Forests and Deforestation

The Forest as Border

Endangered Virgin Forests

The Forest Beyond Humanity

Sustainable Living in the Forest

Forests as Discourse

Related Links

Literary engagement with forests and deforestation is particularly central in Austrian literature.

The German forester Hans Carl von Carlowitz, in his 1713 Silvicultura oeconomica, was the first to discuss forests as resources for wood in the context of sustainability. Carlowitz conceived of a sustainable practice for harvesting forests so that future generations would not be adversely impacted, and so that they would have access to the same resources as the current generation.

Forests later became important subjects in German romantic poetry: not from a perspective that viewed them as a resource, but as locations for mythical concepts about nature, and the role of humans in nature, to be explored. Romantic youths wander through these mythical forests singing romantic songs; others ride on horses or in postal carriages on the newly built and extended road system; others again make their living in the forest and use it as a buffer zone that allows them to practice their eccentric lifestyles.

Authors of romantic fairytales can therefore draw on a rich narrative tradition of forests, which is prevalent in the European fairytale tradition. The Brothers Grimm’s collection of fairy tales is but one source in which the woods are full of potential dangers (witches, outlaws, and wild animals make their homes in them) but also in which characters can find refuge and shelter from vicious parents and stepparents.

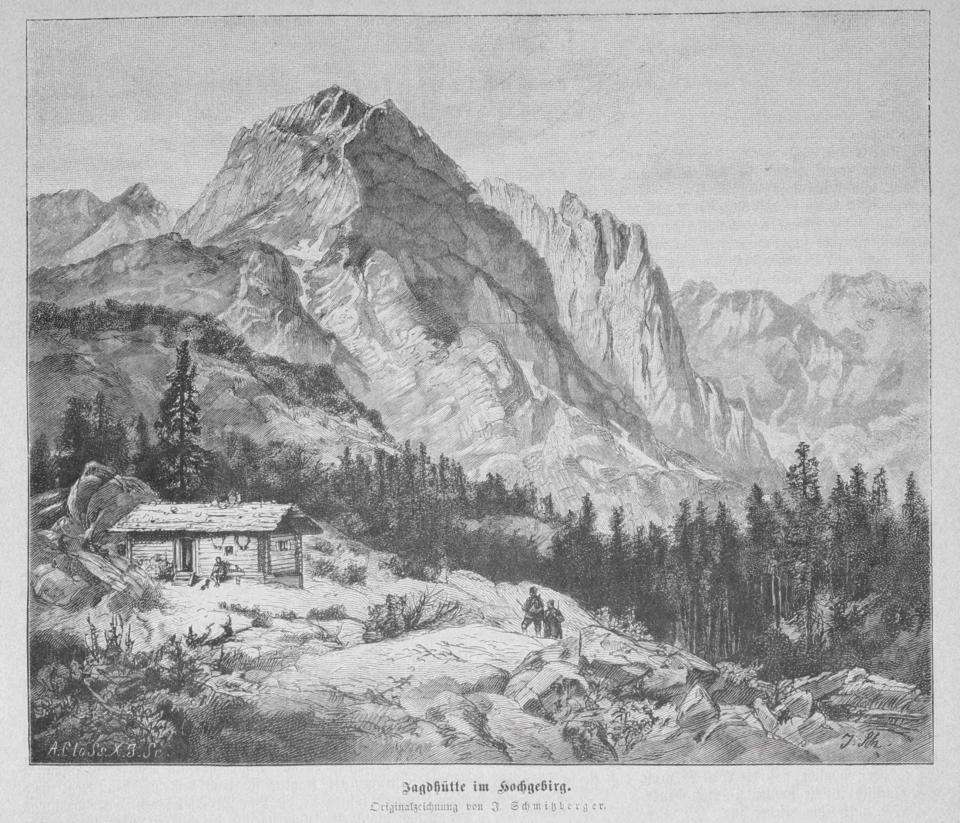

Drawing of a hunting cabin in the journal Gartenlaube. Joseph Schmittzberger, Jagdhütte im Hochgebirge, 1888.

