Fish Consumption

Both capitals were major centers of consumption in Europe. The growing population required a lot of food and fish was part of the city dwellers’ diets. Vienna and St. Petersburg used both local and imported food resources and often created specific recipes that determined local consumption culture. Significant social stratification led to the clear division between fish commodities for the wealthy and those for poor citizens, though some kinds of fish could be popular among all dwellers, regardless of social differences. The smelt, which became a sort of iconic fish of St. Petersburg, is the best example of this. In Vienna, fish was comparatively expensive and thus mainly consumed by wealthy people, except on special occasions such as Christmas.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles below.

The original virtual exhibition includes the option to switch between the cities St. Petersburg and Vienna within the individual chapters.

Fish consumption in St. Petersburg

The growing population of the young city very soon created a specific local culture of fish and seafood consumption. Peddlers delivered freshly caught fish to every courtyard and consequently this commodity has always been available to all urban dwellers.

As the sturgeon population decreased dramatically in the eighteenth century, salmon, whitefish, lamprey, and smelt became the major local fish species represented in St. Petersburg’s food consumption. We can identify several contexts in which the importance of local fish to local food culture and even local identity is evident, most particularly seasonality.

Smelt enter the Neva for spawning in spring and as a result this small fish became one of the symbols of spring in the city. The specific cucumber smell of this fish in the streets marks the annual revival of nature. Smelt was usually cooked in very simple ways—fried or boiled. Fried smelt could be pickled for long-term storage. Lamprey was another important target species for spring fisheries. Lamprey pickled in vinegar is recommended as a perfect appetizer in nineteenth-century cookbooks.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

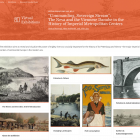

Smelt

The smelt was (and still is) normally fried in oil, and immediately served hot and crispy. This very simple recipe has been popular during all three centuries of St. Petersburg’s history.

Illustration by Nikolai Liberich.

© National Library of Russia. Used by permission.

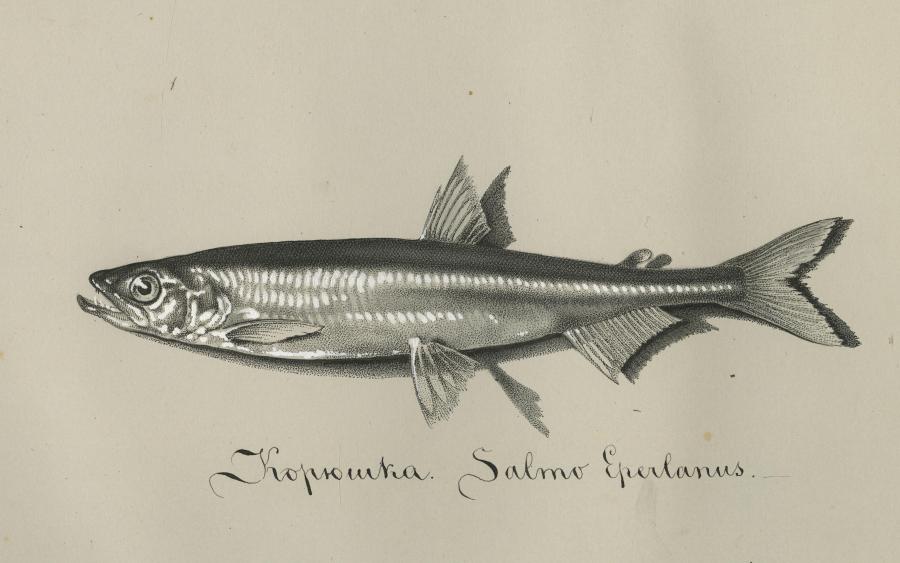

The Neva salmon

The Neva salmon had a superior reputation among the St. Petersburg fish-eaters. Salmon spawning season was the heyday of the short St. Petersburg summer.

Illustration by Nikolai Liberich.

© National Library of Russia. Used by permission.

