Chough’s nest, Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

Chough’s nest, Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

This photo was taken by Lesley Instone, 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Standing on this spot … if I look up I can see a perfect circle silhouetted high up above my head in the branches of a red stringybark tree. If I move around and squint against the light I can see that it’s actually a container sculpted in mud, with a flattish bottom and beautifully finished sides, smooth and sleek. It’s like a large bowl and it’s constructed around an upper branch where it sits snug, shielded from winds and predators.

Standing on this spot … if I look down I can see two round depressions in the ground, both about the same size. They are lined with stone, and have a curious opening on the downhill side. The stone has turned reddish on the inside and they have filled with earth, disguising their original depth.

Quartz kilns, Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

Quartz kilns, Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

Both photos were taken by Lesley Instone, 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

One container high above my head. Two containers at my feet. The one is a chough’s nest built this spring, the two are remnants of quartz kilns dating from the early 1850s gold rushes. This chance mingling and meeting of old and new, nature and culture, embodies the core of this place: once a ravaged gold mining landscape, now the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park. Established in 2002, this is Australia’s first national park with an emphasis on (non-Indigenous) cultural not just natural values. Australia’s national park system evolved from a wilderness model where evidence of settler occupation was often removed to make park landscapes look more natural. In reserving an area of highly modified vegetation and altered landforms, Castlemaine Diggings demonstrates a significant shift towards a more integrated understanding of the inseparability of nature and culture; what Donna Haraway terms naturecultures.

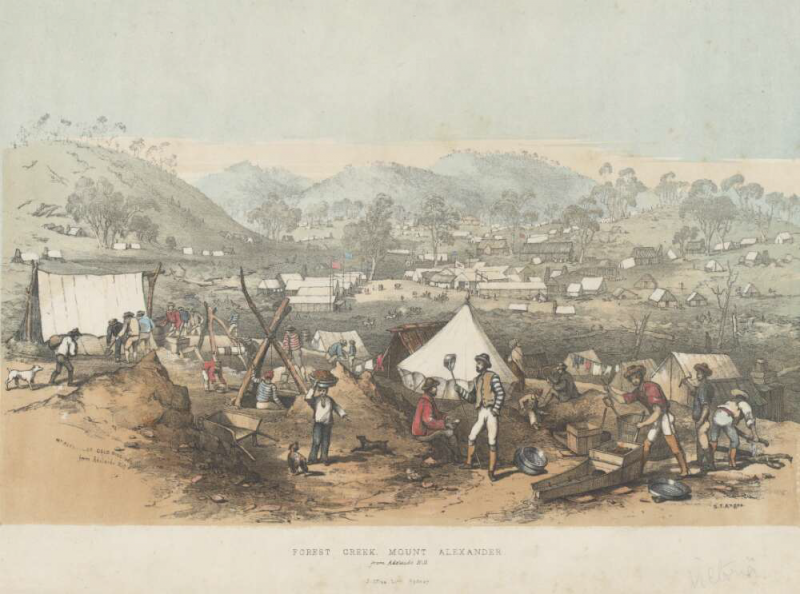

Gold Diggings at Forest Creek, Mount Alexander (1851–52)

Gold Diggings at Forest Creek, Mount Alexander (1851–52)

Ham, Thomas, and David Tulloch. Gold Diggings at Forest Creek, Mt Alexander. 1851-1852. Ham’s five views of the gold fields of Mount Alexander and Ballarat in the colony of Victoria.

Source: State Library of Victoria.

Click here to view State Library of Victoria source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Originally home to the Jaara Jaara people, this area of box-ironbark forest was invaded by Europeans in the 1840s. The squatters set up sheep runs and laid claim to vast tracts of country, with only a scant European population occupying the land. However, when gold was discovered in the Castlemaine region in 1851, a massive influx of people changed the region forever, with at least 40,000 people living on these goldfields by March 1852.

How many ways are there for gold miners to devastate a landscape? Plenty! At first miners scoured surface layers to reveal alluvial gold. Streams were diverted and “turned into heaps of gravel and mud.” The streamside flats were peppered with holes as each team of miners dug a pit on their mining license site covering an area of just 8 to 12 square feet. Water was turned into polluted soupy mud from the many puddling machines and cradles set up near the stream to separate the dirt from the gold nuggets. Some miners soon shifted their attention from alluvial gold to gold found in quartz. They broke off quartz pieces and roasted them in a kiln, like the ones I’m standing next to, so that they could be more easily crushed with hammers to reveal the gold within. Roasting involved layering quartz and wood in the kiln, and then firing, sometimes for a week.

Forest Creek, Mount Alexander, from Adelaide Hill (1852)

Forest Creek, Mount Alexander, from Adelaide Hill (1852)

Allan, John, and George French Angas. Forest Creek, Mount Alexander, from Adelaide Hill. 1852.

Source: National Library of Australia, NLA Call No: PIC Solander Box C15 #U76 NK6288/B.

Click here to view National Library of Australia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Later, post-1850s phases of mining, which continued into the 1990s in some areas, brought industrial-scale devastation to the goldfields, a devastation whose impacts are layered on top of those from the 1850s. These include a widespread network of water races, ground sluicing, hydraulic sluicing and dredging, dams, stamper batteries, mills, and pits from deep lead mining. The intensity of these practices has created a distinctive landscape of pre-mining features overlapping and interlaced with pits and depressions, abundant mullock heaps, disrupted water courses, extensive erosion, soil-less areas, denuded zones, stunted forests, and the ruins of mining and domestic buildings.

The multiple temporalities of nest and kilns bring into sharp relief the continuing entanglement of the 1850s gold rushes with the here and now of this park. Despite the destruction and changes, human and nonhuman life asserts itself in new and continuing forms. Indeed, one of the key values given as a reason for listing the park was the resilience of its natural features in the face of change. Where I’m standing looking at the nest and the kilns, I’m surrounded by a coppice forest of box trees, red stringybark, and a few ironbark trees, with fields of wildflowers mixed with introduced grasses. This is a forest quite unlike the box-ironbark forest of the Jaara Jaara that the first gold diggers would have encountered. However, this blended forest continues to support a rich array of plants and animals along with a range of threatened flora, fauna, and ecological communities. It also supports changing human relations with the ongoing recognition of Indigenous rights, obligations, and knowledge in park management.

Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

This photo was taken by Lesley Instone, 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Just as the Jaara Jaara shaped the pre-colonial forests, today’s forest is a historical artefact of the gold rushes. Today’s visitors to the park encounter a multilayered, multi-temporal landscape that continues to morph and evolve in relation to contemporary park management practices. Castlemaine Diggings is neither wilderness nor rewilding, but an alter-story that refuses modernist oppositions and purified landscapes. Once devastated, now recuperating, albeit in novel forms, this is a site of emerging environmental histories of post-colonizing, post-mining lands where new naturecultures are being actively generated.

How to cite

Instone, Lesley. “A Post-Wilderness National Park: Naturecultures of Destruction and Recuperation in the Castlemaine Goldfields.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2017), no. 17. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7920.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2017 Lesley Instone

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Annear, Robyn. Nothing but Gold: The Diggers of 1852. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2012.

- Finlay, Alexander. Goldrush: The Journal of Alexander Finlay While at the Victorian Gold Diggings, May 1852. Sydney: St Marks Press, 1992.

- Frost, Warwick. “Visitor Interpretation of the Environmental Impacts of the Gold Rushes at the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park.” In Mining Heritage and Tourism: A Global Synthesis, edited by Michael V. Conlin and Lee Joliffe, 97–107. Milton Park UK: Routledge, 2010.

- Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

- Hobbs, R. J., B. A. Harvie, and C. M. Hall. Novel Ecosystems: Intervening in the New Ecological World Order. Chichester UK: Wiley‐ Blackwell, 2013.

- Jørgensen, Dolly. "Rethinking rewilding." Geoforum 65 (2015): 482–488.

- Low, Tim. The New Nature: Winners & Losers in Wild Australia. Melbourne: Viking, 2002.