Drawing of a hunting cabin in the journal Gartenlaube. Joseph Schmittzberger, Jagdhütte im Hochgebirge, 1888.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In contemporary literature, Austrian writers have focused intensely on narrating forests and have recently even begun to include the topic of deforestation in their work. The forest is thus often framed in the context of its own disappearance.

A prominent Austrian prose writer and painter of the nineteenth century, Adalbert Stifter, created literary figures that knew the old stories about the woods as places of refuge from civilization, or for eccentricities. But his characters also realize that the forests are retreating, and that even the most dense forests can no longer be considered safe havens from encroaching civilization, or places that can provide shelter from danger. The modern forest is more and more prone to human influence, be that from extensive deforestation, or from an ever-expanding tourist infrastructure. Most recently, environmental hazards that trigger the death of the forest and cause environmental depredation have become popular literary topics.

In the novel Die Wand (The Wall) set in the sixties, the postwar Austrian writer Marlen Haushofer situates her female protagonist quite literally behind a mysterious wall. Here, she finds herself alone in a picturesque portion of the Austrian Alps, the only human being around. She has to learn how to manage her allotted portion of the woods sustainably and care for her animals, which becomes a long and tedious process that leads to only partial success. Most importantly, the ending of this experiment remains unresolved.

Nobel Prize laureate Elfriede Jelinek’s Austrian forests, however, are severely impacted by human activity, whether by expansive industrial logging or a dense system of tourist trails and roads. Loggers demand their right to work, and to harvest the forest as a resource for human development. Tourists demand access to trail systems for recreational purposes. Ski lifts are built everywhere, and forests give way to downhill ski slopes. Hikers, mountain bikers, and skiers crisscross through the last remaining continuous stretches of woods, and cars are able to fill up their tanks in remote gas stations and rest stops where there used to be nothing but forest.

The exploitative attitude of the loggers towards nature translates directly into their abusive attitudes towards women and family. The society of forest workers in Jelinek’s play Der Wald (The Forest) has reached a point where it is simply destructive. Jelinek shapes this situation poetically by using nothing but found language and common phrases about the forest in her collage, a technique that she employs to create the effect of the forest spitting back all these clichés to the readers of the play (and to the audience in the theater).

Literature shapes both the forest and the process of deforestation poetically, by highlighting human attitudes toward nature in this process. Readers and audiences are able to form critical opinions about these issues by weighing the characters’ perspectives against one another. Through these comparative techniques, literature contributes to the current discussion about environmental issues by promoting a more reflective and reflexive attitude toward forests and the processes of deforestation, which are accelerating at an alarming rate in our globalized world.

The Forest as Border

The Austrian nineteenth-century writer Adalbert Stifter’s tale on the fate of the pitch burners, later renamed “Limestone” (first published in 1849 as “The Pitch Burners”), eventually became part of the collection of stories entitled Bunte Steine (Colorful stones) in 1853. In the story, a grandfather takes his grandson for a walk through a regional forest, after a tar salesman paints the boy’s feet with oil and his mother gets angry with him for leaving oil stains on the floor of their house.

A block of granite. Photograph by Michiel Verbeek.

A block of granite. Photograph by Michiel Verbeek.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In the beginning of the story, the grandson is sitting on a granite block right outside of his house and is enjoying an excellent view of the surroundings, albeit noticing the first encroachments of human settlements on the otherwise idyllic rural agricultural landscape:

In front of the house in which my father was born, right next to the front door, there is a large octagonal rock that has the shape of a very long stretched-out die… . One of the younger members of our family that used to sit on this rock was myself during my childhood. I liked to sit on the rock since at least at that time one had a great view of the surroundings. Now it is completely obstructed by buildings.

