Destination–Home

View of the Earth seen and photographed by the Apollo 17 crew on 7 December 1972 as they traveled toward the moon. Dubbed the “Blue Marble,” this image impressed viewers with the Earth’s contrast to black, lifeless space and prompted reflections on the finite nature of the globe’s resources. It also provided a glimmer of public recognition of the importance of the oceans for life on earth. Photograph by NASA, 7 December 1972.

View of the Earth seen and photographed by the Apollo 17 crew on 7 December 1972 as they traveled toward the moon. Dubbed the “Blue Marble,” this image impressed viewers with the Earth’s contrast to black, lifeless space and prompted reflections on the finite nature of the globe’s resources. It also provided a glimmer of public recognition of the importance of the oceans for life on earth. Photograph by NASA, 7 December 1972.

Courtesy of NASA.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Before European contact Africans from the Gulf of Guinea coast and southward to South Africa possessed water-spirit traditions of mostly female figures. This twentieth-century wooden statue from Ghana portrays Mama Wati, the water spirit carried by enslaved Africans to the Caribbean and celebrated across much of the African Atlantic. The snake in her grasp represents her power to control snakes, while her woman’s torso and fish tail reflect her dual nature of good and evil, of earth and water, and of nature and culture. Unknown artist, 1900s.

Before European contact Africans from the Gulf of Guinea coast and southward to South Africa possessed water-spirit traditions of mostly female figures. This twentieth-century wooden statue from Ghana portrays Mama Wati, the water spirit carried by enslaved Africans to the Caribbean and celebrated across much of the African Atlantic. The snake in her grasp represents her power to control snakes, while her woman’s torso and fish tail reflect her dual nature of good and evil, of earth and water, and of nature and culture. Unknown artist, 1900s.

Gift of Kenneth and Bonnie Brown to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Object number 2015.414.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

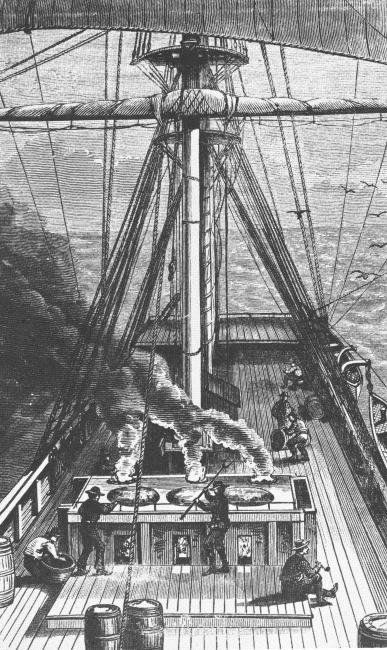

For most of history, the ocean has been a place for people to visit, either for resource use or to travel across en route from one land or island to another. The open ocean has not itself been a destination, as far as we know, for most of human history. It is for European eels seeking their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea or for young salmon heading to the open ocean to grow to maturity. Whalers may have been the first people to dwell on the high seas. Basques, who began commercial whaling by the eleventh century, left the Bay of Biscay for the North Atlantic by the sixteenth century as their quarry grew scarce near the coast. By the early nineteenth century, whalers installed tryworks to render whale blubber on board their ships. Freed from ties to land, they spent years hunting their prey at sea. Whaling contributed to the mid-century discovery of the deep ocean. This simultaneous scientific and cultural discovery involved submarine telegraph engineers, naval hydrographers, middle-class marine naturalists, and yachtsmen and women, as well as readers, aquarium keepers, and beachgoers. Together these interests in the deep sea helped redefine the ocean. Today’s ocean is destination as well as highway: for spearfishers or underwater photographers a site of recreation; for cruise ship passengers a site of pleasure; for circumnavigators a personal challenge; and for some merchant mariners an enforced home, when they are not permitted ashore during brief stops of their gigantic tankers or cargo ships at industrial ports.

