Introduction: “Quite a chapter in the history of the West”

Map of the Burlington Route. Created by Rand, McNally & Co., 1892.

Map of the Burlington Route. Created by Rand, McNally & Co., 1892.

Courtesy of Newberry Library.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This map shows the extent of the Burlington Route during a mythic moment in American history. In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his influential essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” at a meeting of the American Historical Association in Chicago, during the World’s Colombian Exposition. Turner’s essay was prompted by a statement in the Superintendent’s Bulletin of the Census for 1890 declaring that the frontier line that had marked the advance of settlement westward until the 1880 census was no longer discernible and would stop appearing in the census reports. Turner wrote:

Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.

While Turner’s essay worked at a large geographic scale, it broke down quickly upon closer examination. The power of Turner’s thesis lay not in its accuracy or ability to explain or predict, but rather its rhetorical brilliance articulating what many people believed at the time. The end of the frontier created an existential crisis for Turner and influential Americans, including future President Theodore Roosevelt. It helped ignite a national passion for experiencing and preserving what was left of the “wilderness.” The railroads would capitalize on this, and were strong advocates and promoters of national parks and wilderness. Of course, people would have to travel by train to get there. Ironically, the railroads also played a leading role in developing the vast lands along their tracks, radically transforming the landscapes people would soon seek to escape.

Meanwhile, the emigration patterns had shifted from western and northern Europe to eastern and southern Europe. Since there were fewer opportunities on the agricultural frontier, the newer immigrants settled in the cities. Large ethnic enclaves in cities seemed to confirm the belief that the frontier experience had fostered assimilation. What Turner and others overlooked was the overwhelming evidence of rural ethnic enclaves that persisted well into the twentieth century in many areas. Indeed, the Burlington railroad encouraged colonies from Europe to emigrate and settle together because they believed strong communities increased the likelihood of success. The iconic yeoman farmer striking out on his own was less likely to stay on the land. The Burlington even helped establish churches, often vitally important in maintaining ethnic group identities.

Another sign of the vanishing frontier was the Wounded Knee Massacre at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota on 29 December 1890. This tragic event symbolized the end of the long and often bloody conflicts as treaty makers, the US Army, and waves of European and American settlers forced Native Americans from their lands onto reservations. Note the remnant of Indian Territory on the 1892 map that would soon become part of Oklahoma.

While Turner, Teddy Roosevelt, and others fretted that the crucible of the Frontier would no longer be forging strong, manly, and uniquely American characters, and Native Americans were forced into poverty as settlers claimed their best lands, the readers of the Burlington Route map probably saw something more hopeful—a chance to escape from where they were, permanently, temporarily, or even imaginatively. Tourists saw a route to adventure, a chance to glimpse and possibly participate in what was left of the frontier. Potential settlers saw a road to a farm of their own, or the chance to be part of a growing new city. The rails transported people and goods further westward, beyond the Great Plains where the frontier line broke apart, to Denver, Cheyenne, and Sheridan, to California and the Pacific Northwest, “the land of opportunity now” (as the advertising department dubbed it). Railway brochures assured readers that they could still get to the promised land on a train.

The federal government offered large swaths of the public domain lands to railway companies to encourage them to lay tracks through sparsely settled regions of the country. The first land grant was made to the Illinois Central Railroad in 1850. Subsequently, grants were issued to the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad to build a line across Missouri, and the Burlington received land grants in Iowa and Nebraska. To realize profits the railroad company needed to not only sell the land but also encourage its settlement and development. Toward this end, the Burlington aimed their advertisements toward ambitious people, regardless of race, class, or religion. Railway publications, promoting places to tourists and settlers, make up an important part of the booster literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The genre helped shape the way people perceived and experienced the land.

The development of railroads and the placement of rail corridors were vitally important to the establishment and growth of cities. The 1890 census revealed that Chicago had become the second largest city in the United States with over one million inhabitants. More than any other American city, Chicago was built by the railroads. Between 1840 and 1850 the population of Chicago increased from 9,000 to almost 30,000. The town was booming, in part because of the completion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848 linking the Great Lakes seaway with the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. While water transportation was important, lakes and rivers tended to freeze in the winter. Furthermore, early roads were virtually impassable in the spring and during wet weather. For Chicago, railways offered the promise of year-round transportation. Railroads turned Chicago from a city into a metropolis, connecting it to Northwoods lumber, midwestern and Great Plains grain and livestock—transforming Chicago into the center of lumber, grain, and meat processing. The production, processing, and transportation of these commodities profoundly shaped the landscapes of the American Middle West and Far West.

Advertisement poster for CB&Q Railroad. Created by Knight & Leonard, n.d.

Advertisement poster for CB&Q Railroad. Created by Knight & Leonard, n.d.