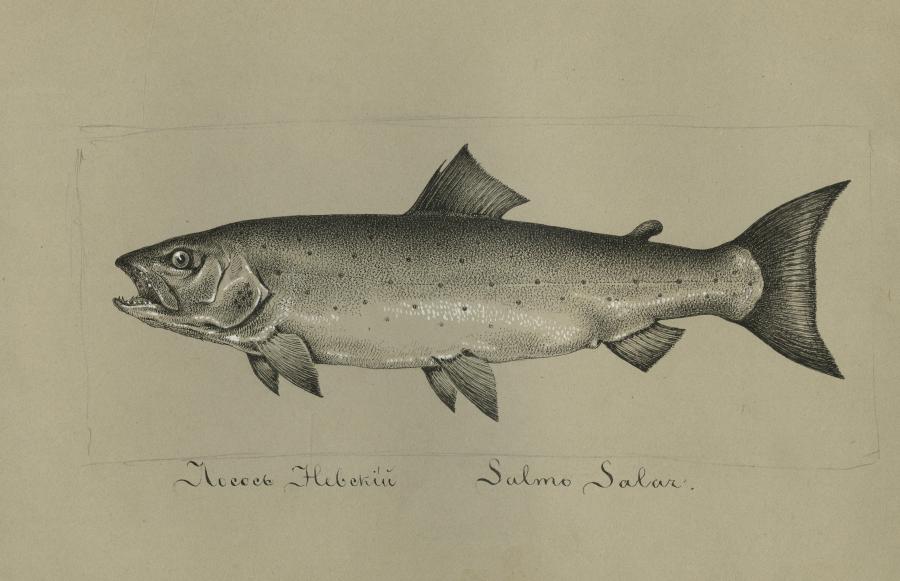

The Gatchina trout

The Gatchina trout was considered as perhaps the most delicious of all three species of trout living in St. Petersburg waters.

Illustration by Nikolai Liberich.

© National Library of Russia. Used by permission.

Salmon arrive to spawn in summer and St. Petersburg cooks used to distinguish between the Neva salmon and two kinds of local trout—the Neva trout and the Gatchina trout. The Neva trout was considered superb in terms of quality and taste, and it was recommended that it be cooked very fresh within a maximum of 10 minutes after it was killed. The Gatchina trout was smaller and it was recommended that this fish be killed about eight hours before it was to be cooked. In general, St. Petersburg cuisine included plenty of salmon and trout meals—boiled, salted, pâtés, soups, etc. Whitefish appeared in the catches more or less simultaneously with salmon and had a reputation of being one of the best local delicacies. The cookbooks recommended eating it boiled, fried, baked, stewed, smoked, and also salted. Whitefish pies were also very popular.

Apart from these four kinds of fish, the cookbooks also mention ryapushka (a small form of whitefish), Baltic herring, eel, and all sorts of freshwater fish abundant in the Neva and Lake Ladoga.

At the same time, the capital of an enormous empire, one of the most prosperous and luxurious cities in Europe, enjoyed a plentiful supply of fish from distant places in Russia and abroad. All sorts of sturgeon and sterlet from the Don and especially from the Volga formed the most luxurious part of the St. Petersburg fish market. The citizens also consumed a lot of imported herring, cod, and also seafood like oysters. This kind of commerce made visible the links between St. Petersburg, as a big port, and the ocean, as well as Europe, affirming its reputation as the most European city in Russia and at the same time undoubtedly Russian.