—Adalbert Stifter, “Granit,” (1849), in Bunte Steine (München: Goldmann 1971), online at Projekt Gutenberg.

The Kürnberg Forest near Linz. Photograph by Christian Wirth.

The Kürnberg Forest near Linz. Photograph by Christian Wirth.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

I was looking at the ploughed fields that did not yet have any buildings on them. Sometimes I saw a piece of glass that shimmered like a white igneous spark and that glowed, or I saw a vulture fly by, or I saw the far bluish forest that reached up to the sky with its pointed teeth where the storms and torrential rains come down and that reaches so high into the air that I thought that it was possible to touch the sky when one climbed the tallest tree.

—Stifter, “Granit.”

Grazing moorland sheep (Heidschnucke). Photograph by Willow.

Grazing moorland sheep (Heidschnucke). Photograph by Willow.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

On other days I saw sometimes a harvest carriage, sometimes a herd, sometimes a beggar walking on the road that passed close to the house.

—Stifter, “Granit.”

The forest becomes a buffer zone between nature and those areas that are increasingly influenced and shaped by humans: mainly agricultural lands, but also human settlements. In the later nineteenth century, forests are increasingly framed through the perspective of loss and retreat.

Endangered Virgin Forests

Aside from the literary treatment of forests as buffer zones to human encroachment, Adalbert Stifter was also intensely interested in the concept of virgin forests and their disappearance. The grandfather in Stifter’s story “Limestone” tells his grandson about the forests near his home, which used to be much larger. To illustrate the vastness and significance of these larger virgin forests, the grandfather tells him a story about the pitch burners who used to live in and of the woods:

“If the evening sun wasn’t shining so bright,” grandfather said, “and everything was floating in a fiery smoke, I would be able to show you the location about which I am going to tell you and that fits into our narrative. It is several hours by foot, just across from us where the sun sets, and there are located the right woods. There firs and spruces, alders and maples, beeches and other trees stand tall like kings, and the population of bushes and the thick crowds of grasses and herbs, flowers, berries, and moss are among them.”

—Stifter, “Granit.”

Typical Central European mixed forest of pine, fur, and beech. Photograph by Nasenbär.

Typical Central European mixed forest of pine, fur, and beech. Photograph by Nasenbär.

Accessed on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In the grandfather’s story, the pitch burners retreated into these “right forests” mainly to escape the growing threat of infection from the plague.

“This pitch burner,” he continued, “wanted to avoid the general infestation that God imposed on humankind during the plague. He wanted to walk up to the deepest woods, where no one ever visits, where no air contaminated by people ever flows, where everything is different from below, and where he thought he could stay healthy… . But he went on further than where the lake is; he went all the way to where the woods are still in the state in which they were after creation, where people had never worked in them, where trees never break as if they were hit by lightning or knocked down by wind; then the fallen tree is left lying down, and new trees and herbs are growing from its body; the trunks are standing tall, and between them are the flowers and grasses and herbs that have never been seen and touched.”

—Stifter, “Granit.”

Map of the world’s intact forest landscapes. Graphic by Peter Potapov.

Map of the world’s intact forest landscapes. Graphic by Peter Potapov.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Similarly to the characters wandering through the woods singing in romantic poetry, Stifter’s grandfather still tries to read the book of nature as a system of allegorical signs, a system that is already showing the first signs of destruction and loss of traditional knowledge. The pitch burners are part of this culture of destruction and loss that no longer relates to the forest sustainably, but that prefigures the modern growing dependence on coal, gas, and oil in an accelerated process of modernization that is driven by the impending Industrial Revolution.

The Forest Beyond Humanity

A novel by the postwar Austrian writer Marlen Haushofer—The Wall (1963)—tells the story of a woman who accompanies a couple of friends to a hunting cabin located in a picturesque Alpine valley, near Salzburg. The woman suddenly finds herself trapped behind a mysterious wall, the only human survivor of an inexplicable environmental disaster that must have occurred on the other side of the wall.

With a hunting dog, a cat, and a pregnant cow, the female narrator is stuck in a relatively large but ultimately confined area of Alpine nature, and has to learn how to survive in this context. All the problems that she had in her urban existence are irrelevant as she needs to concentrate completely on surviving.

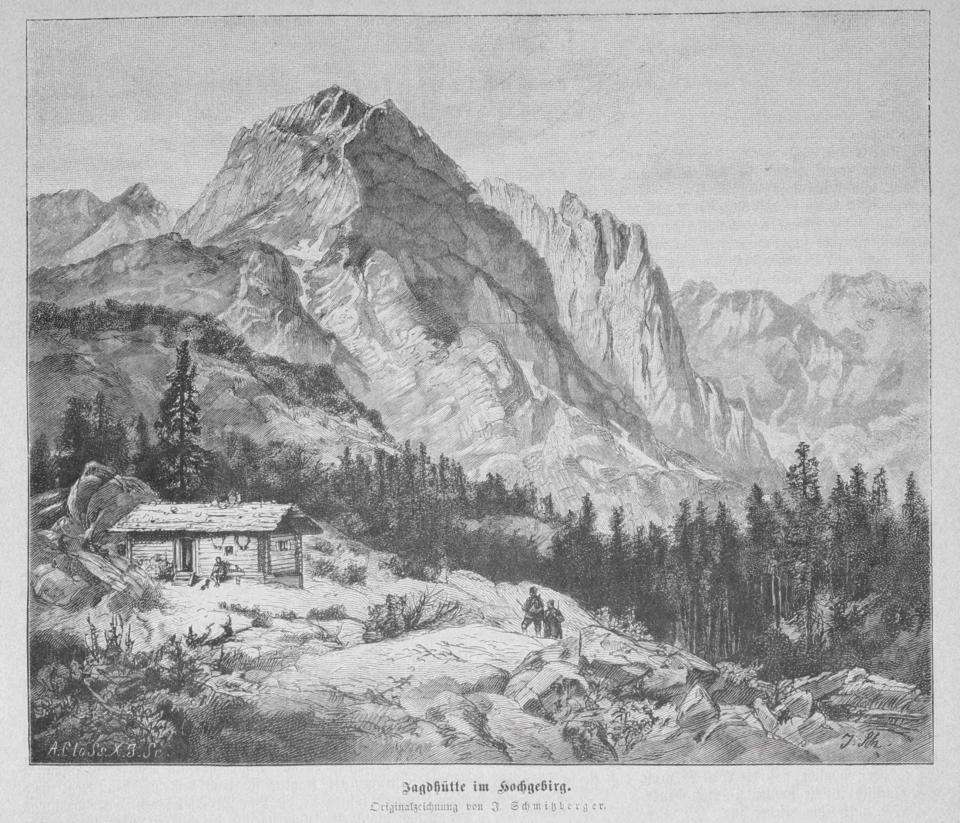

Drawing of a hunting cabin in the journal Gartenlaube. Joseph Schmittzberger, Jagdhütte im Hochgebirge, 1888.

Drawing of a hunting cabin in the journal Gartenlaube. Joseph Schmittzberger, Jagdhütte im Hochgebirge, 1888.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The challenge is to develop a lifestyle that is sustainable, one that guarantees the survival of her and her animals.

A blooming alpine rose (Rhododendron ferrogineum). Photograph by Muriel Bendel.

A blooming alpine rose (Rhododendron ferrogineum). Photograph by Muriel Bendel.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

At about one o’clock in the afternoon I reached the path through the mountain pines, and sat down on a stone to rest. The forest lay hazily in the midday sun, and the warm scent from the pines floated up to me. Only now could I see that the alpine roses were in bloom.

—Marlen Haushofer, The Wall (1963), trans. Shaun Whiteside, (San Francisco: Cleis, 1990), 50–51.

