Population growth, natural resource consumption, and an increasing demand for energy were issues that continually and substantially shaped the course of the twentieth century. New innovations in transportation and the expansion of electricity networks throughout the industrialized world required new approaches to solving the energy problem. In the spring of 1928 the Munich architect Hermann Sörgel (1885–1952) presented an idea which promised to solve all these difficulties: Atlantropa offered an “inexhaustible” source of energy, vast quantities of raw materials and new “Lebensraum” for innumerable people.

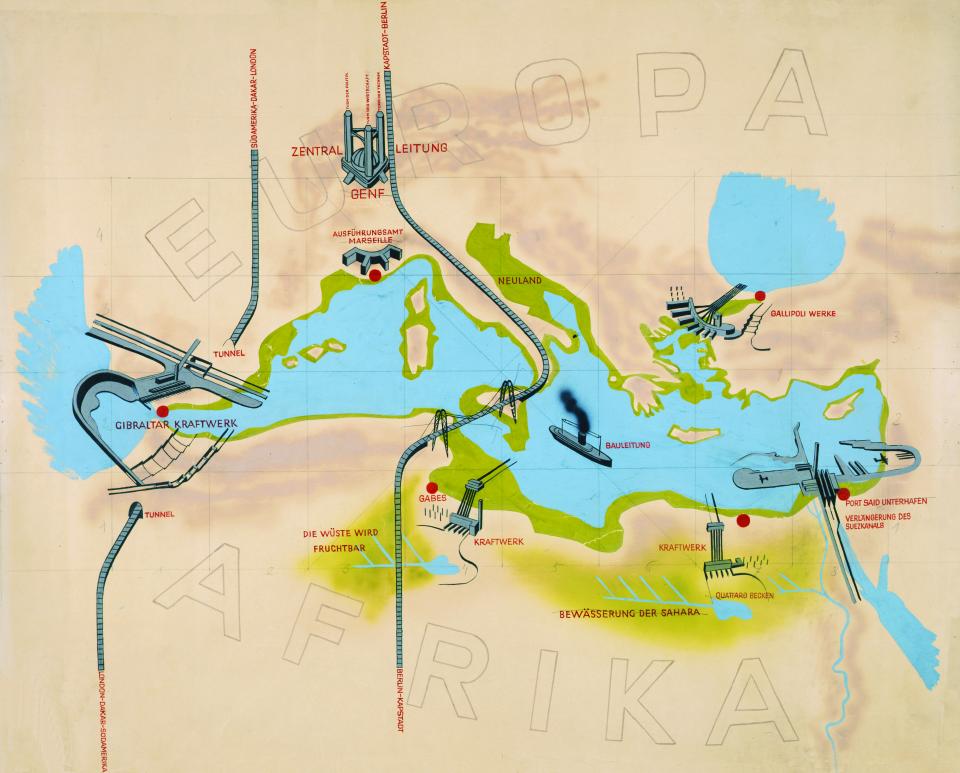

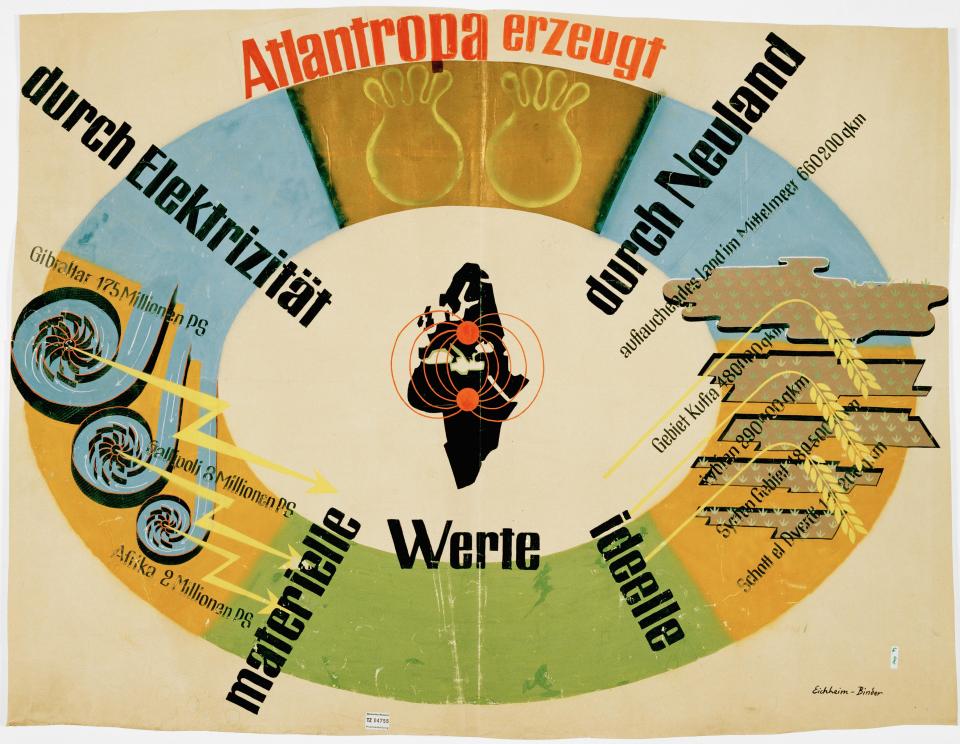

Atlantropa united a technological utopia with political visions of reform. Sörgel proposed building a giant dam across the Strait of Gibraltar to create the largest hydroelectric facility in the world. It would provide for half of Europe’s electricity needs. At the same time, it would cut off the main water supply to the Mediterranean. Evaporation would lead to a drop in the sea level of up to 200 meters and would create new stretches of land along the coast as well as connecting Europe to Africa by land. The two continents would merge into a single entity. This newly-won mass of land would be used for agriculture, extending infrastructure, and as a site for entire cities.

The consequence of this, admittedly, would have been the destruction of the Mediterranean through salinization. However, the vision of creating Atlantropa did not fail due to concerns about ecological damage; this factor hardly came up in discussions of the project. Rather, it was political reasons that were decisive in the end. The project was not feasible either during the Nazi regime or in the post-war period. In addition, it was replaced by the promise of a new solution to the energy problem: Atomic energy became the new symbol of the belief in progress and the need for an unlimited supply of energy. In 1986, however, the reactor accident at Chernobyl