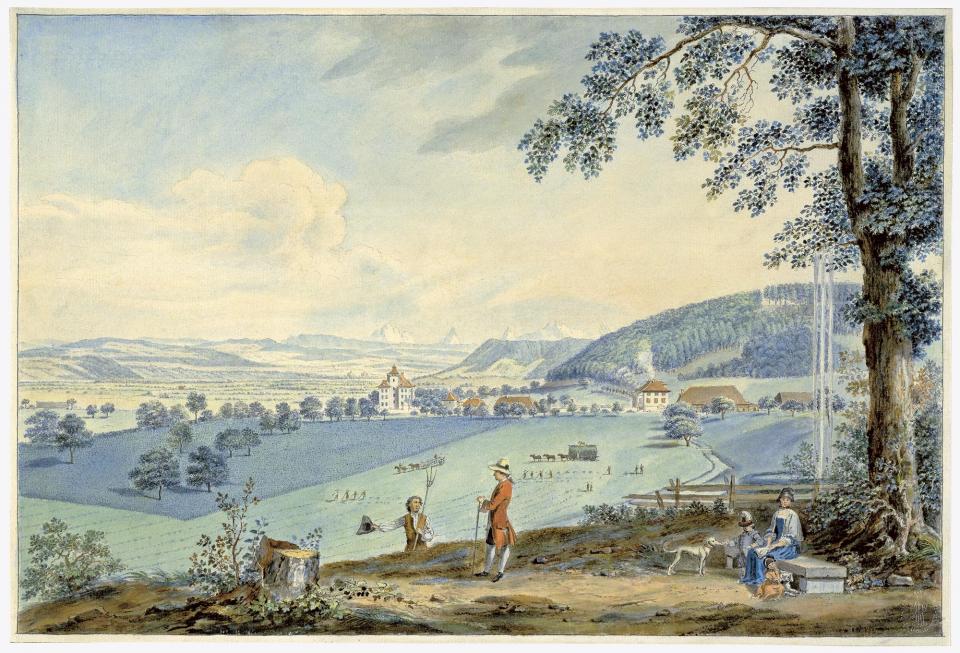

Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner, founding member, secretary, and later president of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern on his estate “Blumenhof” talking with a peasant.

Niklaus Emanuel Tscharner, founding member, secretary, and later president of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern on his estate “Blumenhof” talking with a peasant.

Watercolor by J. J. Aberli, 1775

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Agriculture was the primary focus of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft’s initial program in 1759, although it was not the only concern. Wetlands were to be drained, rivers were to be made more easily navigable and the riverbeds reinforced, and the earth was to be investigated for useful materials such as fertilizers, fuel, and metals. The organization aimed to promote manufacturing and reduce energy consumption. The overall goal was to create an industrious, prosperous, and contented population. This broad approach had its basis in the traditional European household economy, but at the same time went considerably beyond it. The static perspective of the “Hausväter” was replaced by a dynamic, growth-oriented model, and the scope was extended from the individual household to the entire territory.

The Oekonomische Gesellschaft was dominated by educated magistrates, with nearly two-thirds of the 126 official members in 1800 being Bern patricians, who could thus act both as scientific and technical experts, as well as political reformers. A second important group consisted of clergymen, who were the most active participants among the 228 members of the branches of the society distributed throughout the entire territory. Honorary members, 192 in all, from Switzerland, Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, and Russia formed a third group and provided international exchange of ideas as well as securing the Bern society’s international reputation.

