The construction of Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant began in 1973, and it was first put into use in 1979. Prior to its launch, three nuclear plants had been implemented in Switzerland: Beznau, Lucens, and Mühleberg. The addition of a cooling tower—clearly distinct from its surrounding landscape—set Gösgen apart from its predecessors. Furthermore, the construction of Gösgen coincided with a period of heightened engagement in the anti-nuclear movement within civil society.

Though the cooling tower is not a component of the nuclear reactor, the symbolic value inherent to its iconic visibility renders it representative of nuclear power itself—both for the currents of technological optimism spurring on the construction of the plants and for anti-nuclear countermobilizations. Thus, the cooling tower in Gösgen renders the unseen visible for the contending parties, symbolizing the possibilities and risks of atomic power.

The construction of Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant in 1976.

The construction of Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant in 1976.

Photograph by Jules Vogt, 1976.

Courtesy of ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Com_FC27-5013-045

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The architectural historian Thilo Hilpert has described the vast number of nuclear plants built during and following the 1950s as a global architecture; a trans-national dispersion of profanized cathedrals. Following Hilpert, a tension is revealed in the shaping of the nuclear plants: while existing as futuristic concrete domains, they simultaneously draw upon traditional architecture, notable in the towers and cupolas passed down from church architecture. Furthermore, the construction of Gösgen, like similar plants, embodied a demarcation from the surrounding picturesque scenery.

The distinction between nature and the power plant was manifestly articulated in regulations made in reference to the Natur- und Heimatschutzverordnung (Nature and Homeland Protection Regulations), deciding that the trees growing between the power plant buildings and the river Aare would be preserved to avoid a firm divide between nature and the industrial complex.

The distinction between the plant and the river Aare was not only aesthetic, but also served a utilitarian purpose. Unlike prior Swiss nuclear plants, Gösgen would not be allowed to discharge heated water into the river. Thus, despite the initial intention, the river water cooling system had to be abandoned in favor of a cooling tower; a construction originally developed for fossil-fueled power plants. Evoking the imagery of a profanized church tower, the 150-meter-tall tower and its rising vapors became visible from the neighboring towns and villages.

Unlike a church, however, the power plant emerged as a publicly inaccessible site perceived as disturbing the scenery through its towering presence. As noted by historian Patrick Kupper, concerns were in part articulated as demands for the cooling tower to be painted in order to camouflage its concrete structures, assimilating it into the surrounding landscape, though these were not met.

Protest mobilization against the construction of Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant, 27 June 1977.

Protest mobilization against the construction of Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant, 27 June 1977.

Blickpunkt vom 27.06.1977

® 1977 Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen SRF.

Click here to view original video.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Policemen in riot gear, 27 June 1.

Policemen in riot gear, 27 June 1.

Blickpunkt vom 27.06.1977

® 1977 Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen SRF.

Click here to view original video.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In much of the footage of the protests against the plant, the presence of the cooling tower serves as a backdrop, evoking ominous dystopian scenery. The anti-Gösgen movement culminated in two separate protests during the summer of 1977, the first drawing approximately 3,000 protesters and the second 6,000. In response, the authorities mobilized an unprecedented number of personnel, including 950 policemen from all Swiss cantons. As the protests grew in size, the methods of repression grew in intensity; initially using mainly tear gas and batons, the police and military personnel subsequently deployed rubber artillery to curb the protestors.

Despite drawing on established repertoires of contention from prior successful anti-nuclear mobilizations—notably those of Wyhl and Kaiseraugst—the protesters in Gösgen faced defeat, as the occupation failed and neither the construction nor implementation of the plant were halted. Perhaps, this failure can be attributed to the extensive counter-mobilization by the authorities, marking a novelty in the Swiss history of social movements.

