In June 1930, a Soviet coast guard vessel attempting to apprehend a Japanese crabbing ship in the Sea of Okhotsk opened fire, killing one of the crew. The incident, one of several clashes between Soviet and Japanese vessels during the interwar era, was a product of long-standing tensions over the fisheries of the Russian Far East. However, this was not an instance of clashing commercial interests drawing their patron states into conflict, but rather a result of Russian nationalism and empire-building along the Pacific. Over the course of a half century, tsarist and Soviet governments went to great lengths to displace non-Russians from Far Eastern waters. They did so less for the economic value of the fisheries themselves as for the political significance of keeping “Russian” resources out of foreign hands.

A view of the Sea of Japan from Lazovsky Nature Reserve in Primorsky Krai

A view of the Sea of Japan from Lazovsky Nature Reserve in Primorsky Krai

Photo: Mark Sokolsky, 2012

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

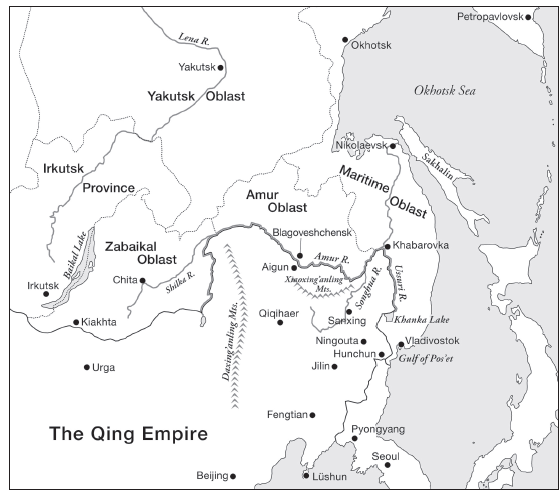

Russia’s Pacific fishing industry is a relatively recent phenomenon. In 1858–60, Russia acquired new territories from China along the Amur River and the Sea of Japan. The Russian and Ukrainian colonists who settled there fished in rivers and lakes but generally did not venture out onto the open sea. In contrast, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean fishermen were already active in what became Russian waters in the nineteenth century. Thousands of Chinese and Koreans came to the southern end of the Maritime Oblast to collect seaweed and sea cucumbers, while Japanese fishermen sought out salmon, crab, and herring.

Russian administrators were initially content to permit this activity, but by the 1880s many had begun to bristle at the depletion of “Russian” resources by foreigners, often casting the contest over marine resources in national or even racial terms. One senior Russian official warned that, with their knowledge of the coastline, foreign fishermen had become “masters of a Russian sea,” exhibiting the “malevolence of the yellow race toward Europeans.” Others blamed East Asians for ecological changes. Thus, in 1881, a naval liaison warned that exploitation by the Chinese threatened to cause the “complete destruction” of seaweed and salmon stocks. Another prominent observer, the Russian traveler Dmitry I. Schreider, faulted the Japanese and Chinese for “reckless embezzlement” of “those gifts which nature ha[d] so generously provided.”

In order to displace East Asians, beginning in the 1890s tsarist administrators attempted to create a Russian Far Eastern fishing industry from scratch. Resettlement officials offered land, equipment, and loans to would-be migrants with fishing experience, including many Balts and Finns. At the same time, administrators issued regulations designed to restrict the number of foreign workers in Russian waters and to limit certain fishing techniques and implements, particularly those favored by the Japanese, though such measures proved very difficult to enforce.

By the early 20th century, the rich fisheries of the Amur River estuary, the Tatar Strait, Sea of Okhotsk, and Sea of Japan became sites of competition between Russian/Soviet security personnel and Japanese fishers.

By the early 20th century, the rich fisheries of the Amur River estuary, the Tatar Strait, Sea of Okhotsk, and Sea of Japan became sites of competition between Russian/Soviet security personnel and Japanese fishers.

Credits: User Kmusser on Wikipedia. View image source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Nevertheless, by the early twentieth century foreign (primarily Japanese) fishermen were more numerous and better equipped than their Russian counterparts. Moreover, the Russo-Japanese Fisheries Convention of 1907, part of the treaty that ended the war of 1904–1905, granted Japanese fishermen wider access to Russian waters. In the wake of the treaty, Russian officials redoubled their efforts to settle fishermen in the Far East. They also began to focus on creating an industrial fishing fleet, which they believed could better compete with the Japanese. World War I and the upheaval following the revolutions of 1917, however, put this initiative on hold.

