The Guardian has labeled Agbogbloshie the world’s largest e-waste dump and the largest dump for Western e-waste; the Blacksmith Institute in New York called it one of the most polluted sites on earth. According to Chama and colleagues from the University of Ghana, up to 280,000 tonnes of electrical and electronic equipment from Western countries reach Ghana every year, 75 percent of which is unusable. Some of it gets repaired and re-used, but it sooner or later reaches the dump site in Agbogbloshie, where metals are recovered by informal processes such as burning or leaching. The effects on the health of local people and the environment are tremendous. The e-waste issue has been thoroughly discussed in many venues, from mass media to academia. However, Agbogbloshie consists of far more than just electronic waste.

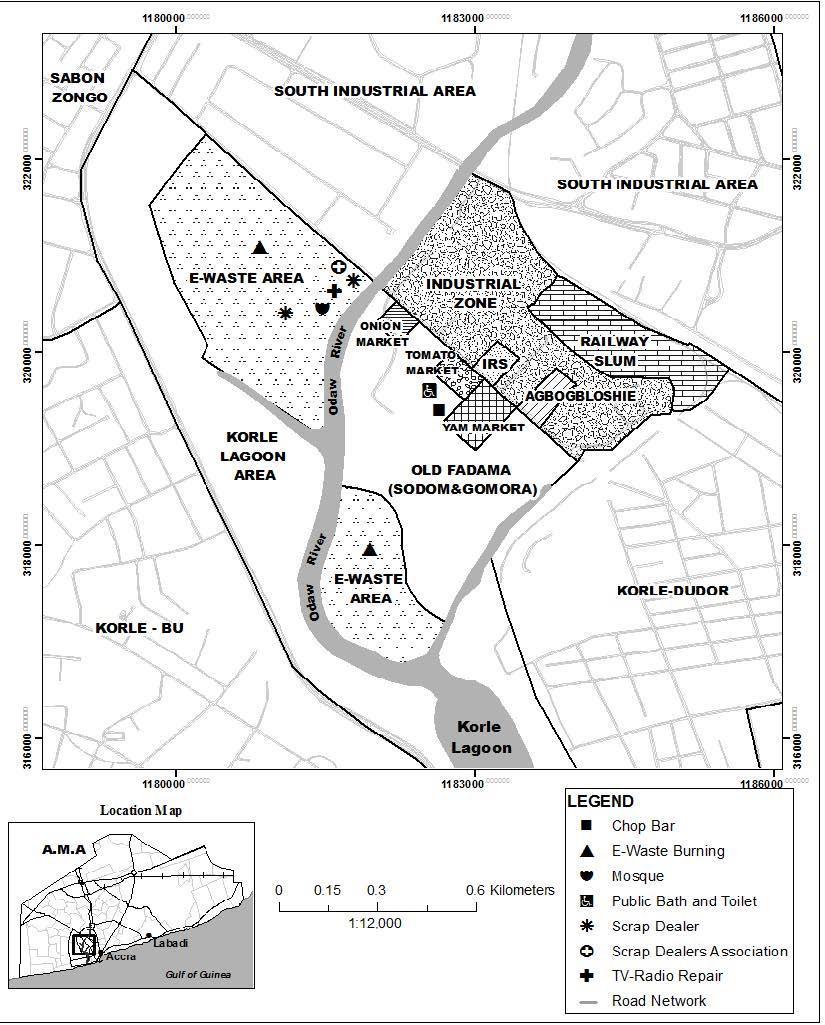

Map of Agbogbloshie.

Map of Agbogbloshie.

Cartography extracted from Martin Oteng-Ababio, “Electronic Waste Management in Ghana - Issues and Practices.” In Sustainable Development - Authoritative and Leading Edge Content for Environmental Management, edited by Sime Curkovic. InTech, 2012.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Agbogbloshie is not a dump site isolated in the countryside, but rather a centrally located neighborhood within the ring road encompassing the inner city areas of Accra, the country’s capital. Two of the most important transport hubs in Ghana, the Kaneshie bus station and the Accra railway station, are less than 500 meters away. Agbogbloshie spans about 7 square kilometers and can be divided into several distinct areas: a settlement, a market, recycling grounds, and dump grounds. A large volume of the material in the dump consists of mixed municipal solid waste arising in Agbogbloshie itself.

Cattle feeding among the waste dumped at Agbogbloshie.

Cattle feeding among the waste dumped at Agbogbloshie.

Photo: Oliver Schwab, June 2015

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The lively market is an important transnational trading center and widely known as a major trading hub for onions. Products such as palm oil soap are manufactured at the site. However, most families in Agbogbloshie make their living from informal recycling. This includes recycling of electrical and electronic equipment, but also of other residual materials such as metal scraps. Recycling can be economically attractive, since the average salary in 2014 in Accra was between 1,000 and 2,000 Ghanian cedis (₵) per month (€1 equals about ₵4) and the metal prices were approximately ₵5,000 per tonne of steel or up to ₵10,000 per tonne of copper.

In particular, considerable numbers of steel-belted tires (tires with steel net inlays for performance improvement) are burned to scavenge the steel, often by using flammable fluids available on-site.

A family with two school-aged children in Accra needed about ₵1,500 a month in 2014 to make a decent living, although many families lived on far less than that, especially in neighborhoods like Agbogbloshie. Assuming an average tire weight of 12 kg, an average steel content of 10 percent by mass and a recovery rate of 100 percent with an appropriate steel quality, 250 tires would need to be burned per month to sustain a family on a decent level.

Although the environmental and health impacts have been frequently discussed and analyzed, the social situation is often put second place. With a high proportion of poor and socially disadvantaged residents, Agbogbloshie is notorious for its high crime rate (it is nicknamed “Sodom and Gomorrah” by locals). Most people come from rural areas, often from the very north of Ghana, in search of a future in the urban agglomeration of Accra. Many get stuck in Agbogbloshie. In June 2015, a neighborhood in “Sodom and Gomorrah” was cleared by the municipality as a political reaction to the so-called 3 June disaster (reported for example in the Daily Graphic, a major Ghanian newspaper), when several hundred people died as the result of a flood and fire. The city responded to demonstrations, an aggressive atmosphere, and acts of violence by the now-homeless and frustrated inhabitants by sending a massive police presence equipped with armored vehicles and automatic weapons. Agbogbloshie is probably as much a social tragedy as it is an environmental one and it is important to examine to what degree the situation is a consequence of the prior social structure and to what extent it is influenced by the informal recycling sector. Labeling Agbogbloshie a “dump site” also does not seem accurate; instead, the site should be understood as an informal open-air recycling facility for various residual materials, with surprisingly well functioning logistics and an astonishing degree of ingenuity, but with extremely adverse impacts on the environment and human health.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Isaac Sarpong Awuah, waste management officer at Zoomlion Ghana Ltd., and George Sasuvi, scrap collector in Odorkor, Accra, for providing guidance at the site and contributing information for this article.

How to cite

Schwab, Oliver. “Onions and Tires in Sodom and Gomorrah.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2015), no. 21. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7378.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2015 Oliver Schwab

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Blacksmith Institute. The Worlds Worst 2013: The Top Ten Toxic Threats; Cleanup, Progress, and Ongoing Challenges. New York and Zurich: Blacksmith Institute and Green Cross Switzerland, 2013.

- Chama, M. A., E. F. Amankwa, and M. Oteng-Ababio. “Trace Metal Levels of the Odaw River Sediments at the Agbogbloshie E-waste Recycling Site.” Journal of Science and Technology (Ghana) 34, no. 1 (2014): 1–8. doi:10.4314/just.v34i1.1.

- Minter, Adam. “Continental Shift.” Scrap Magazine 72, no. 3 (2015): 78–94.

- Oteng-Ababio, Martin. “Electronic Waste Management in Ghana—Issues and Practices.” In Sustainable Development: Authoritative and Leading Edge Content for Environmental Management, edited by Sime Curkovic. InTech, 2012.