Courtesy of Newberry Library.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy was formed in 1855 from the Aurora Branch Railroad, and was directed by Boston financier John Murray Forbes and managed by Charles Elliot Perkins. The name suggested its westward focus, aiming two roads across the Mississippi River: one at Burlington, Iowa, the other to the south at Quincy, Illinois. The Burlington & Missouri River Rail Road was formed to build tracks across southern Iowa to eventually span the Missouri River and carry on into Nebraska. The road at Quincy connected to the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad, which cooperated with the CB&Q and was eventually absorbed into its system. While the B&MR RR was still seeking investors, the H&StJo obtained a land grant and built a road across northern Missouri. One of its Hannibal backers was John M. Clemons. Clemons’s son later went by the pen name Mark Twain.

The CB&Q was usually simply called “the Burlington.” The company itself referred to its system as “the Burlington Route.” The company’s corporate history is complex, the Burlington was an often amorphous entity, pieced together methodically over time, forming alliances and absorbing other companies. Even when railroad baron James J. Hill acquired controlling interest in the company in 1901, the Burlington maintained a distinct identity as a Granger Railroad—strongly associated with farmers and ranchers in the American agricultural heartland, while enjoying the transcontinental reach of Empire Builder Hill’s Great Northern Railway and Northern Pacific, which extended the Burlington Route into the Pacific Northwest. In 1908 the Burlington gained control of the Colorado & Southern Railway, extending the system through Texas to the Gulf of Mexico. In a testament to the durability of the Burlington brand, when the CB&Q, Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Spokane, Portland & Seattle railroads merged in 1970 they became the Burlington Northern.

Those involved in the early development of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad were aware of their role in transforming the American heartland. Attached to a bundle of documents representing the final report of the CB&Q’s land department, railroad historian Richard C. Overton found a memo dated 8 January 1906 from W. W. Baldwin to Charles E. Perkins. The memo began:

This closes quite a chapter in the history of the West. I wish I had time to write a history of the two Burlington Land Grants and discuss them from the standpoint of the public good, as compared with probable conditions if the lands had been subject to homestead entry and private sale. It is a large subject, and one on which there is much general misinformation.

Beneath this, Perkins wrote: “You ought to write a history of it for sure—even if only a brief one.” But, as Overton wrote in the introduction to the first of his two major books on the CB&Q, Burlington West: A Colonization History of the Burlington Road (1941, 3), neither man lived long enough to write a history of the road. The exchange between Baldwin and Perkins reveals their confidence not only in the importance of the history of the road, but also that such a history would present the company in a positive light.

In 1936 the company began to make its historical records available by depositing about six tons of documents in the Baker Library at Harvard, later adding material from the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad. In 1943, they deposited ten tons of documents at the Newberry Library, in Chicago. In 1946 the company moved its files from the Baker Library to consolidate the CB&Q collection at the Newberry Library. In his 1941 book, Overton referred to this collection as an “overwhelming mass of material.” Today, it is even larger. With subsequent additions, the CB&Q collection at the Newberry consists of some 2,760 linear feet (840 meters) of documents representing an important part of the history of the midwestern, Great Plains, and Mountain States history, from 1847 to 1965. Most of the collection has not yet been processed; many bundles are still wrapped in string tied by CB&Q employees several decades ago.

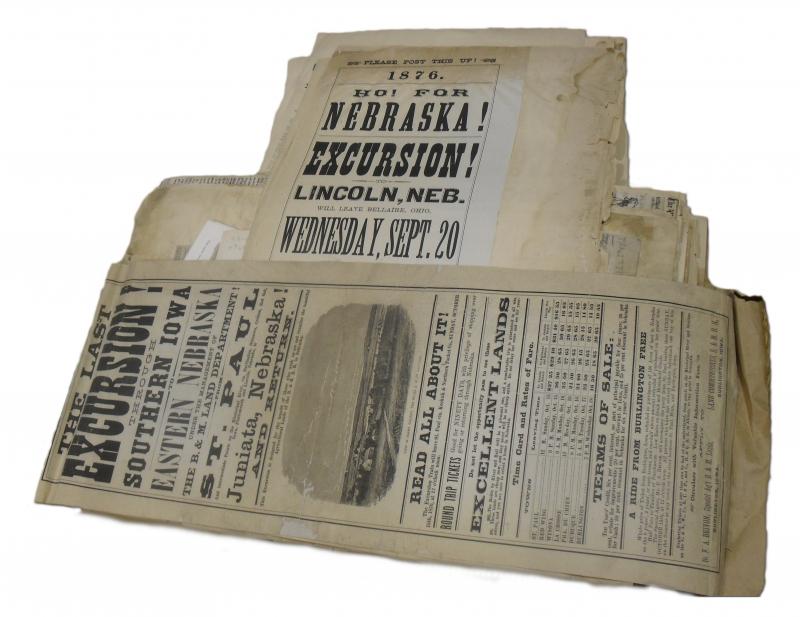

Stack of CB&Q advertising posters.

Stack of CB&Q advertising posters.

