Introduction

In 2015 the World Economic Forum declared water crises to be the biggest risk facing the planet. Since then, the combination of rapidly growing urban populations, insufficient or inappropriate infrastructure, and climate change has seen urban centers become increasingly vulnerable to water supply disruptions widely understood as “crises.” São Paulo, La Paz, and Cape Town are presented as cautionary tales to political and urban leaders in the expectation that this will lead to improved water planning and governance. Beyond these conspicuous examples, histories of urban water show that adverse events are commonly important drivers of change in water management—but patterns of crisis and response do not always produce good long-term outcomes.

In this exhibition, we invite visitors to consider the historical relationship of “water crises” of various kinds to the development of urban water systems, through the experience of the driest inhabited continent on earth, Australia. We have chosen a range of different departures from water-related business as usual—from shortage to flood, pollution to drainage—in the five mainland Australian state capitals from the late nineteenth century to the present. The part of this exhibition devoted to each city focuses thematically on just one or two kinds of crisis, while the timeline covers a wider range of events in each place.

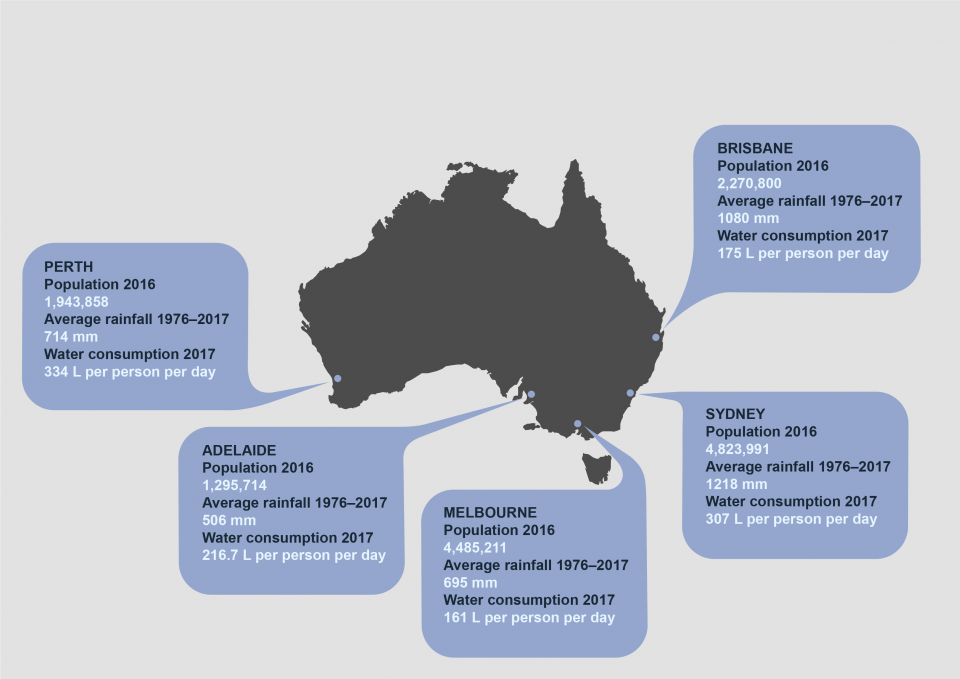

Map by Nathan Etherington.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Residents and water managers in each of these cities have had to adapt to different environmental conditions and constraints. Their climates vary considerably: subtropical Brisbane and Sydney are well-watered in most years; temperate Melbourne has a modest but evenly-distributed rainfall; Perth and Adelaide experience the wet winters and dry summers typical of Mediterranean climates. The eastern cities in particular are vulnerable to the effects of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which brings regular periods of savage drought, usually followed by a deluge of rain.

The amount of rain falling over each city and its catchment has varied over time, with the annual averages in each case lower—sometimes markedly—since 1975 than in the decades prior. Rainfall also varies—again, sometimes greatly—across each metropolitan area: for example, from 1961–90 an average of 1302 mm fell on Observatory Hill in central Sydney each year, but only 864 mm fell in average on Blacktown, a suburb of western Sydney.

Geography, too, is influential. Melbourne extends inland from the shores of an enclosed bay; Perth stretches along a sandy coastal plain dotted with wetlands and bounded by an escarpment; Sydney is oriented around its harbor as well as beaches and inland river systems; rivers also run through Perth, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Brisbane. Varying relationships between rainfall and surface water in the five cities give rise to different opportunities for water source development and waterborne waste disposal, as well as different water crises.

Brisbane is flooded by the second and third highest recorded floods within a fortnight. Unknown photographer, 1893.

Brisbane is flooded by the second and third highest recorded floods within a fortnight. Unknown photographer, 1893.

Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland. Image 84890. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

How a “crisis” is framed and understood matters: we need to ask how dominant understandings of adverse events emerge in particular contexts, and what responses and actors they summon. In Australia, when water supplies for a city have run low this has not been portrayed as a crisis of overconsumption, or of exceeding environmental constraints, but of insufficient supply and inadequate infrastructure. Almost invariably the immediate response has been to restrict water use in order to share remaining supplies, with the ultimate solution seen to lie in expanding capacity to extract or make more potable water—via dams, rivers, groundwater, or desalination. In the case of flooding, the crisis has not generally been discussed as one of poor urban planning creating flood vulnerability in particular areas, but rather as inadequate provision for floodwater control. Framing the problem in this way has summoned river engineers and dam builders, rather than more informed town planners and local governments. In the case of sewerage pollution on Sydney beaches, the problem was not seen as inappropriate waste of a resource or underinvestment in treatment but as poorly located disposal. This is not to say that the proposed solutions have not served the urban population well—at least in the short term they have worked to provide sufficient water, prevent flooding, and ameliorate disease and pollution. However, they have often also served to postpone vulnerability, rather than offering truly sustainable solutions.