They stretched in a red ribbon over the scree. It was now much quieter than in the moonlight at night, as if the forest lay paralyzed by sleep beneath the yellow sun. A bird of prey circled high in the blue sky, Lynx slept, his ears twitching, and the great silence descended on me like a bell-jar. I wished I could sit here for ever, in the warmth, in the light; the dog at my feet and the circling bird above.

—Haushofer, The Wall.

A Eurasian griffon vulture. Photograph by Luc Viatour.

A Eurasian griffon vulture. Photograph by Luc Viatour.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source. Photographer’s website: https://Lucnix.be.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

I had stopped thinking long since, as if my worries and memories no longer had anything to do with me. When I walked on I did so with deep regret, and on the way I slowly changed, becoming the only creature that didn’t belong here, a person troubled by chaotic thoughts, cracking branches with her clumsy shoes and engaged in the bloody business of hunting.

—Haushofer, The Wall.

Fleeing roe deer. Photograph by Teytaud.

Fleeing roe deer. Photograph by Teytaud.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The human being is a disturbing factor in these Alpine woods, and as the text implies, it might be better for the forest if humans stayed away from it permanently. The author seems to suggest in her tale that only when humans are gone can there be true peace: a position not unlike that of some of the more radical strands of modern environmentalist thought.

Sustainable Living in the Forest

Marlen Haushofer’s novel The Wall (1963) continues with the female narrator’s self-reflexive commentary on the difficulties of becoming a human being who lives sustainably in her natural surroundings, when she herself was trained to simply take what she wanted in a modern consumer society that preached comfort and a surplus of resources.

In fact, I enjoy living in the forest now, and I’ll find it very difficult to leave it. But I shall come back, if I stay alive over on the other side of the wall. Sometimes I imagine how nice it would have been to bring up my children here in the forest. I think that would have been paradise for me.

—Haushofer, The Wall.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Paradies, 1530. Oil on lime, 81 x 114 cm. Held by Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Paradies, 1530. Oil on lime, 81 x 114 cm. Held by Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

But I doubt whether my children would have liked it that much. No, it wouldn’t have been paradise. I don’t believe that paradise ever existed. A paradise could exist only outside nature, and I can’t imagine that kind of paradise. It bores me even to think about it: I have no desire for it

—Haushofer, The Wall, 64–65.

This process of wrestling with a different attitude towards nature, one that is not based on conquest and the extraction of resources, is addressed thematically in the novel. However, it is not presented as a success story. The text simply ends when the protagonist runs out of paper, after four months of writing down her report of life behind the wall. There is no literary description of the forest and her life in it after that point in her adventure.

Today, the twenty-fifth of February, I shall end my report. There isn’t a single sheet of paper left. It’s now around five o’clock in the evening, and already so light that I can write without the lamp. The crows have risen, and circle screeching over the forest. When they are out of sight I shall go to the clearing and feed the white crow. It will already be waiting for me.

—Haushofer, The Wall, 244.

Traces of a crow in snow. Photograph by Ramessos.

Traces of a crow in snow. Photograph by Ramessos.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In this story, Haushofer radicalizes Stifter’s project of giving the forest a greater thematic presence by addressing the topic of sustainability from the forest’s perspective. A sustainable relationship between humans and forests, according to the narrative, would be based on a perspective towards human-nature entanglements that emphasizes the essential connection between the two. Humans must refrain from considering themselves as conquerors of the forest who exercise dominion over the plants and animals that grow in it.

