Locating

The story of Lily Stearns illustrates how nature and culture combined to shape opportunities on the land. Her struggle to sink roots in Montana contextualizes the larger economic, social, and environmental challenges for those who envisioned taming the land—and themselves—in the face of larger climatic and geopolitical forces.

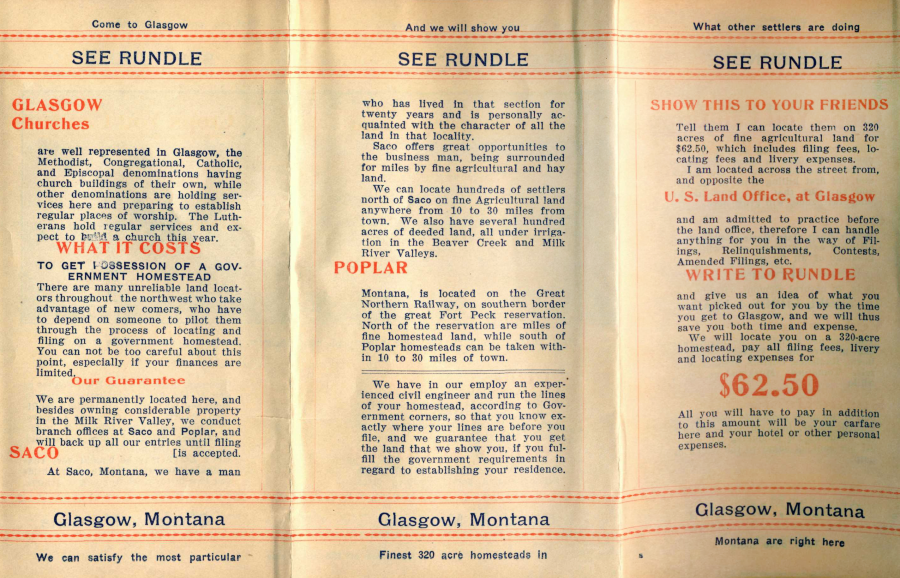

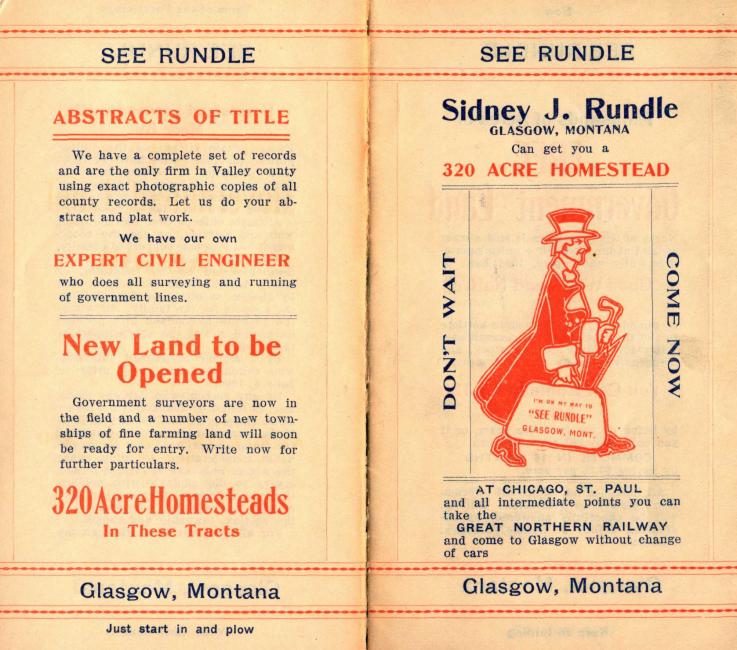

Stearns (née Lily Bell Murray, and legally divorced from her first husband, William Stearns, a month before she moved to Montana) arrived in the middle of this great rush to “free land,” recognizing that with a well-chosen site and some luck she might find stability just south of the 49th parallel. With six years of experience with her husband and four children on a Dominion Lands Grant in Saskatchewan, Canada, that ended abruptly in 1911, she had come to recognize what to look for, and hired Glasgow land locator Sidney Rundle to guide her to a good claim.