Accessed via Flickr on 28 June 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Accessed via Flickr on 28 June 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Accessed via Flickr on 28 June 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

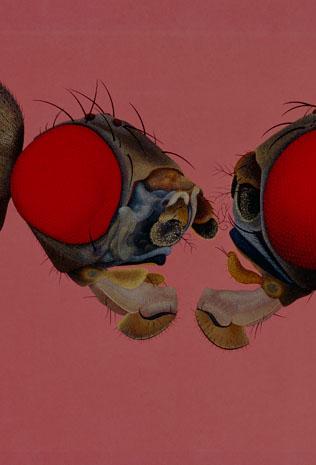

Illustrations of insect mutations by Cornelia Hesse-Honegger.

Though the protests subsided after 1977, the Gösgen plant was still the subject to critique after its opening, though less so in the form of collective action. Following the Chernobyl accident 1986, scientific illustrator Cornelia Hesse-Honegger began collecting insects nearby Swiss nuclear plants—including Gösgen—showcasing deformations presumed to be caused by low-level radiation. Illustrations of the insects were drawn to scale, displaying observed mutations.

In recent years, the critique of nuclear power as threatening nature—specifically the natural life of insects and, by extension, human life—has been reflected in the appearance of Gösgen’s nuclear power plant. In a collaboration between the power plant and a commercial light artist, the concrete structures of the plant were illuminated with stylized projections of Swiss flags, marine life, and, notably, insects. Photographs of these projections are routinely used for the commercial promotion of the power plant.

Illuminated projections of butterflies on the Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant, Kernkraftwerk Gösgen-Däniken AG. Projection by light artist Gerry Hofstetter.

Illuminated projections of butterflies on the Gösgen Nuclear Power Plant, Kernkraftwerk Gösgen-Däniken AG. Projection by light artist Gerry Hofstetter.

© Gerry Hofstetter

Beleuchtung durch Lichtkünstler Gerry Hofstetter

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

So, what can these visual motifs tell us about Gösgen? Mirroring Fredric Jameson’s description of postmodern architecture, the expression of the building is subordinated to the visual surface, to the “final decorative overlay.” The projections grant the plant a surface that reflects its outside world—in this case, the depiction of nuclear risk—in a subverted form. Butterfly motifs reminiscent of Hesse-Honegger’s illustrations (though here depicted in non-mutated forms) cover the concrete construction and illuminate its rising vapors. However, the existing critique is incorporated into the plant’s appearance without being confronted; rather it reflects a changing paradigm wherein nuclear power is increasingly regarded as a low-emission, climate-friendly energy source. The link between Gösgen and the natural world posited by the projected images notably diverges from the 1970s demands for a camouflaged power plant, which intended to hide it in nature. The initially antagonistic position of Gösgen against its surrounding natural landscape has now been exchanged for the image of thriving nature, literally and figuratively projected on the industrial complex.

How to cite

Siegrist, Hannah, and Nathan Siegrist. “Kernkraftwerk Gösgen: In the Towering Presence of Nuclear Power.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2020), no. 26. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9036.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Hannah Siegrist & Nathan Siegrist

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- “Das Kernkraftwerk Gösgen-Däniken.” Das Werk. Architektur und Kunst 63 (1976): 255–257.

- Hesse-Honegger, Cornelia. Die Macht der schwachen Strahlung: Was uns die Atomindustrie verschweigt. Solothurn: edition Zeitpunkt, 2016.

- Hesse-Honegger, Cornelia, and Peter Wallimann. “Malformation of True Bug (Heteroptera): A Phenotype Field Study on the Possible Influence of Artificial Low-Level Radioactivity.” Chemistry & Biodiversity, 5 (2008): 499–539.

- Hilpert, Thilo. “Kraftwerke der Strahlenden Stadt: Eine Skizze zur Architektur der Atomkraft.” In Century of Modernity: Das Jahrhundert der Moderne. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien, 2015.

- Häni, David. Kaiseraugst besetzt!: Die Bewegung gegen das Atomkraftwerk. Basel: Schwabe Verlag, 2018.

- Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review 146 (1984): 53–92.

- Kupper, Patrick. Atomenergie und gespaltene Gesellschaft. Die Geschichte des gescheiterten Projektes Kernkraftwerk Kaiseraugst. Zürich: Chronos, 2003.