Forests as Discourse

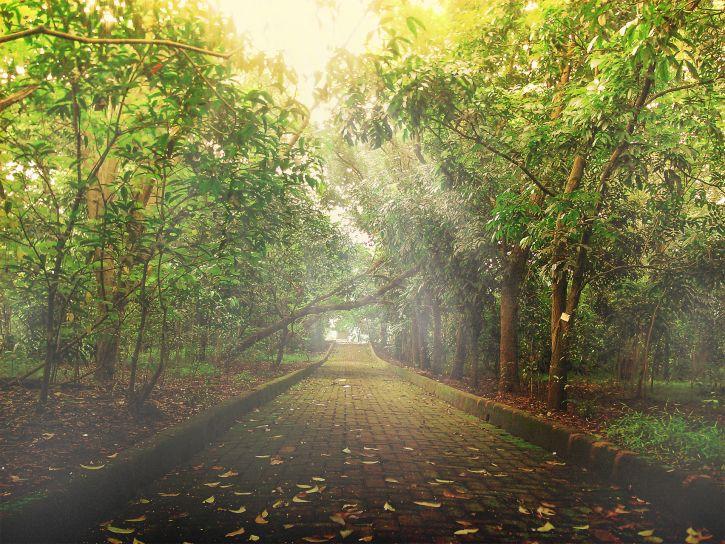

An urban forest in Jakarta, Indonesia. Photograph by Yogas Design.

An urban forest in Jakarta, Indonesia. Photograph by Yogas Design.

Accessed via PIXNIO on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In Nobel Prize laureate Elfriede Jelinek’s 1985 play Der Wald (The forest), the forest itself is no longer present, neither as actor or narrator—as in the work of Stifter and Haushofer—nor as a setting for the play. Jelinek’s forest only consists of words and discourse: it is a collage of common phrases describing the Austrian woods. Jelinek’s montage technique draws attention to the political and cultural meaning of forests, especially in the context of contemporary Austria and its sustained efforts to destroy the last remnants of forests.

Only three percent of Styria is covered with forests. Wouldn’t we go into the forests if we were able to? … We are ordered to form families, blind embryos. Exercise, ok, that is even meant for you, even if you are made out of plastic! Let’s go and insult the ground with cross-country skiing!

—Elfriede Jelinek, Der Wald, manuskripte 89/90 (1985): 43–44, esp. 44.

Cross-country skiers near Einsiedel. Photograph by Markus Bernet.

Cross-country skiers near Einsiedel. Photograph by Markus Bernet.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

Why not, we are not hurting anyone, we are the cause of destruction ourselves. The forest, even more beautiful than I thought, wow! They capture even your sleep in small-budget video films.

Newly cut road through the northern Bohemian Forest. Photograph by ŠJů.

Newly cut road through the northern Bohemian Forest. Photograph by ŠJů.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 September 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The forest is that which is beautiful, i.e., sublime gas stations during a modern car ride through the forest, on a highway that leads through it, by the way; a description of the highway is not necessary.

—Jelinek, Der Wald.

Jelinek’s post-natural forest, which consists of nothing but discourse, is exclusively the product of human activity. It no longer has any value of its own beyond the empty phrases that make up the content of the play. Even the loggers that engage with the forest have a solely practical attitude towards it, an attitude that is mirrored in their abusive family relationships:

They are lurking behind their ideal bonnet for a “family,” that’s how they hide themselves these birth defects and wage earners. They better shelter the forest from themselves. But they are covering the company towns and self-built family homes of the timber workers with their toxic veils.

Where the timber workers are dissecting their women into individual components in order to check whether or not improvements can be made by repairs.

—Jelinek, Der Wald, 43.

Workers’ housing complexes in Marienthal near Gramatneusiedl/Niederösterreich. Photograph by Joadl.

Workers’ housing complexes in Marienthal near Gramatneusiedl/Niederösterreich. Photograph by Joadl.

Photograph by Joadl. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The speakers in Jelinek’s play are preoccupied with money and social capital, an attitude that has completely replaced any genuine concern for the forests. The only perspective that counts is economic gain and short-term profit. These people have completely sold out to corporate interests and the tourism industry. Sustainable attitudes towards the forests are absent.

Related Links

Wikipedia article on the film Die Wand (The Wall)

Wikipedia article on Haushofer’s novel Die Wand (The Wall)