The original exhibition contains a dynamic gallery for viewing this multi-page document.

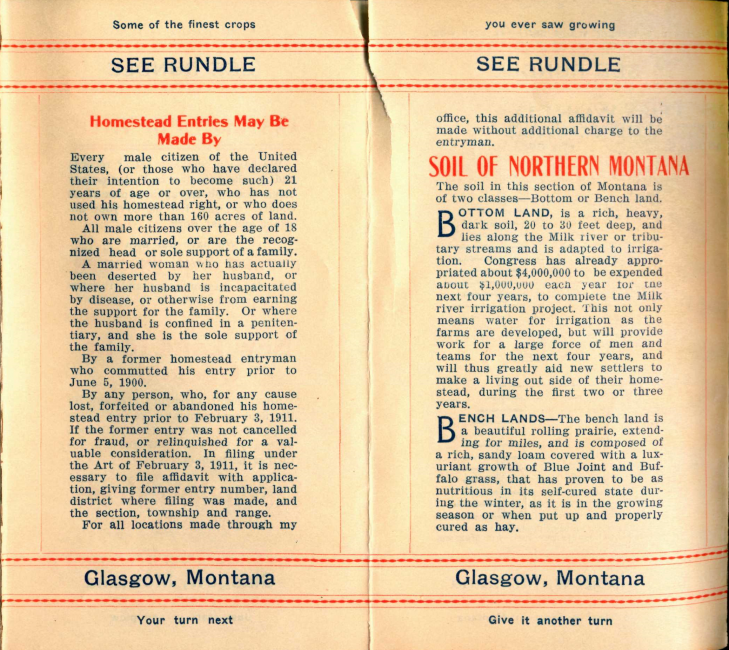

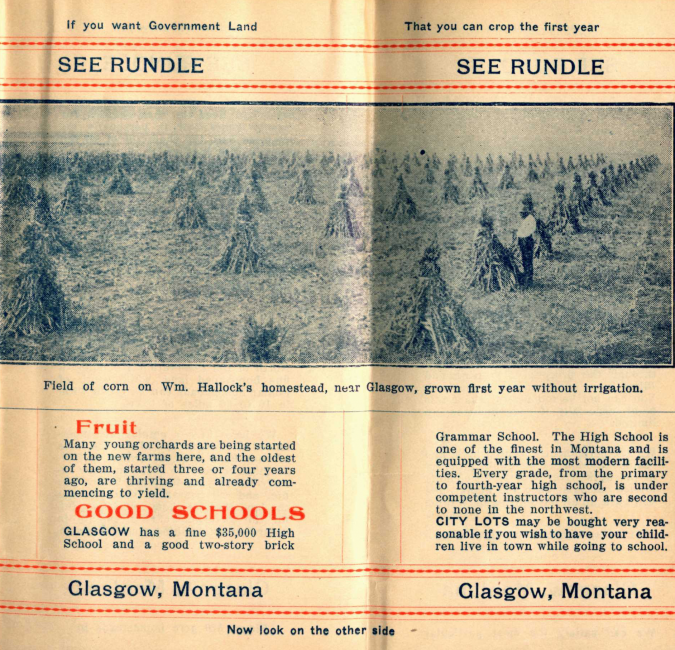

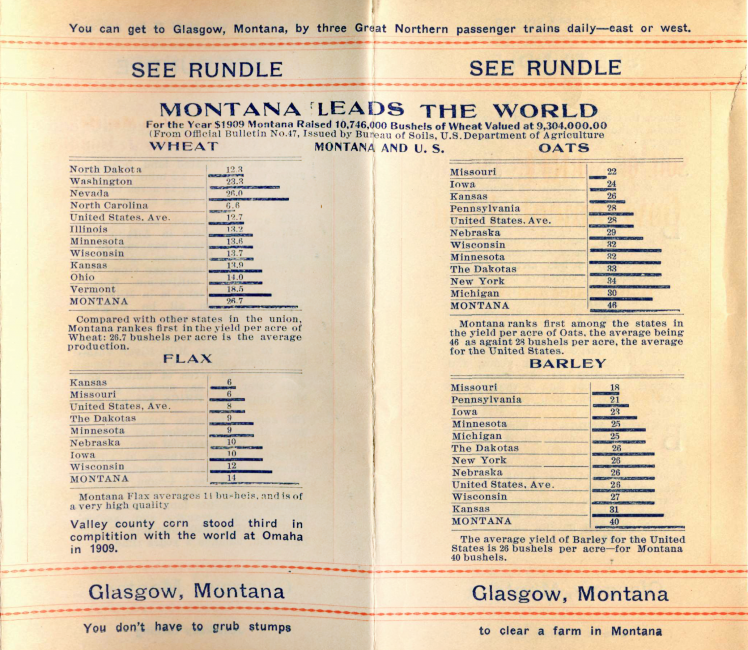

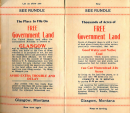

The “See Rundle” three-color brochures celebrated the opportunities abounding on northeastern Montana’s shortgrass plains. The advertisement captures the quirky creativity of this land locator working to capture the attention and the cash of aspiring homesteaders—and the progression of clever inducements merits a closer look: “Come to Glasgow… And we will show you… What other settlers are doing…”

The “See Rundle” brochure

Public domain. Courtesy Wisconsin State Historical Society.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Rundle helped her identify a promising 160-acre parcel that beckoned fourteen miles (22.5 km) northwest of Glasgow, and Stearns filed her first homestead application on 6 December 1912. This land was suited to cultivating small grains and grazing, and prime for capitalizing upon the district’s natural advantages. Water and shelter were crucial in this region, and this quarter-section provided easy access to both: Loamy soils had been deposited by the river over the course of millennia; two springs bubbled within three-quarters of a mile; and the Milk River meandered less than a mile (1.6 km) to the south.

The Milk River abuts Lily Stearns’s second claim, and its reliable flow of water is a central defining feature of the landscape near Glasgow. US explorers Merriweather Lewis and William Clark named the river in 1804, recording in their journals that the distinctive color of the water was noteworthy for its “peculiar whiteness, such as might be produced by a tablespoon of milk in a dish of tea.”