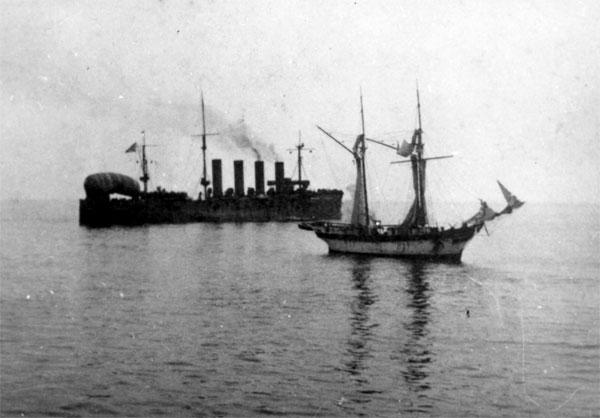

Enforcing fishing rights and boundaries was a constant problem for administrators of the Russian Far East. Here, the cruiser Rossiya detains a Japanese fishing schooner in Russian waters (1905).

Enforcing fishing rights and boundaries was a constant problem for administrators of the Russian Far East. Here, the cruiser Rossiya detains a Japanese fishing schooner in Russian waters (1905).

Click here to view Navsource source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

After coming to power in the Far East in 1922, Soviet authorities continued their predecessors’ efforts to displace foreign fishermen. The Soviet state invested heavily in the creation of large fishing conglomerates, purchased vessels abroad, manipulated the yen-ruble exchange rate to favor Russian fishermen, and imported settlers from the Baltic and Caspian regions. As during the tsarist era, conservation efforts were also highly politicized. Soviet vessels began to enforce anti-poaching laws with greater determination, resulting in violent clashes with Japanese fishermen that led to several fatalities and arrests. By the mid-1930s, as reported by Barbara Wertheim, Soviet fishing vessels outnumbered those of the Japanese in coastal waters, partly because the much larger Japanese ships had turned increasingly to pelagic fishing.

But by this time the decades-long effort to displace foreign fishermen had gained an increasingly destructive momentum. As a result of combined Soviet and Japanese fishing, the herring catch in Peter the Great Bay fell from 20,000 tons in 1926 to barely 180 tons ten years later. Humpback and chum salmon went into decline along Russia’s Sea of Japan coast, precipitating a temporary moratorium in 1945 on salmon fishing in the lower Amur River. Russian and Soviet efforts to break into Far Eastern fisheries were successful, but the survival of the industry had become less a geopolitical challenge than a complex ecological problem.

Archival sources for this contribution have been gathered at the State Archive of Primorsky Krai (F. 633, op. 7, d. 72, ll. 4-5 and F. 633, op. 5, d. 75, ll. 12-20), the Russian State Historical Archive (F. 391, op. 1, d. 1152, 186-68), and the Russian State Naval Archive (F. 410, op. 2, d. 4046, ll. 237-39, 245-47).

How to cite

Sokolsky, Mark. “Fishing for Empire: Settlement and Maritime Conflict in the Russian Far East.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2015), no. 20. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7330.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2015 Mark Sokolsky

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Aleksandrovskaia, L. V. “Osvoenie poberezh’ia Iuzhno-Ussuriiskogo kraia.” Zapiski Obshchestva izucheniia Amurskogo kraia, no. 30 (1996): 23–33.

- Barnes, Kathleen. “Fisheries, Mainstay of Soviet-Japanese Friction.” Far Eastern Survey 9, no. 7 (1940): 75–81.

- Mandrik, A. T. Istoriia rybnoi promyshlennosti rossiiskogo Dal’nego Vostoka (50-e gody XVII v. - 20-e gody XX v.). Vladivostok: Dal’nauka, 1994.

- Mandrik, A. T. Istoriia rybnoi promyshlennosti rossiiskogo Dal’nego Vostoka (1927-1940 gg.). Vladivostok: Dal’nauka, 2000.

- Shreider, D. I. Nash Dalʹnii Vostok (Tri goda v Ussuriiskom krae). St. Petersburg: A.F. Devrien, 1897

- Wertheim, Barbara. “The Russo-Japanese Fisheries Controversy.” Pacific Affairs 8, no. 2 (June 1935): 195–96.