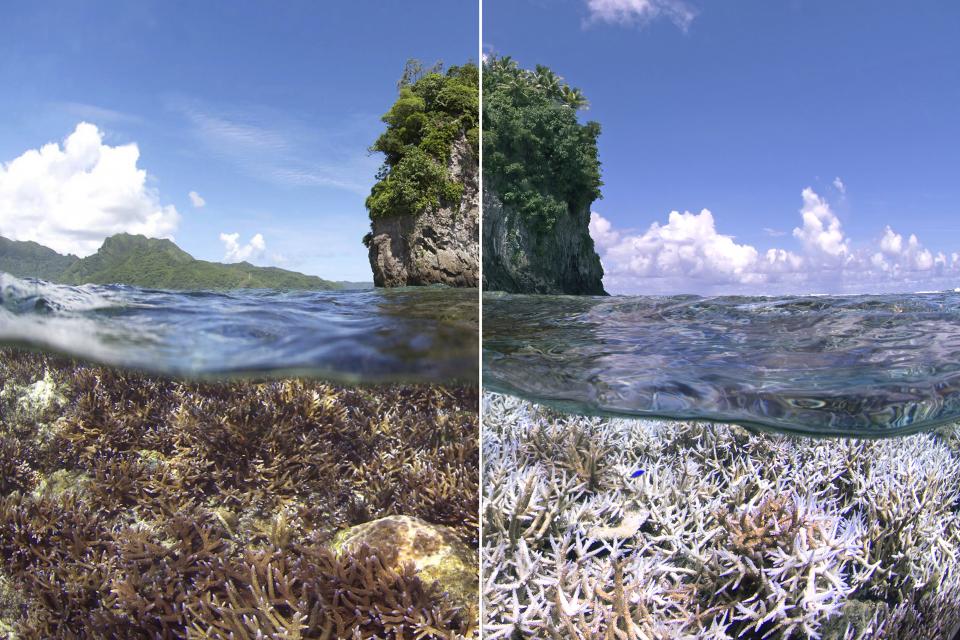

On the right is a healthy reef in American Samoa in December of 2014. In February 2015, during a bleaching event, the same reef is shown on the photograph on the left. Warmer than usual water temperatures can cause bleaching; the white color results from the coral expelling its symbiotic algae in response to the temperature shift, leaving the coral stressed and the reef covered with slime. This image comes from the Coral Reef Image Bank, a resource created in recognition of the importance of visual imagery in inspiring conservation and climate action. Scientists predict that if humans disappeared from Earth, reefs and most marine species would recover, reminding us that we need the ocean more than it needs us. Photograph by the Ocean Agency, n.d.

On the right is a healthy reef in American Samoa in December of 2014. In February 2015, during a bleaching event, the same reef is shown on the photograph on the left. Warmer than usual water temperatures can cause bleaching; the white color results from the coral expelling its symbiotic algae in response to the temperature shift, leaving the coral stressed and the reef covered with slime. This image comes from the Coral Reef Image Bank, a resource created in recognition of the importance of visual imagery in inspiring conservation and climate action. Scientists predict that if humans disappeared from Earth, reefs and most marine species would recover, reminding us that we need the ocean more than it needs us. Photograph by the Ocean Agency, n.d.

© Ocean Agency.

Click here to view source.

Free to use.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Like all shipwrecks, this one from the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, demonstrates how the ocean is not home to people and their technology. The sunken USS Arizona is the resting place of 1,102 sailors and Marines killed on board. The colorful underwater life on this hull reminds us that shipwrecks become habitats for marine life, in this case even despite the slow leaking of oil from the wrecks at Pearl Harbor over the years. Photograph by Jill DeVito, 2014.

Like all shipwrecks, this one from the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, demonstrates how the ocean is not home to people and their technology. The sunken USS Arizona is the resting place of 1,102 sailors and Marines killed on board. The colorful underwater life on this hull reminds us that shipwrecks become habitats for marine life, in this case even despite the slow leaking of oil from the wrecks at Pearl Harbor over the years. Photograph by Jill DeVito, 2014.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 5 March 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The ocean is not generally viewed as a home for people, as shipwrecks ancient and contemporary attest. Yet many cultures have explored the limits of life undersea. Groups of people in the Philippine Islands, Indonesia, Thailand, and China live on boats, depend on marine resources, and in some cases appear to have physical adaptations for breath-hold diving. Post–World War II dreams of technology enabling people to work and live underwater have not materialized. Instead, the recent increase in shark attacks reminds us that humans underwater trespass in an environment that is home for nonhuman species. We increasingly understand the scale and extent of overfishing, plastic pollution, and myriad other harms done to the marine environment by human activities. Similarly, we grow more aware of the unequal effects of this damage as a postcolonial legacy. Our actions as a species endanger home for many sea creatures but, ironically, also threaten the planetary-scale home that people share with all other forms of life. Ecologists believe that, without us, reefs and other oceanic places would recover—a reminder that we need the oceans more than they need us.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of images. Please view the images on the following pages.

