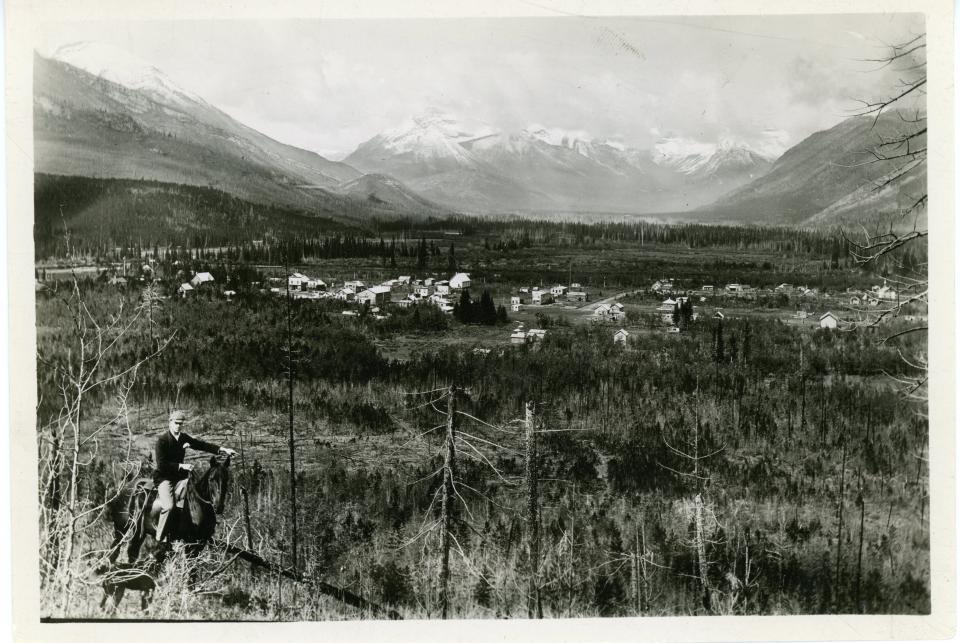

Banff town site, 1889 or 1890

Banff town site, 1889 or 1890

Source: Second Century Club collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1887, during debate on the bill to create Canada’s first national park, Senator John Abbott explained why the park’s proposed name, “Banff,” simply would not do. Already the name of the small town at the heart of the park in the Rocky Mountains of Alberta, it was tribute to a Scottish locale. But according to Abbott, Banff was also a word “which is sometimes substituted for a still warmer climate… [I]t is not uncommon in Scotland in the heat of discussion to consign a man to ‘Banff’…” Banff was hell. The government chose to christen the protected area Rocky Mountains Park. But the park remained so associated with the town that it was commonly referred to as Banff National Park, and in 1930 it took that name officially.

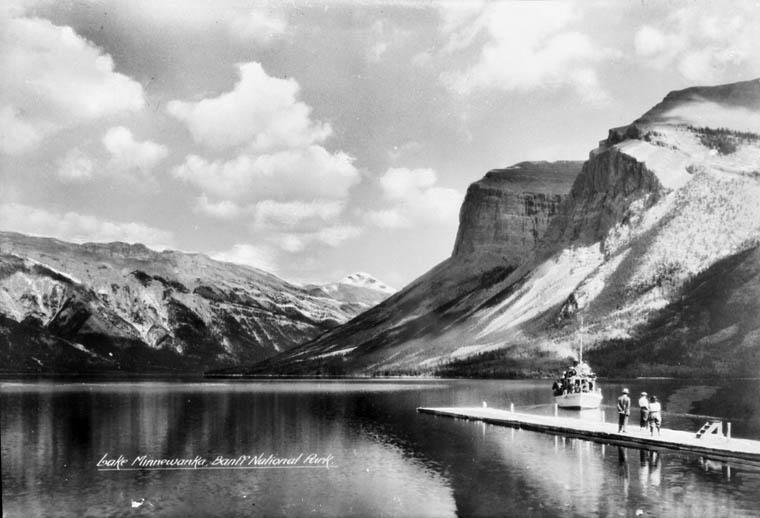

Lake Minnewanka, Banff National Park, Alberta, ca. 1900-1925

Lake Minnewanka, Banff National Park, Alberta, ca. 1900-1925

Credit: Albertype Company. Library and Archives Canada, PA-032771.

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Lake Minnewanka, Banff National Park, Alberta, 2012

Lake Minnewanka, Banff National Park, Alberta, 2012

Photo taken by Alan MacEachern.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Banff is the Canadian national park most people have heard of. It was the nation’s first and has always been its most visited and most famous. Everyone from Arthur Conan Doyle to Marilyn Monroe to Mikhail Gorbachev has toured it. Frank Lloyd Wright built a pavilion there. It was at Banff Indian Days that a Nazi fugitive was captured in the classic British wartime film The 49th Parallel. Today, Banff is one of forty parks and reserves in Canada’s national system, but it sees a full 25% of the system’s visitors; its attendance is one of the largest of any national park in the world.

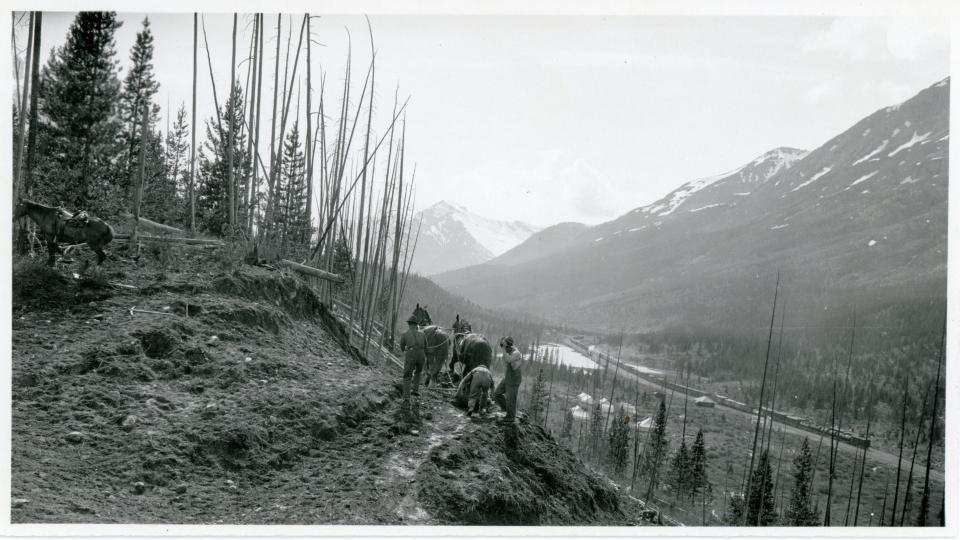

Road building in Banff, 1925

Road building in Banff, 1925

Source: Second Century Club collection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

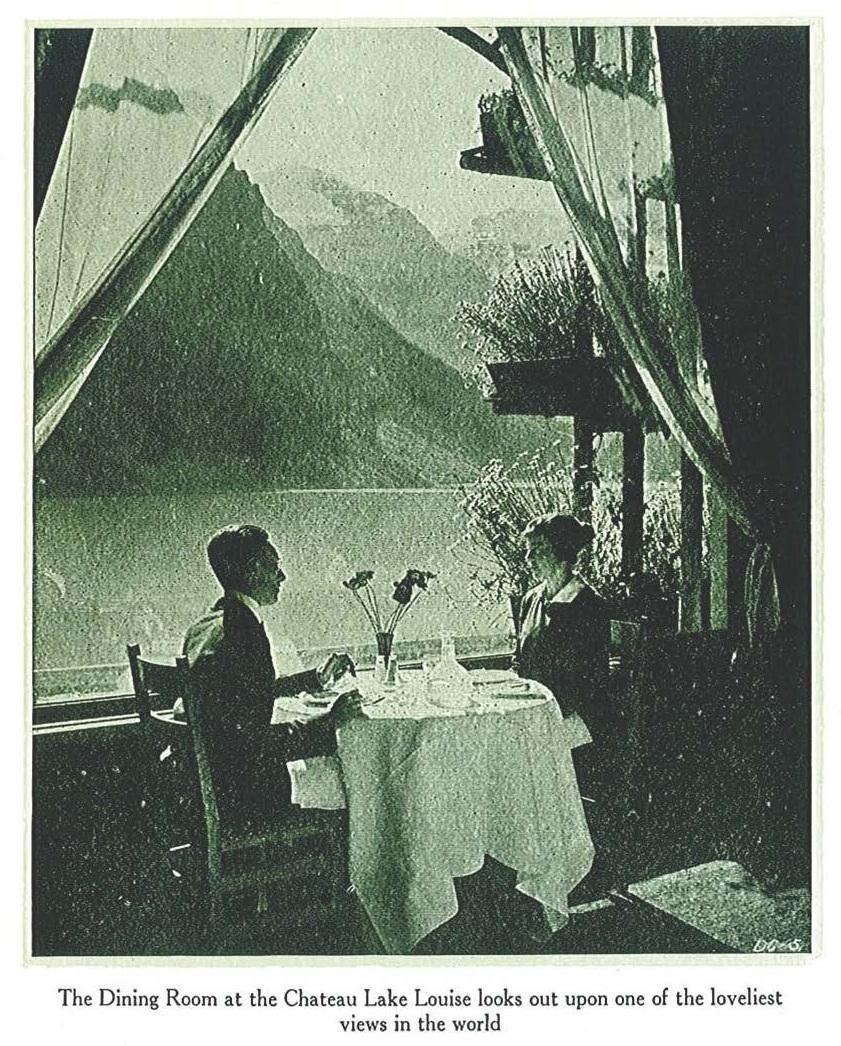

A page in the guidebook The Banff-Windermere Highway, 1924

A page in the guidebook The Banff-Windermere Highway, 1924

Williams, M.B. The Banff-Windermere Highway, 1924. Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1924.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Banff Springs Hotel today

The Banff Springs Hotel today

Click here to view Pixabay source.

This work is licensed as a Public Domain Dedication.

All this attention for more than 125 years has had its impact. The area’s aboriginal people, the Stoney, were pushed out when the park was created. The town, the trails, and the Trans-Canada Highway that was allowed to slice through the park—all experience traffic congestion. A subspecies of fish, the Banff longnose dace, was driven to extinction thanks to habitat destruction. Banff was where Parks Canada first developed—that is, experimented on—many of its policies related to wildlife, fire, town site planning, and tourism development. So, for example, the agency introduced elk, a non-indigenous species, from Yellowstone in the late 1910s, and by the late 1930s the animals’ population explosion convinced wardens to implement annual slaughters. Historically, Parks Canada did not just tolerate the park’s all-out development, but led the way: in the 1930s, its new golf course, a huge engineering project, was believed to be the most expensive ever constructed; in the 1960s, responding to a craze for skiing, it swiftly built up three ski resorts which led to three (failed) Winter Olympics bids. The amount of development at Banff has in recent times threatened the park’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“Fire auto”, Banff Warden C.V. Phillips and Chief Warden Howard Sibbald, ca. 1923

“Fire auto”, Banff Warden C.V. Phillips and Chief Warden Howard Sibbald, ca. 1923

Source: Second Century Club collection

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

And yet, Banff is not hell. The philosophy that originally led to places being set aside as outstanding examples of a nation’s natural beauty—the philosophy that led people to flood into places such as Banff—has also led people, including the places’ caretakers, to recognize that the needs of the place must have primacy. As active as Banff National Park has been in terms of development, it has in recent decades also become active in maintaining ecological integrity. It has been an international leader in using fire to restore forest ecosystems. The local wolf population, extirpated in the mid-twentieth century, is now recovering, and there is work underway to reintroduce the bison. Wildlife corridors and highway overpasses have been built to allow for better movement of populations. The Banff-Bow Valley Study, a public inquiry in the 1990s, confirmed ecological protection to be the prime purpose of the park—which, as always when Banff is involved, had repercussions throughout the entire Canadian national parks system.

The spotlight of attention that Banff National Park receives ensures it will continue to be a site of intense human use and intense protection. Not heaven, but not hell either, Banff exemplifies the contradictions inherent in maintaining inviolable a place for people, the contradiction at the heart of the national park idea.

Peyto Lake, one of the attractions located in Banff National Park

Peyto Lake, one of the attractions located in Banff National Park

Photo taken by Tobias Alt.

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

How to cite

MacEachern, Alan. “Banff Is … Hell? The Struggle of Being Canada’s First, Most Famous, and Most Visited National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2016), no. 10. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7623.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2016 Alan MacEachern

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Armstrong, Christopher, and H.V. Nelles. Wilderness and Waterpower: How Banff National Park Became a Hydroelectric Storage Reservoir. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2013.

- Binnema, Theodore, and Melanie Niemi. “‘Let the Line be Drawn Now’: Wilderness, Conservation, and the Exclusion of Aboriginal People from Banff National Park in Canada.” Environmental History 11 (2006): 724–50.

- Campbell, Claire, ed. A Century of Parks Canada, 1911–2011. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2011.

- Hart, E.J. (Ted). J.B. Harkin Father of Canada’s National Parks. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2010.

- Hodgins, Douglas W., and J. Douglas Cook. The Banff-Bow Valley Study: A Retrospective Review. Parks Canada Occasional Papers 10, 2000.

- Kopas, Paul. Taking the Air: Ideas and Change in Canada’s National Parks. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007.

- White, Cliff, and E.J. (Ted) Hart. The Lens of Time: A Repeat Photography of Landscape Change in the Canadian Rockies. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2007.