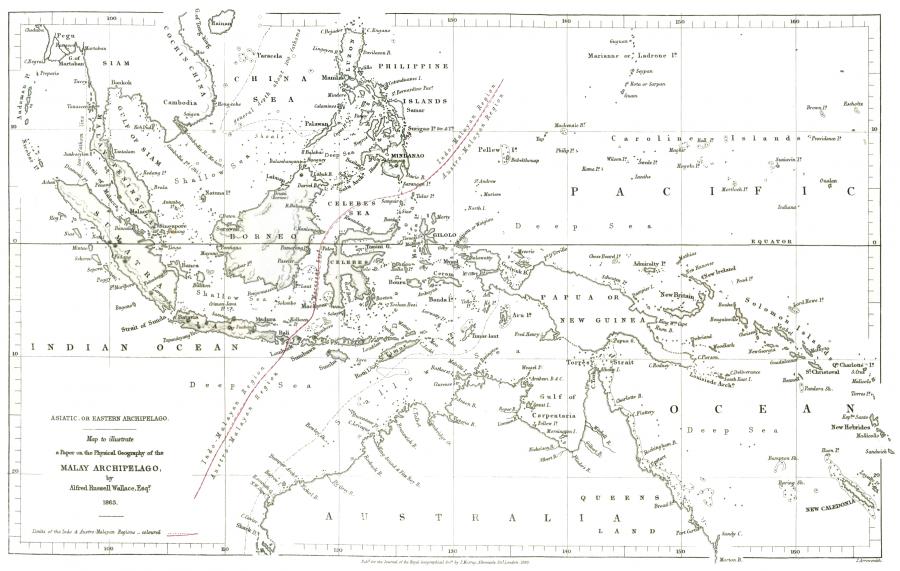

Map by Olaus Magnus, 1539. Public domain.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 24 February 2020. Click here to view source.

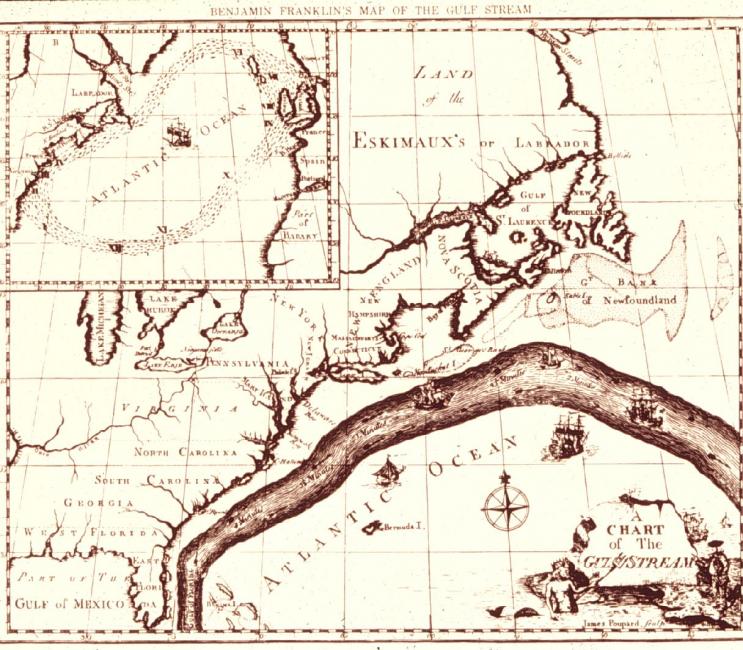

Map by Benjamin Franklin, c. 1782. Public domain.

Courtesy of NOAA Photo Library. Click here to view source.

Gravestone with a lateen-rigged sail and other maritime motifs in a twelfth- or thirteenth-century Muslim cemetery in Istanbul, Turkey. The rise and spread of Islam promoted sea trade through laws that benefitted trade, the use of the Arabic language as a lingua franca, and the knowledge and experience of Arab navigators. Photograph by Daniel Hornstein, 2016.

Gravestone with a lateen-rigged sail and other maritime motifs in a twelfth- or thirteenth-century Muslim cemetery in Istanbul, Turkey. The rise and spread of Islam promoted sea trade through laws that benefitted trade, the use of the Arabic language as a lingua franca, and the knowledge and experience of Arab navigators. Photograph by Daniel Hornstein, 2016.

Unknown sculptor, n.d.

© 2016 Daniel Hornstein.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Atlantic Ocean separated the Americas from Europe and Africa until the Columbian Exchange, when Europeans initiated an uneven biological exchange of people, plants, animals, and pathogens between the Old and New Worlds. The Atlantic crossings grew from an economic desire to reach the fabled riches of China, but the ocean was bridged as well by “islands of the mind.” Actual islands, as well as imagined ones such as St. Brendan’s Isle or Hy-Brasil, reassured mariners by dividing the frightening, open ocean into crossable segments. For English Puritans seeking religious freedom, the remoteness of their new home made American shores seem a sanctuary for God’s chosen people. The only way for immigrants, both voluntary and involuntary, to reach the Americas involved a long, often dangerous, and uncomfortable crossing by ship. This experience contributed to the United States’ sense of its national history as unique and separate from the Old World. American resistance to involvement in European affairs sustained the idea of ocean as moat, even as the nation expanded into the Caribbean and across the Pacific.

Maritime history traditionally touts the role of ocean as bridge. Seas provided linkages between groups of people, along a coast or around the globe, for trade, migration, or pursuit of resources. This function dates far back in time and continues in the present. Archaeologists now think the Americas were first settled by voyagers who moved easily in boats along the western, northern, and eastern coasts of the North Pacific. Following the “kelp highway,” they used resources from both land and sea, the latter provided by the rich kelp beds that formed a consistent environment with familiar and predictable resources. Chinese treasure fleets of the fifteenth century forged tributary relationships between the Emperor and communities as far away as East Africa. European explorers in the sixteenth century discovered sea routes between the earth’s known lands. They found the New World and the enormous Pacific Ocean as they searched for ways to reach Asia and its storied trade goods. Today, while people travel between terrestrial destinations by plane, almost 90 percent of every consumer product arrives by ship, making the global shipping industry as important as it is invisible.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive, animated map. Interactive by Andrew Kahn. Background image by Tim Jones. View the animated map online here.

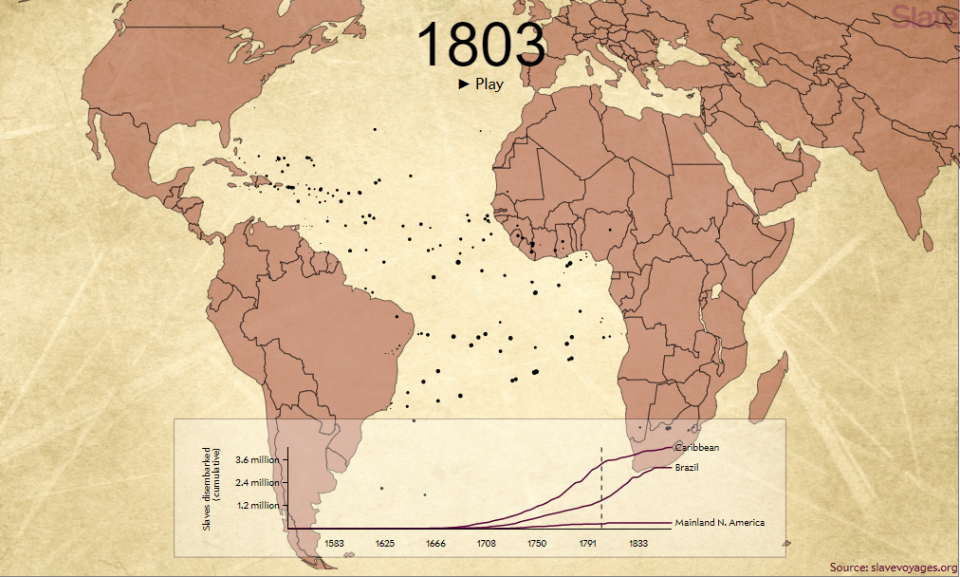

Interactive media, “The Atlantic Slave Trade in Two Minutes,” displays over 20,000 voyages from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries that brought over ten million enslaved Africans across oceans to the Caribbean, Brazil, and North America. Not only did the sea serve as a bridge to move these people against their will to other continents but it then served as moat preventing their return. Click the map to see the interactive version. Interactive by Andrew Kahn and background image by Tim Jones, 2015.

Interactive media, “The Atlantic Slave Trade in Two Minutes,” displays over 20,000 voyages from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries that brought over ten million enslaved Africans across oceans to the Caribbean, Brazil, and North America. Not only did the sea serve as a bridge to move these people against their will to other continents but it then served as moat preventing their return. Click the map to see the interactive version. Interactive by Andrew Kahn and background image by Tim Jones, 2015.

© 2015 Slate

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Allegorical scene celebrating the successful 1866 laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable, bridging Britain, represented by the lion, and the United States, represented by the eagle. King Neptune rests on the ocean floor as if welcoming and protecting the wires and the instantaneous communication between continents they enabled. Submarine telegraphy represents a rare instance when the ocean acting as bridge (or moat, in the years in which efforts to lay the cable were unsuccessful) involved the seafloor rather than its surface. Illustration by Kimmel & Forster, 1866.

Allegorical scene celebrating the successful 1866 laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable, bridging Britain, represented by the lion, and the United States, represented by the eagle. King Neptune rests on the ocean floor as if welcoming and protecting the wires and the instantaneous communication between continents they enabled. Submarine telegraphy represents a rare instance when the ocean acting as bridge (or moat, in the years in which efforts to lay the cable were unsuccessful) involved the seafloor rather than its surface. Illustration by Kimmel & Forster, 1866.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

After the Second World War, the American entrepreneur Malcolm McLean developed technology for transporting materiel during wartime into a system for moving cargo easily and quickly between land and sea by carrying it in standardized containers that could be transferred between trains, trucks, and ships. Containerization decreased the cost of shipping and kept it low but decimated employment for the stevedores who had previously loaded cargo piece by piece. Container ships, joined by other specialized vessels for transporting liquids, gasses, and bulk cargoes, enabled the transport over oceans of four hundred times more cargo in the early twenty-first century compared with the mid-nineteenth and helped create economic globalization, yet has rendered maritime laborers invisible and has transferred marine species around the world, altering coastal ecosystems in the process. Unknown photographer, 1957.

After the Second World War, the American entrepreneur Malcolm McLean developed technology for transporting materiel during wartime into a system for moving cargo easily and quickly between land and sea by carrying it in standardized containers that could be transferred between trains, trucks, and ships. Containerization decreased the cost of shipping and kept it low but decimated employment for the stevedores who had previously loaded cargo piece by piece. Container ships, joined by other specialized vessels for transporting liquids, gasses, and bulk cargoes, enabled the transport over oceans of four hundred times more cargo in the early twenty-first century compared with the mid-nineteenth and helped create economic globalization, yet has rendered maritime laborers invisible and has transferred marine species around the world, altering coastal ecosystems in the process. Unknown photographer, 1957.

Courtesy of Mærsk A/S. The image has been cropped.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 5 April 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.