A stranger viewing our land from above and seeing nothing but mountains and hills covered with forests would scarcely be able to believe that there is a shortage of wood here. But if the stranger were to descend into the woods, he would immediately recognize the contradiction between the way wood is wasted on the one hand, while at the same time forest management is neglected. — Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner, Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen (“Essays and Observations”), 1768

Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner (1699–1777) opened his article with an effective rhetorical strategy, using the perspective of a stranger to diagnose the situation in the Bern forests.

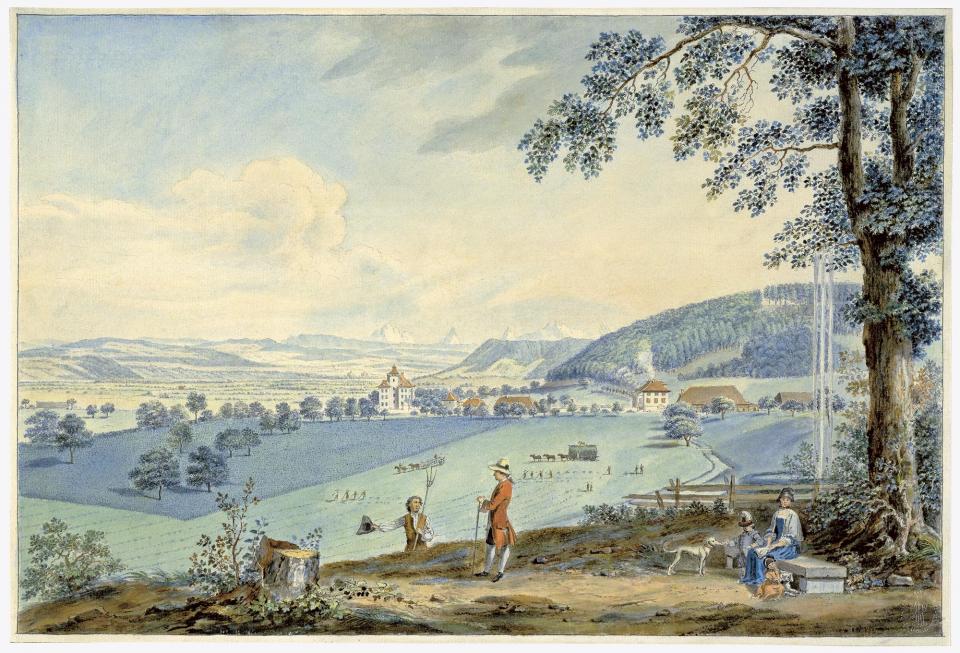

Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner, founding member, secretary, and later president of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern on his estate “Blumenhof” talking with a peasant.

Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner, founding member, secretary, and later president of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern on his estate “Blumenhof” talking with a peasant.

Watercolor by J. J. Aberli, 1775

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

His diagnosis was based on international forestry literature as well as on extensive practical experience. In 1752 he took on the management of the estate Blumenhof in Kehrsatz, which included 50 acres of forest. In 1764 Tscharner was elected as a member of the official forestry department (Holzkammer) and served as an inspector in the Königsberg Forest. When the forestry department commissioned wood shipments along the Aare River from the uplands to Bern, Tscharner negotiated prices with the contractor. Finally, he was deeply involved with the forest management in the district of Schenkenberg, which he presided over as bailiff starting in 1767.

First, Tscharner proposed political reform of the forest management. He complained that the peasants in his district of Schenkenberg had no scruples about breaking forest use regulations. Therefore it was necessary to pay forest rangers (Bannwarte) well, since otherwise only the poorest people in the village would willingly take on the job, often themselves participating in law-breaking. At higher levels of the forestry administration, he called for better professional qualifications. A forester should be well-informed about the various kinds of forests and trees in his precinct. He and his assistants (Unterförster) should be able to describe exactly how many trees had been planted and harvested. This goal of equilibrium was implicitly based on the principle of sustainability. This principle also guided Tscharner’s explicit call to think of the future as well as the present.

In addition, Tscharner’s plan included directions for how foresters could increase production. None of the standard German texts on the topic offered any instructions suitable for the rural Bern population, he maintained. All were either too elaborate or too academic or not applicable to the situation in Bern. Therefore Tscharner included in his article a forestry calendar which clearly and concisely presented the various forestry activities, broken down month-by-month.

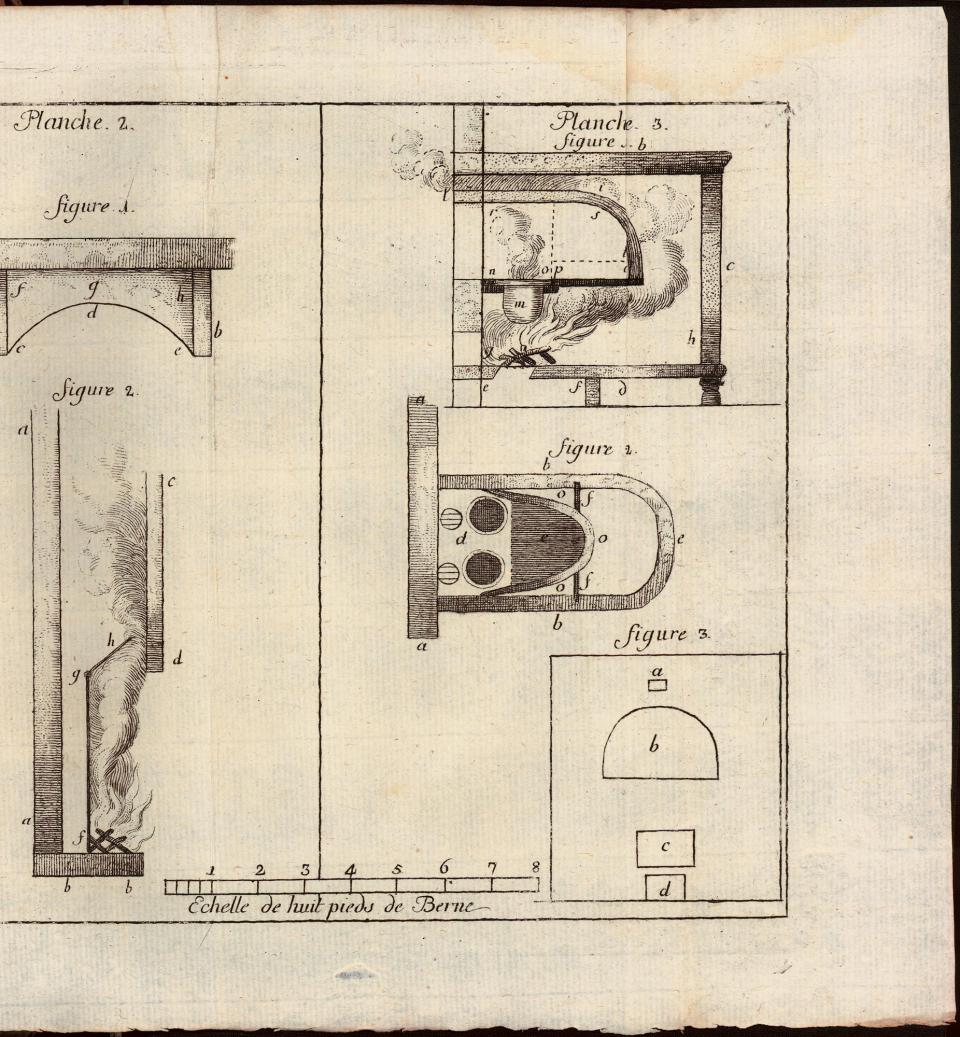

Finally, Tscharner addressed wood consumption. There was a high degree of waste resulting from the surplus of wood available in the past, which led previous generations to develop an ever-increasing inclination for luxury and comfort. In order to counter this, Tscharner called for more thriftiness. The Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern had created a whole set of methods to encourage this: they called for the use of more efficient stoves in living rooms instead of the open fireplaces which had become popular. Bricks were to be used instead of wooden shingles, hedges instead of wooden fences, and coal instead of firewood.

Sketch of a combined kitchen and sitting-room oven used to save energy

Sketch of a combined kitchen and sitting-room oven used to save energy

Source: Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen der Oekonomischen Gesellschaft Bern 1768, 1. Stück.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Pine tree by Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (1755). Duhamel du Monceau’s work was an important basis for Tscharner’s ideas.

Pine tree by Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (1755). Duhamel du Monceau’s work was an important basis for Tscharner’s ideas.

Source: Duhamel du Monceau, Henri-Louis. Traité des arbres et arbustes, Paris, 1755, p. 121.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

How much the comprehensive renewal programs actually changed the Bern forests is a question that remains to be researched. On the one hand, the modernizers of the forest were able to guide wood supply and delivery in their roles as bailiffs and members of the forestry department. The influence of the Economic Society was evident in the Bern forest law of 1786. On the other hand, at the administrative level it was not possible to implement the key elements of the modernization program. The additional forester positions never materialized, nor was there any binding agreement to raise the pay of the forest rangers.

How to cite

Stuber, Martin. “Political Reform, Professional Knowledge and Moral Appeals: Tscharner’s Strategy for Sustainability.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5049.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2013 Martin Stuber

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Radkau, Joachim. “Das ‘hölzerne Zeitalter’ und der deutsche Sonderweg in der Forsttechnik.” In ‘Nützliche Künste’: Kultur- und Sozialgeschiche der Technik im 18. Jahrhundert, edited by Ulrich Troitzsch, 97–117. Münster: Waxmann, 1999.

- Stuber, Martin. Wälder für Generationen: Konzeptionen der Nachhaltigkeit im Kanton Bern (1750–1880). Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2008.

- Stuber, Martin. “Niklaus Emanuel Tscharners ‘Anweisung zu der besten Oekonomie der Wälder.’” In Kartoffeln, Klee und kluge Köpfe: Die Oekonomische und Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft des Kantons Bern OGG (1759–2009). Edited by Martin Stuber, Peter Moser, Gerrendina Gerber-Visser, and Christian Pfister, 99–104. Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2009.

- Tscharner, Niklaus Emanuel. "Anweisung für das Landvolk zu der besten Oekonomie der Wälder", in: Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen durch die oekonomische Gesellschaft. Bern, 1768. (2. Stück): 1–63.

- Wälchli, Karl. Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner: Ein Berner Magistrat und ökonomischer Patriot 1727–1794. Bern: Stämpfli & Cie, 1964.