Changing Landscapes and River Control

Unchannelized rivers are a dynamic environment where water and land constantly move. Living close to or even within riverine landscapes poses complex challenges. The river determines people’s lives to a great extent, shaping them spatially and temporally. In turn, societies have modified rivers considerably to secure their own needs and to overcome the risk of flooding. During the period of modernization in particular, new technologies offered unprecedented opportunities to change the nature of rivers. As important centers of technical expertise, Vienna and St. Petersburg eventually created almost new landscapes. This is particularly true for the history of the Viennese Danube. This section visualizes the changes in riverscapes essential to both capitals.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles below.

The original virtual exhibition includes the option to switch between the cities St. Petersburg and Vienna within the individual chapters.

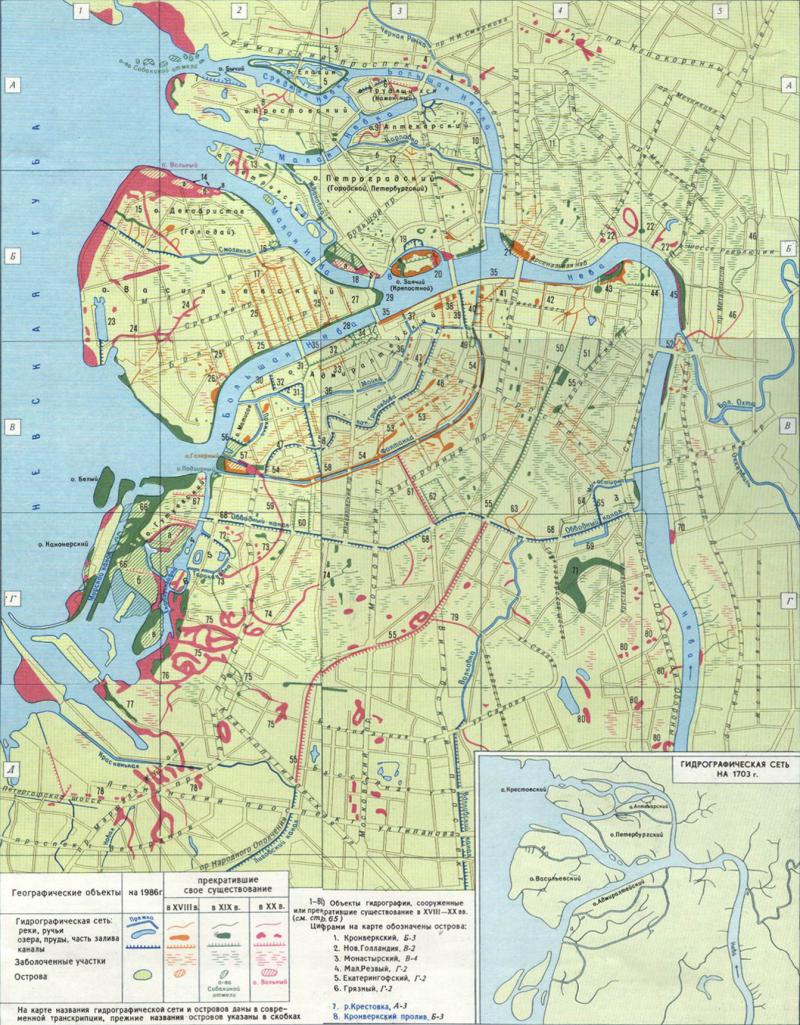

Map of St. Petersburg water objects, eighteenth–nineteenth centuries.

Map of St. Petersburg water objects, eighteenth–nineteenth centuries.

Unknown cartographer.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Changing riverscape of the Neva at St. Petersburg

St. Petersburg could not develop without significant changes to the waterscape. At least 80 hydrological objects appeared, disappeared, or were significantly changed between the early eighteenth and late twentieth centuries. This work required thousands of working hands, and a significant number of the workers who came to the new capital each year were involved in the building of canals and embankments. These were initially made of wood and later of granite. (This enormous work continues to the present day and seems unlikely to ever be totally completed.)

As a result, the rivers became significantly narrower (the Neva lost between 50 and 250 meters of width). The shallows were finally replaced with almost vertical granite walls, which undoubtedly affected the fish population.

While there were several permanent projects to change the riverine network in St. Petersburg, none can be called a “decisive” or “turning” point in its story. We can only list the most important projects: the transformation of the River Krivusha into the Ekaterininski Canal (now the Griboyedova Canal) in 1764–1790; the construction of the Obvodnyi Canal (1769–1833); the permanent raising of the ground level in almost all of the city throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; the construction of granite embankments on the Neva and the smaller rivers and canals (in the second half of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries); the construction and backfill of drainage canals and ponds; and the development of a network of bridges—made initially of wood and later of granite and steel.

The wooden bridges gradually disappeared in the nineteenth century and do not exist in the city anymore. Granite embankments appeared in the second half of the eighteenth century. Andrey Yefimovich Martynov, View of the Moika River by the Imperial Stables, 1809. Watercolour and Indian ink, 60 x 86 cm.

The wooden bridges gradually disappeared in the nineteenth century and do not exist in the city anymore. Granite embankments appeared in the second half of the eighteenth century. Andrey Yefimovich Martynov, View of the Moika River by the Imperial Stables, 1809. Watercolour and Indian ink, 60 x 86 cm.

© The State Hermitage Museum

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Water control in St. Petersburg required the skills of numerous experts and it was therefore one of the most important spheres of Russian-European technological transfers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Dutch and Venetian engineers were invited in the early days of the city and Russian students were sent abroad for training. Later, many French and German hydroengineers worked in St. Petersburg, as well as the graduates of the technical institutes created in the city itself. By the early twentieth century, St. Petersburg had itself begun to export hydrotechnologies abroad.

Water transportation

Water routes, both natural and artificial, became the basis for St. Petersburg’s transportation system early on in the life of the city. Ground transportation was almost impossible due to the poor quality of the few available roads. Barges delivered food for workers and construction materials for buildings, as well as commodities for the growing commercial seaport. Water transportation very soon became an important branch of business in the city and throughout the imperial period: the Neva and its branches were dotted, from April to November, with

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

private boats as well as big transportation vessels. In addition to the privately owned vessels, many city administrations possessed boats for their officials, and this was an important part of the urban transportation system, too.

Dredge on the Fontanka

The Anichkov Bridge was rebuilt several times between the early eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries. Steam-powered dredges appeared in the middle of the nineteenth century; previously the rivers had been cleaned manually.

Weierman, Dredge on the Fontanka, 1869. Illustration from the journal Vsemirnaia illustraciia, 1869.

Public domain.

The Islands of the Neva

This painting depicts St. Petersburg nobility’s recreational zone with numerous impressive mansions and richly decorated pleasure boats. The steamboats seen in the painting were used in the first half of the nineteenth century to serve as transportation inside the city and in the Gulf of Finland.

T. A. Vasiliev, View of Islands in St Petersburg, 1820. Oil on canvas, 83 x 114 cm.

© The State Hermitage Museum. Used by permission.

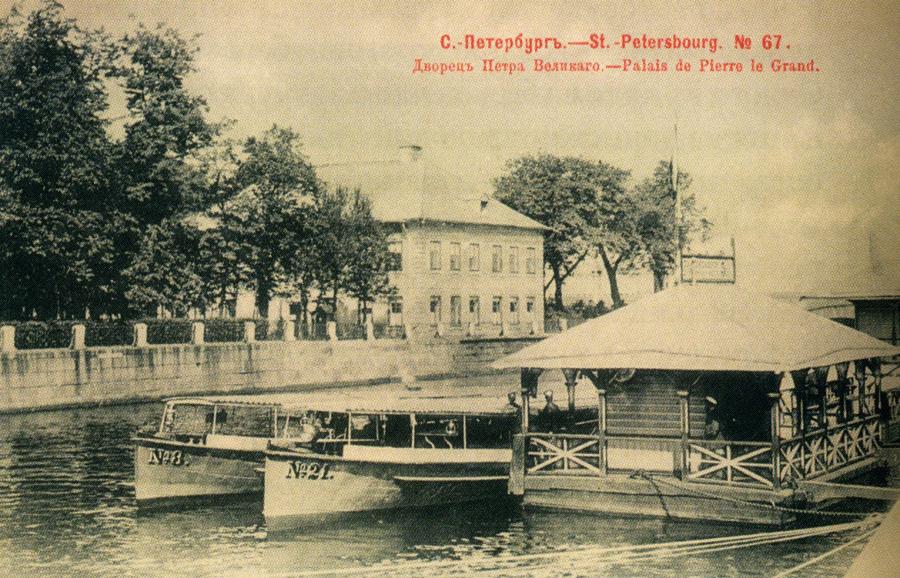

Postcard of steamboats on the Fontanka, near the Summer Garden, early twentieth century

This pier no longer exists, and public transportation in this part of the city is no longer available.

Postcard of steamboats on the Fontanka, near the Summer Garden, early twentieth century.

© The State Museum Reserve “Peterhof,” 2 Razvodnaya Str., Peterhof, Petrodvorets district, St. Petersburg, 198516. KП 69900/39. Used by permission.

Postcard of the Fontanka near the Anichkov Bridge, early twentieth century

This postcard shows barges, a tugboat, and steamboats near the Anichkov Bridge. Barges delivered thousands of tons of commodities to the city, including fuel timber, which was very important for the northern city. Tugboats were used for the transportation of commodities within the city. Steamboats were an important part of public transportation for millions of passengers annually.

Postcard of the Fontanka near the Anichkov Bridge, early twentieth century.

© The State Museum Reserve “Peterhof,” 2 Razvodnaya Str., Peterhof, Petrodvorets district, St. Petersburg, 198516. KП 70172/58. Used by permission.

In the nineteenth century, new technologies came to the city. In November 1815, the first steamboat, Elizaveta, initiated a new era in the history of St. Petersburg’s water transportation. From that moment until 1917, the smoke from numerous steamboats became a characteristic part of the city’s atmosphere. These vessels were built in the city and delivered to St. Petersburg from the shipyards of central Russia, as well as from abroad. Steamboat transportation expanded the borders of St. Petersburg and made certain territories easily accessible, which were otherwise quite remote in the eyes of eighteenth-century citizens.

Floods

The Neva floods constitute an important part of the St. Petersburg collective memory materialized in numerous heritage objects throughout the city. This stone tablet on the wall demonstrates the water level during the most catastrophic flood in the St. Petersburg history that took place in November 1824. These tablets are still quite visible in the central part of the city and therefore the space of urban memory is still very much shaped by the centuries of threat from the unpredictable stream. Photograph by BiOBER.

The Neva floods constitute an important part of the St. Petersburg collective memory materialized in numerous heritage objects throughout the city. This stone tablet on the wall demonstrates the water level during the most catastrophic flood in the St. Petersburg history that took place in November 1824. These tablets are still quite visible in the central part of the city and therefore the space of urban memory is still very much shaped by the centuries of threat from the unpredictable stream. Photograph by BiOBER.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 27 November 2018. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Neva is quite a self-willed stream with very unstable water levels. The downstream is strongly affected by the Gulf of Finland. In autumn, low atmospheric pressure combines with stormy wind from the west to form cyclones. As a result, enormous masses of water enter the mouth of the Neva from the sea and the river floods the city. The most catastrophic flood took place on 7 November 1824, when the water level rose 4.21 meters above the norm. For centuries, floods have been an important part of local culture and identity, hanging over the city like the Sword of Damocles. To a great extent, the idea of flood protection has been the driving force behind waterscape changes since the eighteenth century. Engineers tried to develop canal networks in order to prevent water stagnation, which was considered to be the major reason for floods; however, it was only in the twenty-first century that a dam was built across the Neva inlet, radically changing the eastern part of the Gulf. The threat has thus been eliminated as no water can now enter the mouth of the river from downstream.

Changing riverscape of the Viennese Danube

Like many urban rivers, the Danube served as the main emporium supplying the city with goods. Hinterlands located up- and downstream delivered grains, animals, meat, vegetables, fruits, or commercial goods such as wood and various other items. The Danube and its urban tributaries also served as locations for waste disposal and sewage discharge. Its waters powered ship mills along the northern river arm on the riverbanks opposite the urban center.

It is difficult to speak about the “Viennese Danube” as such prior to the great Viennese Danube regulation. Until then, the river consisted of several arms, along with many islands and flat riverbanks that were not stable, but moved and changed their location with each larger flood.

The greatest hive of activity was concentrated on the river canal next to the city center. Today, it is known as the “Donaukanal,” or “Danube Canal.” This was the main river arm until early modern times, but because of natural processes, the whole river system shifted towards the north. Intensive technical and financial efforts to keep the main canal in the city were abandoned in the eighteenth century. Until the great Danube regulation, the Donaukanal remained the town’s main and most vibrant river arm.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

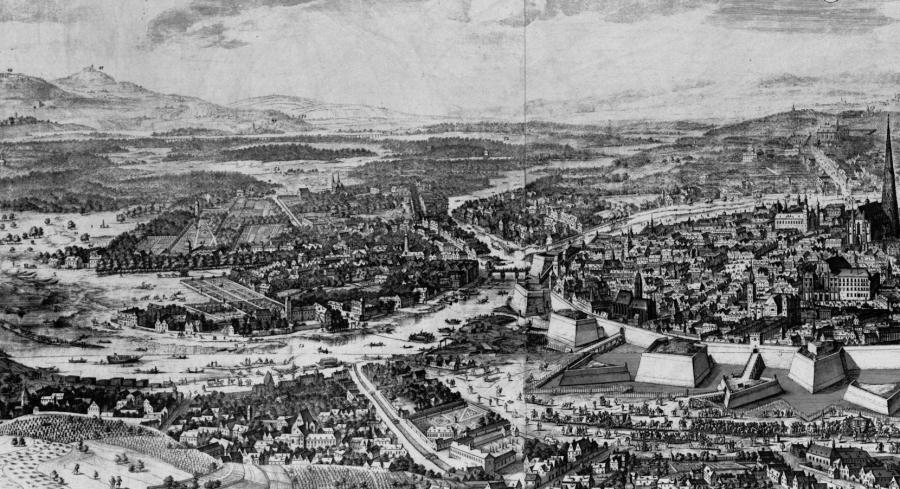

Vogelschau der Stadt Wien und Umgebung

View of Vienna and the Donaukanal around 1683. Wooden ships and rafts can be seen on the former main canal of the Danube, now called the “Donaukanal.” A ferry connected the banks.