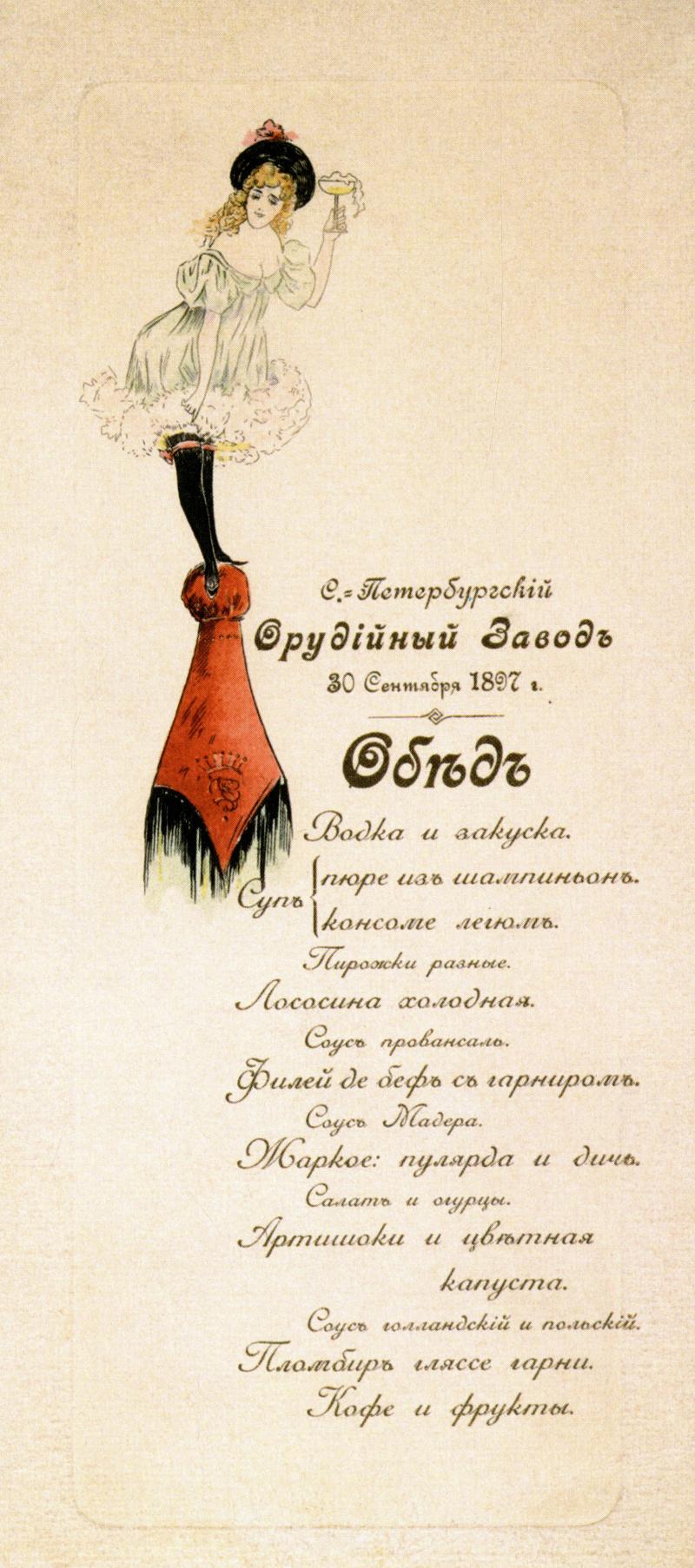

Factory dinner menu. Cold Salmon. The date of the dinner (30 September) falls within the period of the autumn spawning run and we may assume that the cooks used the fresh fish from the Neva. Unknown illustrator, 1897.

Factory dinner menu. Cold Salmon. The date of the dinner (30 September) falls within the period of the autumn spawning run and we may assume that the cooks used the fresh fish from the Neva. Unknown illustrator, 1897.

Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Menu of life-guards regiment. Gatchnia trout had a superb culinary reputation among St. Petersburg’s dwellers. The picturesque river, Izhora, not far from the imperial residence of Gatchina supplied delicacies not only to the imperial court but also to the officers of the elite life-guards regiment for the traditional summer reception. Unknown illustrator, 1883.

Menu of life-guards regiment. Gatchnia trout had a superb culinary reputation among St. Petersburg’s dwellers. The picturesque river, Izhora, not far from the imperial residence of Gatchina supplied delicacies not only to the imperial court but also to the officers of the elite life-guards regiment for the traditional summer reception. Unknown illustrator, 1883.

Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Fish consumption in Vienna

Until the end of the nineteenth century, the Viennese consumed mainly freshwater fish, which was undoubtedly a consequence of the city’s distance from marine environments. Fish prices were fixed until the 1790s and the price regulations provide valuable details about the different species that were eaten. Carp was the most important and was brought in large quantities from Bohemian and Moravian fish farms or from the Tisa in Hungary. Pike, pike-perch, and catfish appear in all price regulations, whereas other species have changed over time. The price regulation from 1632, for example, lists Danube salmon, sterlet, tench, and bream. About 100 years later—in 1736—prices were fixed for Danube salmon, burbot, ide, zingel, and cyprinid species. In 1756 one finds perch, bream, tench, barbel, crucian carp, but also brown and brook trout, which were likely brought from smaller, Alpine tributaries of the Danube; small fish such as bullhead, stone loach, minnow, chub, bleak, and even weather fish complete the list. Since there are no figures for total sales or consumption, it is difficult to identify whether these changes occurred due to a shortage of the larger fish or because of a change in preferences. For marine fish, the price regulations refer in particular to herring, stockfish, and flatfish.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische

The European catfish is one of the largest freshwater fish and a preferred food fish.

Illustration by George Bodenehr and Krüger. Originally published in Bloch, Marcus Elieser. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische. Berlin: Auf Kosten des Verfassers und in Commission bei dem Buchhändler Hr. Hesse, 1782–1795. Plate 34.

© Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien. Used by permission.

Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische

The pike is a widely distributed animal species and was one of the most preferred Danube fish.

Illustration by George Bodenehr and Krüger. Originally published in Bloch, Marcus Elieser. Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische. Berlin: Auf Kosten des Verfassers und in Commission bei dem Buchhändler Hr. Hesse, 1782–1795. Plate 32.

© Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien. Used by permission.