The Milk River abuts Lily Stearns’s second claim, and its reliable flow of water is a central defining feature of the landscape near Glasgow. US explorers Merriweather Lewis and William Clark named the river in 1804, recording in their journals that the distinctive color of the water was noteworthy for its “peculiar whiteness, such as might be produced by a tablespoon of milk in a dish of tea.”

Photograph by Sara Gregg, 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stearns arrived in the middle of a period of generous rainfall and temperate weather, golden years when nodding fields of flax and wheat encouraged the ambitions of eager homesteaders. She embraced the potential embedded within these rolling terraces, explaining in a letter to her church’s newspaper: “I came here believing it was best for me and for my welfare.” There was tremendous promise resting in these rolling grasslands, and she envisioned that it would provide a stable home for her family: the fertile soils would support good crops, while the abundance of cottonwoods along the river would provide “plenty of timber for posts and fencing and fuel.”

The expansive spaces of northeastern Montana, where Stearns homesteaded in 1912, emerge as unmarked territory in this General Railway Map of the United States in 1918. The State of Montana is outlined in red in this map, and Lily’s homestead is marked with a dot.

The expansive spaces of northeastern Montana, where Stearns homesteaded in 1912, emerge as unmarked territory in this General Railway Map of the United States in 1918. The State of Montana is outlined in red in this map, and Lily’s homestead is marked with a dot.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.