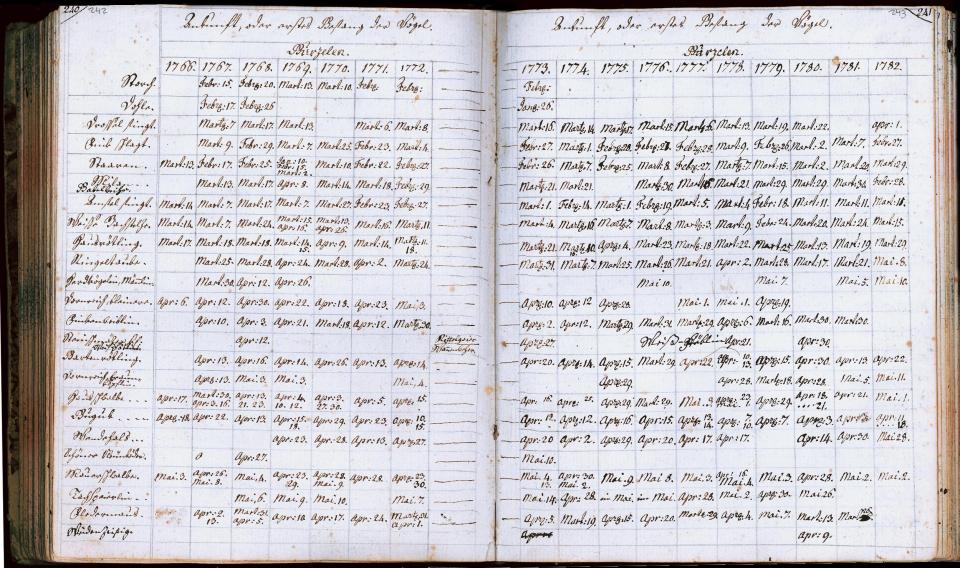

The far-reaching goals were put into action at various levels. The initial starting point was a surveying project. The Oekonomische Gesellschaft organized an ongoing and standardized meteorological measurement system, produced a comprehensive inventory of botanical resources, and wrote “Topographical and Historical Descriptions” of the region’s potential for development.

Secondly, the Bern society was part of a continuous international dialogue: it maintained a network of correspondence, exchanging practical experiences and scientific literature as well as textile samples and cultivated plant varieties.

Types of barley for sowing (1782)

Types of barley for sowing (1782)

von Haller, Albrecht. “Arten und Spielarten des Getreides,” in Neue Sammlung physisch-oekonomischer Schriften, Bern: Oekonomischen Gesellschaft, 1782.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

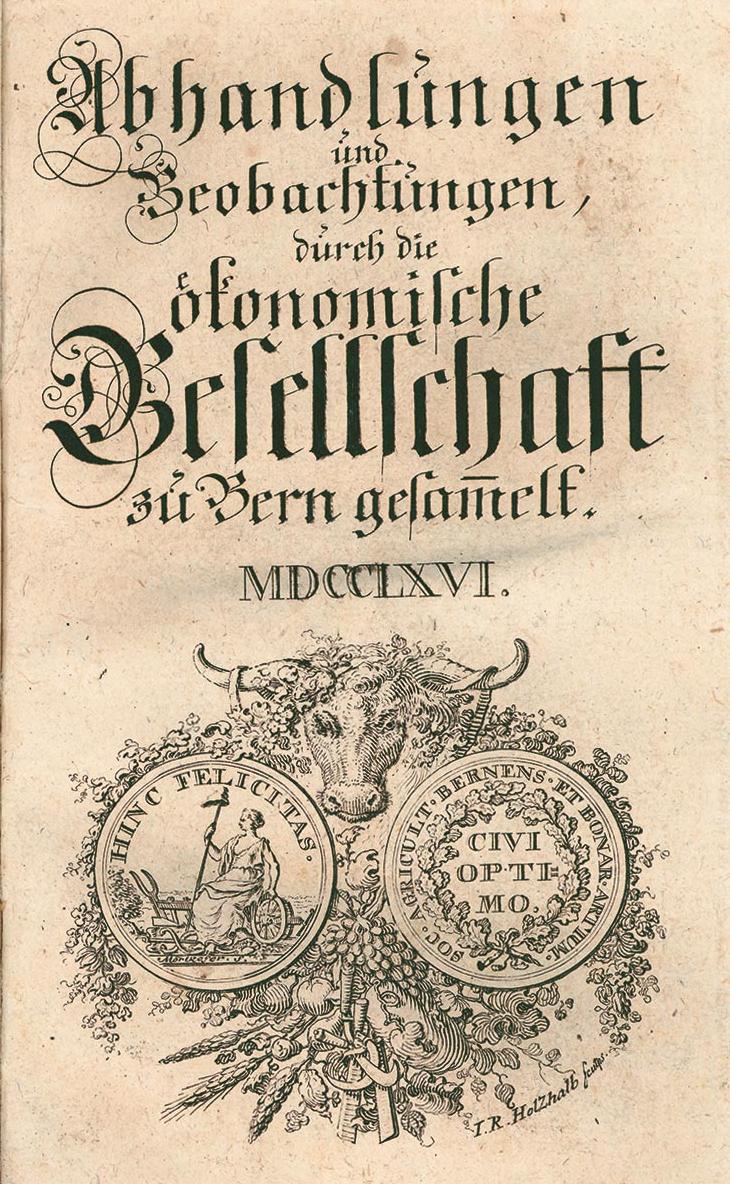

The Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen (“Essays and Observations”) of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft were published simultaneously in German and French, which was crucial for strengthening the international connections of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft.

The Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen (“Essays and Observations”) of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft were published simultaneously in German and French, which was crucial for strengthening the international connections of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft.

Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen durch die Ökonomische Gesellschaft zu Bern gesammelt. Bern: Ökonomische Gesellschaft zu Bern, 1779-1782.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Thirdly, the Oekonomische Gesellschaft sought public awareness and involvement: it advertised essay contests with prizes, offered rewards for innovative practical accomplishments, and published an internationally respected journal, Abhandlungen und Beobachtungen (“Essays and Observations”). Finally, it worked to implement its reform proposals both in society and government administration.

As was the case for the Economic Enlightenment in many places, there was a discrepancy between the ambitious goals of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft and the limited implementation of them in reality. However, economic-patriotic societies cannot be measured simply on the basis of their immediate practical effects. A longue durée perspective is more useful. The efforts to modernize the (agricultural) economy and the (agricultural) landscape, as well as institutional, experimental, discursive, and media aspects of the Economic Enlightenment continue well into the nineteenth century, when they first truly begin to develop. This can be seen particularly clearly in the example of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern, which transformed itself from an elite reform society in the eighteenth century into an agricultural association with a wide social base in the nineteenth century, and thereby continued to play an important and more-or-less uninterrupted role in the active development of a more scientifically based use of nature.

How to cite

Stuber, Martin. “Foundation of the Oekonomische Gesellschaft Bern.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5005.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2013 Martin Stuber

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Gerber-Visser, Gerrendina. Die Ressourcen des Landes: Der ökonomisch-patriotische Blick in den Topographischen Beschreibungen der Oekonomischen Gesellschaft Bern (1759–1855). Baden: Hier + Jetzt, 2012.

- Holenstein, André, Martin Stuber, and Gerrendina Gerber-Visser, eds. Nützliche Wissenschaft und Ökonomie im Ancien Régime: Akteure, Themen, Kommunikationsformen. Cardanus Jahrbuch für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Vol. 7. Heidelberg: Palatina, 2007.

- Popplow, Marcus, ed. Landschaften agrarisch-ökonomischen Wissens: Strategien innovativer Ressourcennutzung in Zeitschriften und Sozietäten des 18. Jahrhunderts. Münster: Waxmann, 2010.

- Salzmann, Daniel. Dynamik und Krise des ökonomischen Patriotismus: Das Tätigkeitsprofil der Oekonomischen Gesellschaft Bern 1759–1797. Nordhausen: Traugott Bautz, 2009.

- Stuber, Martin. “Kulturpflanzentransfer im Netz der Oekonomischen Gesellschaft Bern.” In Wissen im Netz: Botanik und Pflanzentransfer in europäischen Korrespondenznetzen des 18. Jahrhunderts, edited by Regina Dauser et al., 229–69. Berlin: Akademieverlag, 2008.

- Stuber, Martin, Peter Moser, Gerrendina Gerber-Visser, Christian Pfister et al., eds. Kartoffeln, Klee und kluge Köpfe: Die Oekonomische und Gemeinnützige Gesellschaft des Kantons Bern OGG (1759–2009). Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2009.

- Wyss, Regula, and Martin Stuber. “Paternalism and Agricultural Reform: The Economic Society of Bern in the Eighteenth-Century.” In The Rise of Economic Societies in the Eighteenth Century: Patriotic Reform in Europe and North America, edited by Koen Stapelbroek and Jani Marjane, 157–81. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.