Jefferies, Richard. After London; or, Wild England. London: Duckworth & Co, 1905.

First published 1885 by Cassell and Company. “It became green everywhere in the first spring, after London ended.” So begins Richard Jefferies’s After London, an early example of what we would today call the “eco-apocalyptic” novel. (In its own day, the book was commonly understood as “romance” or “fantasy.”) After growing up on a rural farm near Swindon, England, Jefferies became a celebrated naturalist, “a major contributor to the social history of rural England,” and “perhaps the most brilliant imaginative observer of trees and animals and flowers and weather in his century,” as Raymond Williams describes him in The Country and the City. Jefferies was also a prolific writer, publishing numerous essays for local newspapers and the Pall Mall Gazette, a London-based evening newspaper whose other contributors included HG Wells, another pioneer of apocalyptic fiction; children’s books (Wood Magic: A Fable; Bevis: The Story of a Boy); and a philosophical autobiography (The Story of My Heart), to name only a sample of his works. The following passage from Jefferies’s autobiography, describing his climb up one of his favorite countryside hills, showcases a lyrical, almost mystical relationship to nature:

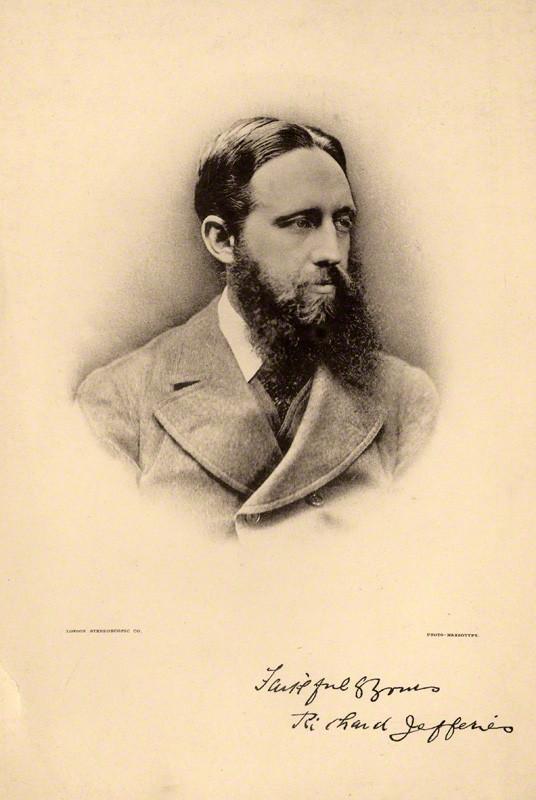

John Richard Jefferies, 1848-1887

John Richard Jefferies, 1848-1887

Image made available on the Environment & Society Portal for educationally purposes only, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Moving up the sweet short turf, at every step my heart seemed to obtain a wider horizon of feeling; with every inhalation of rich pure air, a deeper desire. The very light of the sun was whiter and more brilliant here. By the time I had reached the summit I had entirely forgotten the petty circumstances and the annoyances of existence. I felt myself, myself.

— Richard Jefferies, The Story of My Heart

It might be expected that anyone for whom nature was so revelatory hated the city and, more broadly, the modern industrialism that made England the “workshop of the world” in the nineteenth century. But Jefferies usually didn’t see pastoralism and urbanism as contradictory. “I dream in London quite as much as in the woodlands,” he once wrote to a friend. Yet what makes After London so memorable is the obvious satisfaction with which Jefferies describes the city’s end. In the novel’s first part, “The Relapse into Barbarism,” Jefferies uses his extensive environmental knowledge to describe, in joyful detail, nature’s immense expansion in the aftermath of a mysterious cataclysm that has depopulated London:

The meadows were green, and so was the rising wheat which had been sown, but which neither had nor would receive any further care. […] By the thirtieth year [after the disaster] there was not one single open place, the hills only excepted, where a man could walk, unless he followed the tracks of wild creatures or cut himself a path. […] Flood[s], carrying the balks before it like battering rams, cracked and split the bridges of solid stone which the ancients had built. […] Thus, too, the sites of many villages and towns that anciently existed along the rivers, or on the lower lands adjoining, were concealed by the water and the mud it brought with it. From an elevation, therefore, there was nothing visible but endless forest and marsh.

— Richard Jefferies, After London

And what of London itself? “For this marvelous city, of which such legends are related, was after all only of brick, and when the ivy grew over and trees and shrubs sprang up, and, lastly, the waters underneath burst in, this huge metropolis was soon overthrown.”

Beneath such descriptions, as though hidden under Jefferies’s marshes and weeds, is a complex desire for an alternative to industrial civilization—for a new world. Appropriately, one of Jefferies’s readers reported: “absurd hopes curled around my heart as I read it. […] I want to see the game played out.” The reader was William Morris, who would indeed play the game out in his News From Nowhere (1890), perhaps the greatest pastoral utopia ever written.

To read the book, follow the link to Project Gutenberg. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net.

- Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.