Willy Stöwer, Deutsches U-Boot, einen bewaffneten englischen fischdampfer vernichtend, 1916. Public domain.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Click here to view source.

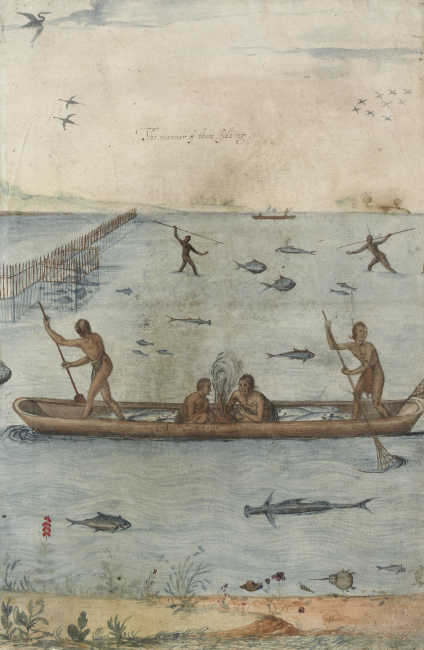

John White, The Manner of Their Fishing, 1585–1593. Public domain.

Courtesy of the British Museum. Click here to view source

Henry de la Beche, Duria antiquior, 1830. Public domain.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 21 April 2021. Click here to view source

Unknown engraver, n.d. Public domain.

Published in William M. Davis, Nimrod of the Sea; or, The American Whaleman (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874).

Engraving by A. Y. B., n.d. Public domain.

Published in Anne Brassey, A Voyage in the “Sunbeam”: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months (London: Spottiswood and Co., 1878: 423).

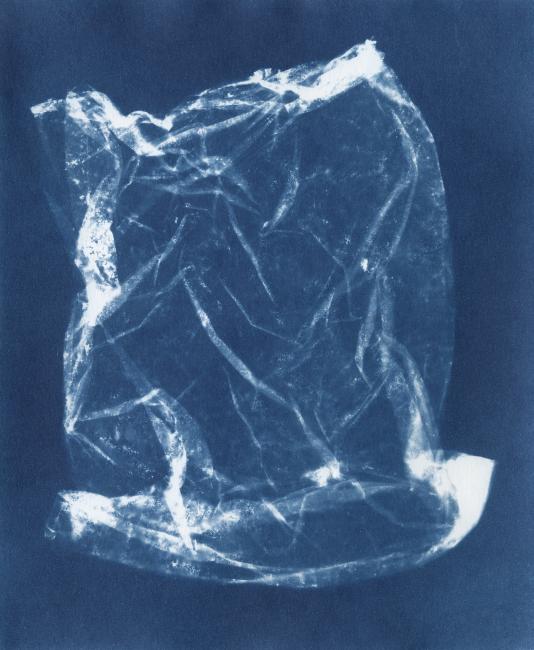

Photograph by Elizabeth Ellenwood, 2019.

http://elizabethellenwood.com.

Used by permission.

The No Word for Worry film trailer introduces indigenous sea nomads who call themselves the Moken, or sea people. Living along the west coast of Burma and Thailand in the Mergui archipelago, the Moken face threats to their traditional way of life, which has involved living mostly on boats and deriving subsistence from the sea. Those threats come from overfishing by industrial fisheries and political persecution by governments that try to force them to settle permanently on land. In the trailer, Hook Suriyan Katale relates his peoples’ plight and is filmed diving, demonstrating his impressive breath-holding and underwater swimming abilities. In 2004 some groups of Moken anticipated the tsunami and moved to high ground for safety, revealing the depths of their knowledge of oceanic phenomena.

Whale falls, like the one discovered by the 2019 Nautilus Expedition lying at over 3000 meters near the Davidson Seamount in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, are carcasses of dead whales that sink to the deep ocean floor to become a bonanza-style food source for many kinds of marine creatures. First come scavengers such as hagfish or octopuses and then deep-sea specialized crabs, isopods, sharks, prawns, bacteria, microbes, and other fauna whose life cycles take advantage of the nutrients and fats provided in this otherwise challenging environment. In 2002 scientists discovered whale falls to be home to a previously unknown genus named Osedax, more commonly called bone-eating worms or zombie worms, and more recently they are beginning to recognize whale falls as significant for global carbon sequestration. Video by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The original virtual exhibition features the film trailer No Word for Worry (2012). 3 min 25. View the film online here.

The original virtual exhibition features the film Whale Fall in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (2019). 2 min 25. View the film online here.