would greatly unsettle this trust in nuclear power. Hermann Sörgel did not experience all this for himself. He died on 25 December 1952 as the result of an auto accident, and his project did not long survive him. The Atlantropa Institute, an association of the sponsors and supporters of the project, disbanded in 1960. Atlantropa was a thing of the past.

In retrospect, Atlantropa was by no means an isolated phenomenon, but rather was one of a whole series of large-scale technological proposals to solve the energy problem. Today, too, new gigantic energy projects are underway around the world, projects such as the Three Gorges Dam in China or the Itaipu Dam in South America, and their consequences for humans and nature cannot be foreseen.

How to cite

Mauch, Felix. “Atlantropa – Endless Energy from the Mediterranean Sea.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2012), no. 9. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/3864.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2012 Felix Mauch

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Gall, Alexander. "Atlantropa: A Technological Vision of a United Europe." In Networking Europe: Transnational Infrastructures and the Shaping of Europe, 1850–2000, edited by Erik van der Vleutena, and Arne Kaijser, 99–128. Sagamore Beach: Science History Publications, 2006.

- Laak, Dirk van. Weiße Elefanten: Anspruch und Scheitern technischer Großprojekte im 20. Jahrhundert. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1999.

- Smil, Vaclav. Energy at the Crossroads: Global Perspectives and Uncertainties. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

- Sörgel, Hermann. Atlantropa. Zurich: Fretz & Wasmuth, 1932.

- Sörgel, Hermann. Die drei großen "A": Großdeutschland und italienisches Imperium, die Pfeiler Atlantropas [Amerika, Atlantropa, Asien]. Munich: Piloty & Loehle, 1938.

- Voigt, Wolfgang. Atlantropa: Weltbauen am Mittelmeer. Ein Architektentraum der Moderne. Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz, 1998.