Artist’s impression of the Warragamba Dam published with Sydney Water Board promotional material in 1957. Unknown illustrator, 1957.

Artist’s impression of the Warragamba Dam published with Sydney Water Board promotional material in 1957. Unknown illustrator, 1957.

Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The nature of responses has also been shaped by contemporary everyday politics. For example, for much of the twentieth century, heroic infrastructure was not only a means to address a specific water problem, but also a symbol of technological progress and environmental control, which drew admiring audiences (and voters) as well as expanding water supplies and in some cases providing capacity for flood mitigation. Historically, the most heroic infrastructure has been the large dams that ring every major city. More recently, desalination plants have taken on this mantle.

In Australia, primary responsibility for urban water supply and sanitation has lain with colonial and (after Federation of the colonies in 1901) state government. Administrative frameworks for the state management of water supply, sewerage and drainage have evolved in changing political and economic contexts, for example with the gradual rise and fall of engineer-led water Departments or Boards and the more recent transfer of services to water companies using publicly built infrastructure.

From the late nineteenth century, the construction and commissioning of centralized systems of water, sanitation, and drainage established an expectation among both water managers and urban residents that such services were the responsibility of a public authority. There were some exceptions—for example in what a reporter called Melbourne’s “heartbreak streets”—where suburban expansion outstripped government capacity for service provision. Here residents of postwar suburbs worked together to develop drained streets, and sanitation was often accomplished on-site with septic tanks; it took many years for government provision to catch up. In general, as the cities grew and the less costly opportunities for water supply and sanitation were exploited, water utilities have had to work hard to return some of the responsibility for water to system users, for example in encouraging water-conserving practices and the installation of water tanks and water-efficient appliances.

Children ride bicycles near the open drains of Bulli Street, Moorabbin, ca. the 1960s. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Children ride bicycles near the open drains of Bulli Street, Moorabbin, ca. the 1960s. Unknown photographer, n.d.

© City of Kingston.

Image courtesy of the City of Kingston Information and Library Service, L001717.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In Perth there was an early, unsuccessful experiment with private provision of the city’s water supply, which was mired in conflicts of interest and underinvestment; the government bought the system in 1896. All the urban water utilities were thereafter operated by government agencies for the public good. As water is foundational to human life and well-being politicians have not been bold enough to privatize urban water utilities outright, though the rise of neoliberalism has led to the corporatization of water in Melbourne (1992), Sydney (1994), Perth (1996) and Adelaide (2002).

Corporatization is essentially a soft form of neoliberal management, in which agencies are fully owned and operated by the state, but have a separate financial and legal status. This means that managers are expected to account for expenses and revenues as if the utility were an independent company, ostensibly separating political decision-making from the pursuit of economic efficiency. In some cases, management has been contracted out to private corporations. Citing reduced political interference and greater transparency and accountability, this institutional structure pushes questions of sustainability and long-term environmental impact to the margins, despite increasingly widespread public concern over environmental issues.

Many of the wetlands fed by the Gnangara groundwater mound are now in a state of ecological emergency. Photograph by Department of Water and Environmental Regulation, WA, 2010.

Many of the wetlands fed by the Gnangara groundwater mound are now in a state of ecological emergency. Photograph by Department of Water and Environmental Regulation, WA, 2010.

© 2010 Department of Water and Environmental Regulation, WA.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Problems with sewage treatment in Adelaide and the contamination of Sydney’s drinking water have been linked to cost-reduction programs at both utilities. Running water utilities as businesses can create perverse incentives, as the model generally relies on income from production and distribution of water, rather than its conservation. Water services managed for profit, as in the case of Sydney’s desalination plant, do not necessarily align with public or environmental needs. However, calls from the business sector for further privatization of Australian urban water services are ongoing, despite misgivings from many other quarters.

Water crises in the Australian past have mainly been associated with periods of rapid population growth, extreme weather events, or both. As we now proceed further into a period of global climate breakdown, the challenges to urban water systems will increase. History shows that many responses to past water crises have been reliant on construction of heroic infrastructure, which often provided opportunities for political gain, and which empowered engineers rather than citizens. This focus on engineering rather than social and cultural solutions has often deferred rather than solved problems. As the case studies here reveal, short-term solutions to water crises can come with a long-term cost. Past decisions to increase supply capacity and construct infrastructure can also limit future solutions. Urban sprawl; the loss of natural wet-lands and aquifers; and reliance on a single source of supply have long-term environmental consequences, as well as raising the cost of future responses. While the water-sensitive urban design movement is providing Australian water utilities with new strategies to meet the challenges of the future, questions remain around how to build a shared sense of responsibility for water security, and how to reconcile the demands of present profitability and future sustainability in urban water systems.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter