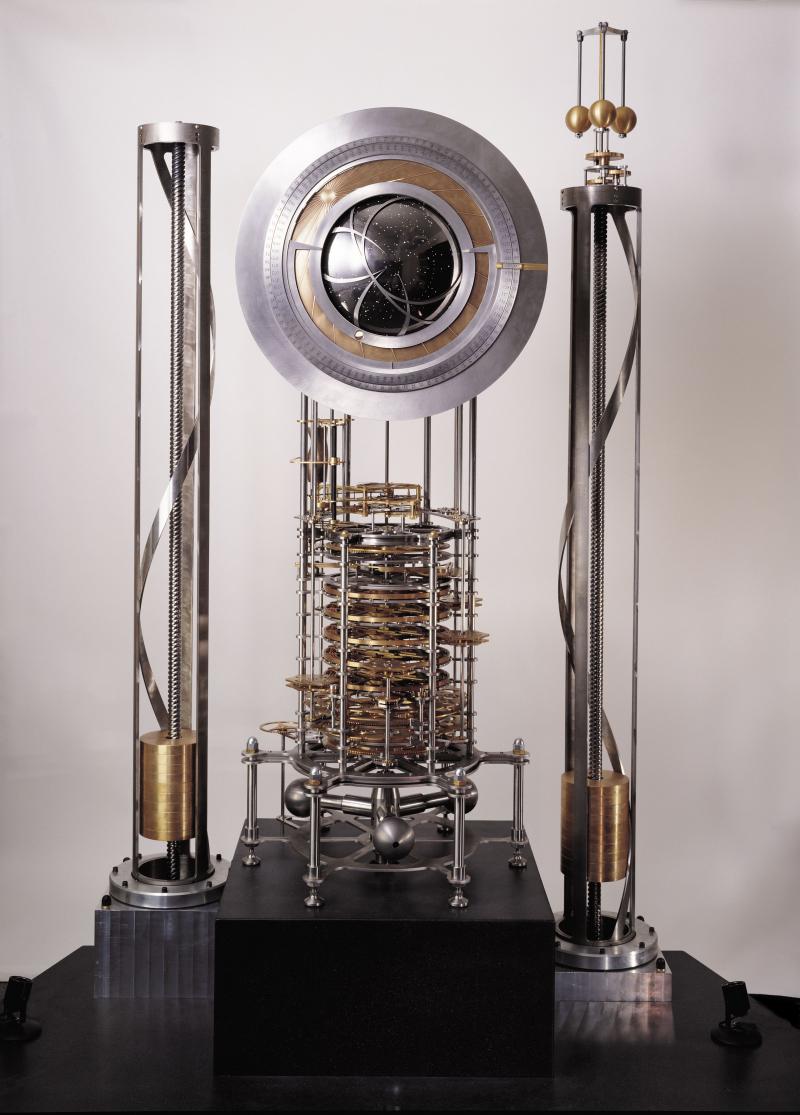

Clock of the Long Now

Now is the period in which people feel they live and act and have responsibility. For most of us now is about a week, sometimes a year.…Just as the Earth photographs [taken from the Apollo space missions in the 1970s] gave us a sense of the big here, we need things that give people a sense of the long now.

Stewart Brand, US author and initiator of the Clock of the Long Now

“Live in the here and now” is a common expression in our time. Over the course of the twentieth century in particular, the intervals in which we experience time have become increasingly shorter. New technologies frequently become obsolete within a single year, fashion trends last no more than a single season, companies think in terms of quarters, and politicians only until the next election season. The US computer engineer Danny Hillis and the author and environmental activist Stewart Brand wanted to do something to counteract this habit of short-term thinking. We need something to encourage us to think over the long term and remind us of the far-reaching temporal effects of our actions: the idea of the Clock of the Long Now was born.

The Idea

Installed in a vertical shaft drilled into a mountain in Texas, the giant mechanical clock will tick only every ten seconds. Visitors that climb the strenuous path to the Clock provide its chiming mechanism with energy, which results in a melody playing at noon. A special algorithm calculates the melody—a different one each time.

The clock is both an ambitious engineering project and a symbol. It should last for the extent of the “long now,” that is, at least 10,000 years. But this is not really the reason that the Long Now Foundation has undertaken this complex project. Instead, it should encourage people today to reflect upon their world and expand their temporal horizons: “By building something like a 10,000 year clock, you start to get a different perspective on how you might change those options [of generations of the far future].” (Alexander Rose, Clock Project Manager, Introduction to the Long Now Foundation, 2010)

The monumental Clock, some 60 meters in height, will be built into a remote limestone mountain in Texas. To reach it, visitors will have to walk through a tunnel into the mountain to reach continuous spiral staircases carved out of the rock. During the ascent, they will pass the different parts of the Clock until they reach its face at the top.

The monumental Clock, some 60 meters in height, will be built into a remote limestone mountain in Texas. To reach it, visitors will have to walk through a tunnel into the mountain to reach continuous spiral staircases carved out of the rock. During the ascent, they will pass the different parts of the Clock until they reach its face at the top.

Courtesy of the Long Now Foundation

From Idea to Reality

Much thought must go into the construction of a machine that will remain functional longer than any object that has yet been made by humans. Danny Hillis and his team developed a set of fundamental principles to ensure its accuracy and durability. The clock should be made of long-lasting materials such as stainless steel and titanium; it should able to be maintained using Bronze Age technology if needed. Its manner of operation must be clear and capable of being improved, and it should be possible to construct clocks of various sizes based on the same basic design.

One of the most important considerations, however, is how to provide the clock with a constant source of energy. How can the Clock of the Long Now continue to operate for hundreds of years? The Clock’s engineers have decided to use human visitors as a source of power as well as other natural energy sources. Part of the energy comes from using temperature differences. A window cut into the mountain peak lets in sunlight, which heats a sealed air chamber; the resulting pressure difference drives a piston which adjusts the Clock and provides energy.

The clock face shows the year written in five digits; after all, the Clock has to be able to show dates past the year 10,000. In addition, it shows astronomical events, such as the sun’s position during the course of the 24-hour solar day, the moon phases, and the position of sunrise/sunset and moonrise/moonset, which change during the course of the year along with the seasons.

The chimes are created from more than 3.5 million different combinations using 10 bells. But it only chimes when the Clock has stored enough excess energy, or when human visitors have wound it.

Although the Clock keeps time even when humans are absent, to save energy its hands only move to display the time when visitors wind up the dials. If no humans visit, the display remains still, but the Clock does not. Thanks to stored energy, it will continue to operate even if the sun is hidden for a time and the sky darkens, for example, due to volcanic eruptions, a nuclear winter, or meteorite impacts.

For Alexander Rose, manager of the project, the Clock is, above all, about hope, for it suggests that there will still be humans on the planet even in the far future. But the lives of these humans 100, 1,000, or 5,000 years from now will be shaped by the decisions that we make today.