Folbert van Alten-Allen, Vogelschau der Stadt Wien und Umgebung [Bird’s eye view of the city of Vienna and surroundings], around 1683.

© Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv, Pläne und Karten: Sammelbestand, P1: 1856. Used by permission.

Prospecte und Abrisse einiger Gebäude von Wien

Palaces and parks were built on the banks of the Donaukanal, as for instance the Palais Althan. In the center of the foreground, horses are pulling a ship upstream.

Illustration by Johann Fischer von Erlach and Johann Adam Delsenbach. Originally published in von Erlach, Johann Fischer, and Johann Adam Delsenbach. Prospecte und Abriße einiger Gebäude von Wien. Vienna, 1719: 33.

Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Wien, AC06593649. Accessed on 21 January 2019. Click here to view source. CC BY-NC 2.0 AT.

Ansicht des Schanzels an der Donau

The Donaukanal was Vienna’s main supply route for wood, among other commodities.

Johann Ziegler, Ansicht des Schanzels an der Donau, 1779.

CC0. Courtesy of Wien Museum.

Obstmarkt am Schanzl

In addition to fish, also fruits, vegetables, and animals were sold along the Donaukanal. Imported from villages upstream, these goods were sold directly on the river banks. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth century several bridges were built to cross the Donaukanal (see background).

Friedrich Alois Schönn, Obstmarkt am Schanzl, 1895.

CC BY 4.0. Courtesy of Wien Museum.

Despite the various riverine benefits, Danube floods were a permanent threat to the riparian residents and their infrastructures. Floods occurred due to heavy rainfall or due to fast-melting snow upstream. The regular ice jam floods in late winter were particularly destructive. Flood protection dykes had already been erected in the late eighteenth century, but proved to be insufficient. At that time, people relied mainly on passive practices. When a flood was expected, boats were readied to evacuate people, and wood was prepared for catwalks and to brace houses. Bakers, butchers, and commercial food traders in threatened places were obliged to store flour, wood, and water. When floods were believed to be imminent, house owners were ordered to ensure that elderly and ill people were moved to upper floors. Likewise, animals had to be taken to safe locations. During floods, soldiers were obliged to observe the water level and report houses at risk of collapse.

Ice floods and ice jams were typical for the unchannelized Danube. Adolf Obermüller and Alexander Bensa, Der Donaueisstoß bei Wien im Januar 1880 [The Danube ice jam near Vienna in January 1880], 1880.

Ice floods and ice jams were typical for the unchannelized Danube. Adolf Obermüller and Alexander Bensa, Der Donaueisstoß bei Wien im Januar 1880 [The Danube ice jam near Vienna in January 1880], 1880.

Courtesy of Wien Museum.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

These flood protection practices changed throughout the nineteenth century. Projects for a systematic channelization of the Danube were developed beginning in 1815. They linked flood protection and the improvement of shipping, as well as the erection of stable bridges crossing all Danube arms. Financial constraints and disagreements between engineers and decision-makers hampered all these projects for several decades.

Finally, between 1870 and 1875, the great Danube regulation was implemented in Vienna. It transformed the dynamic riverine landscape into a straight riverbed, thereby also changing fish habitats. The Donaukanal remained as a river arm, although it was not sufficient for larger ships, particularly steamships, which had more challenging technical requirements than the old wooden rowing ships and rafts. Shipping and landing places had to be transferred to the new main Danube riverbed.

View of the Danube River from Nussdorf after the Great Danube Regulation. Anton Hlavacek, Die Kaiserstadt an der Donau, 1884.

View of the Danube River from Nussdorf after the Great Danube Regulation. Anton Hlavacek, Die Kaiserstadt an der Donau, 1884.

Courtesy of Wien Museum.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The newly stabilized terrestrial areas in the Viennese Danube floodplains became an important land resource in the fast-growing and industrializing city. In the following decades, the districts located here showed the highest growth rates of urban land and population. Flood events of the 1890s, along with increasing knowledge about the hydrology of the river, proved that the measures implemented in the 1870s were insufficient to protect urban residents from floods.

A continuous effort was made to improve flood protection measures from the second half of the nineteenth century. Additional projects continue to be implemented today.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles above.