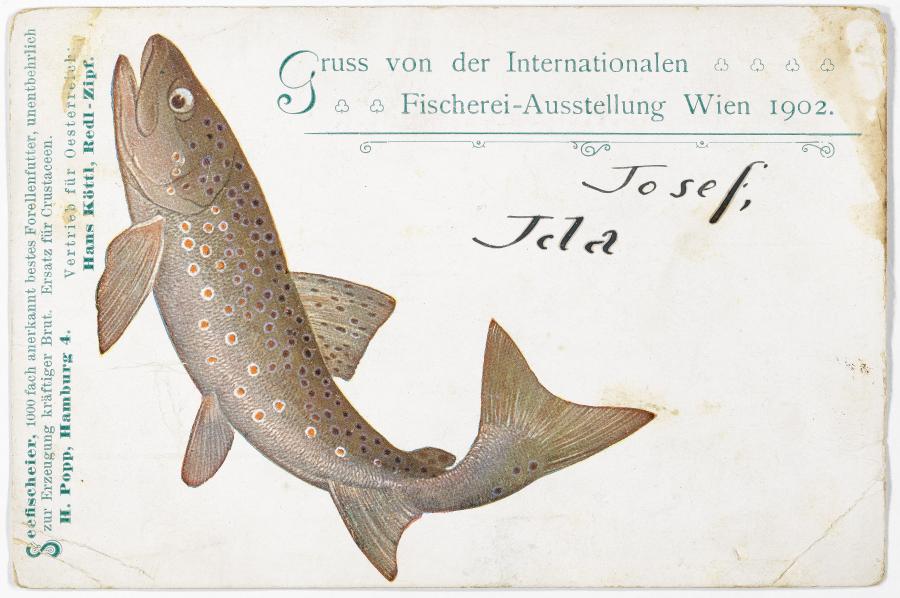

Grußkarte von der Internationalen Fischereiausstellung

This postcard depicting a trout was published on the occasion of the International Fisheries Exhibition in Vienna in 1902.

Unknown illustrator, 1902.

© Wien Museum, 173.846. Used by permission.

Beluga Sturgeon

A Beluga sturgeon, one of the most important Danube sturgeon species, caught in the Volga delta in 1993.

Unknown photographer, 1993.

© Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna. Used by permission.

Since the 1880s, detailed figures for fish brought to the central fish market have been available even at the species level. In the 1880s and 1890s, more or less the same fish as those named in the price regulations are found. The start of the marine fish trade in 1899–1900 is clearly visible. In the 1890s, their import became a goal of the urban administration in order to increase the supply of fish, which was considered an important protein source. Several attempts were undertaken to bring fish from the Adriatic Sea. Most, however, failed, mainly because of availability and transport problems. Hence, the largest share always came from the North Sea: the transport was easier and the fish stocks much richer. The opening of the “Nordsee Deutsche Dampffischerei-Gesellschaft” (Northsea German Steamfishery Company) in 1899 further encouraged trade in fish from this source.

In 1900 the proportion of marine fish in the total supply to the fish market rose abruptly to about 42 percent. By the beginning of World War One, the share had increased to more than 60 percent. Over the same period, the total amount of fish brought to the fish market rose from less than 800 metric tons to about 2,250 metric tons.

The total amounts of fish available in the nineteenth century show that the annual per-capita consumption of fish became surprisingly low. Until the 1860s, approximately 2 kilograms were consumed. Based on the amounts at the central fish market, as the main fish-trading place, yearly per-capita consumption dropped to 0.3 kilograms by the end of the nineteenth century. Then, the large-scale import of marine fish enabled the average value to double to 1 kilogram per year by the beginning of the first World War. The largest quantities of fish were sold around Easter and Christmas. Like many Austrians, the Viennese definitely preferred carp as a traditional Christmas dish.

One reason for the low consumption rates mentioned in several sources was the high price of fish in Vienna. The high prices reflect many developments, but were clearly also linked to availability. One fish trader reported in 1870 that prices had risen in previous years because many fish ponds had been transformed into arable land and the filling of Danube side arms had adversely affected fish reproduction and growth. In the 1880s, even carp was more expensive than, for instance pork meat; only dried or salted stockfish was cheaper.

In accordance with the information about the fish market, Austrian and Viennese cookbooks from the eighteenth to the late nineteenth centuries contain mainly recipes for freshwater fish. The largest diversity of recipes in all these books was for pike and carp. For the beluga sturgeon, different methods of preparation were suggested until the 1830s; thereafter the number of recipes decreased. Interestingly, this also coincides with the trends in the number of specimens brought to the market. In general, the number of fish species considered in the cookbooks decreased until the late nineteenth century. It increased again around 1900, when recipes for marine fish begin to appear alongside those for traditional freshwater fish.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles above.