Courtesy of Newberry Library.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This virtual exhibit aims to provide a tiny glimpse of the types of documents that await discovery by environmental historians, historical geographers, and others interested in the promotion and transformation of landscapes. It represents merely a few ounces out of several tons of documents—not even the tip of the tip of the iceberg—so it is by necessity selective, focusing on visually interesting materials that represent topics relevant to the promotion and transformation of landscapes. With few exceptions, such as Cronon’s use of the collection for his seminal environmental history Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991), the collection remains underused by environmental historians. This is unfortunate, because directly and indirectly railroads were arguably the most important engine of environmental changes during the second half of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century. Documentary evidence to address key questions of environmental history awaits discovery and analysis.

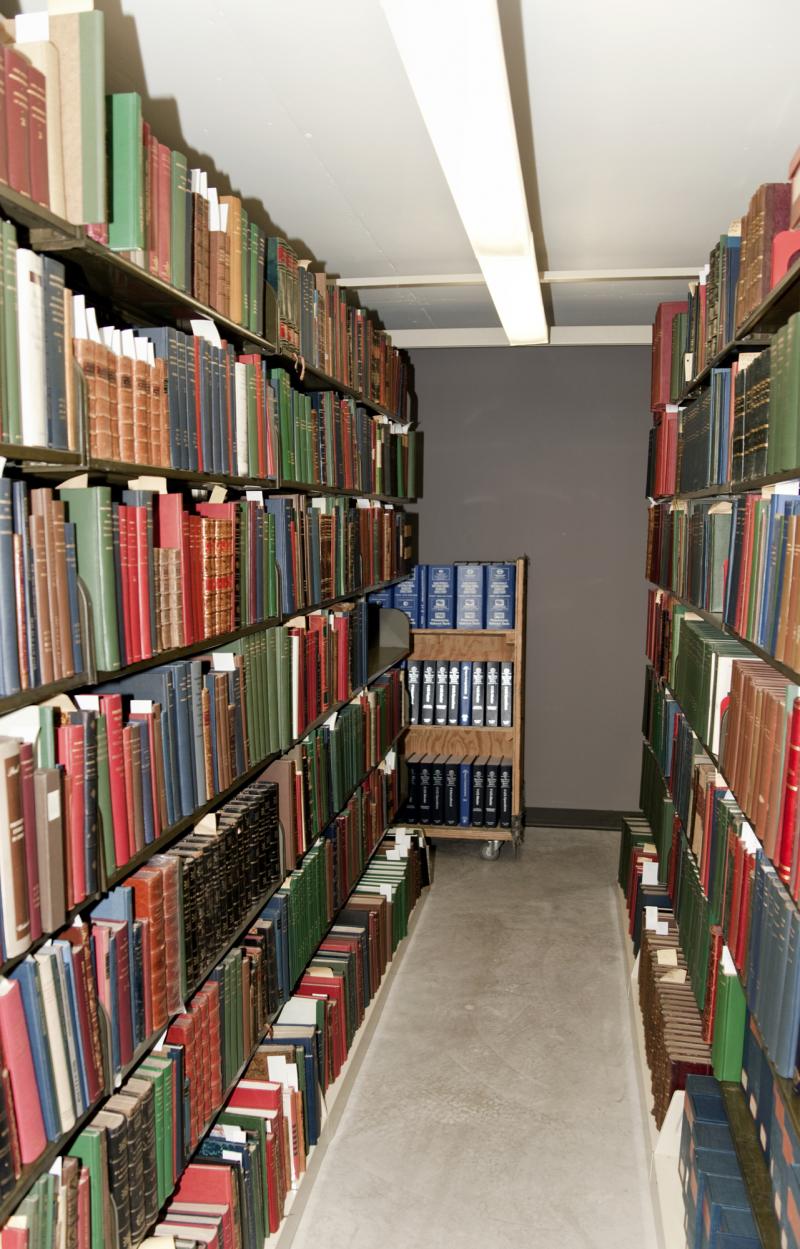

An aisle of the CB&Q archive at the Newberry Library, 2011.

An aisle of the CB&Q archive at the Newberry Library, 2011.

Courtesy of Newberry Library.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

A well organized company, the Burlington kept meticulous records of all aspects of its business. Land survey records corrected and augmented original Public Land Surveys, while carefully documenting ecological and cultural features before massive settlement. They maintained records of flooding and water levels of rivers traversed by their trains. As the companies laid track, built bridges, and ran their trains they consumed massive amounts of iron, steel, coal, and timber. The company acquired and operated coal mines, leaving maps and daily records of the operations. Land commissioner records contain volumes of correspondence regarding the company’s effort to sell and settle their landholdings, and their programs to build lasting communities and agricultural economies connected to distant markets by their rail lines. The company diligently recorded what was carried over their tracks, as grain, cattle, ore, and other products moved east, and manufactured goods moved west. Just as railroad publications informed and shaped views of the lands they settled, they also promoted tourism and travel. The Burlington hired popular authors, painters, and photographers to contribute to publications meant to promote tourism to national parks, and to inform and shape the experience of passengers as they traveled these routes.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter